Intersectional STEM Network Formation for Underrepresented Students

Addressing the underrepresentation of women and people of color in STEM, this study explores the impact of peer networks on the persistence of underrepresented high school students of color in STEM at the postsecondary level. It delves into how race and gender intersect to influence the creation and maintenance of peer support networks and examines the compensatory role of longitudinal peer networks in forming local, intersectional networks in STEM.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Intersectional STEM Network Formation: Longitudinal Peer Support, Anti-Blackness, and Persistence in STEM for Underrepresented Students Frieda McAlear, Allison Scott, Alexis Martin, Sonia Koshy

Land Acknowledgement - Yanawana For the Coahuiltecan, this land is called Yanawana or Yanaguana (spirit water). Carried within this name is the creation story shared by the many peoples who claim central Texas as their ancestral territory, including the Coahuilteca, Tlaxcalteca, Comecrudo, Carrizo, Apache, and Comanche peoples. Other areas of Texas are home to the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas, the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, Anadarko, Arapaho, Biloxi, Caddo, Kiowa, Jumano, Karankawa, Tonkawa, Waco and Wichita. Indigenous Peoples of the Americas SIG We would like to start by honoring the elders, ancestors, and descendents of the Coahuiltecan as the tribe whose land we are colonizing at AERA.

Underrepresentation in STEM The underrepresentation of women and people of color in STEM throughout the education pipeline presents an opportunity to transform low-income communities and address what Gloria Ladson-Billings (2006) refers to as the education debt in the U.S. African Americans and Latinx comprise 30% of the population but just 16% of the STEM Bachelor s degree earners.

Research questions (1) Do the peer networks forged in a STEM program for underrepresented high school youth of color have an impact on their persistence in STEM at the postsecondary level? (2) Does the intersection of race and gender identities impact the creation and maintenance of peer support networks? (3) To what extent do distal but longitudinal peer networks compensate for the challenges in forming local, intersectional peer networks in STEM at the postsecondary level?

Theoretical frameworks: underrepresented peer networks in STEM and persistence Peer networks for students of color can supplement or supplant students family and education support systems, especially as these networks mitigate the barriers faced in post-secondary education (Grandy, 1998; Palmer et al, 2011; Rice & Alfred, 2014; Scott & Martin, 2014). Postsecondary peer support networks for underrepresented groups in STEM contribute to STEM persistence by: shaping self-efficacy within STEM (Figueroa, Hurtado & Wilkins, 2015); increasing the motivations of African American students in particular in STEM (Hurtado et al, 2009) and, bridging the receipt of academic support and social support (Palmer et al, 2011).

Theoretical frameworks: Intersectionality Intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) describes the ways in which those with multiple marginalized identities experience disproportionate levels of discrimination both between and within sub-groups. Intersectionality provides an explanatory theoretical framework for synthesizing the differential disparities in access to institutional resources for women of African descent and others with two or more marginalized identities (Crenshaw, 1993). Intersectionality illuminates differential barriers to STEM pursuit, including in (a) the creation and maintenance of peer networks; and (b) mediating persistence in STEM studies at the undergraduate level for underrepresented students of color.

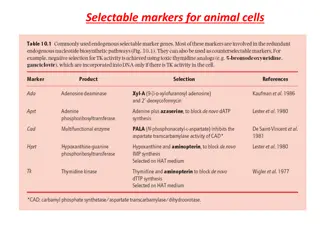

SMASH Program Overview and Alumni participants SMASH is a rigorous 5-week, three year residential STEM summer program for underrepresented youth of color at sites in California and Atlanta. Alumni participants (N=225): STEM majors: 72% Race/ethnicity: Latinx (51%), African-American (23%), multiracial (8%), Filipino (6%), and Vietnamese (5%), among others. Gender: female alumni (54%), male alumni (46%) Socioeconomic status: Low-income (63% Free and Reduced Price Lunch-eligible) and first generation college students (65%); 49% of program alumni are both.

Programming to develop peer networks at SMASH 5-week summer residential program in college/university dorms Cohort model of recruitment Community building activities (including communal dining) Small course size Leadership and public speaking skill development opportunities Role models, instructors, residential and site staff of color Networking skill development opportunities Social justice lens used in STEM course curricula

Study Instruments and Analysis Quantitative data: An online alumni survey provided data on student demographics, experiences and attitudes, current college majors, peer networks, and STEM persistence. Likert scale items used to assess peer networks: Peer network item: I feel strongly connected to at least one other SMASH alumni Peer influence on persisting in STEM from year to year (1=Strongly Disagree, 5=Strongly Agree) A university social fit scale: ( =.82) consisted of four Likert scale items such as I feel that this college/university is a good fit for me socially. Qualitative data: Program alumni focus group data (n=16) were collected in person over a series of small group discussions about college experiences, program impact, and emergent barriers to STEM persistence. Qualitative codes were assigned and analyzed to provide depth to the quantitative findings.

Findings Peer network formation and STEM persistence: related to persistence but not sufficient to overcome isolation in STEM majors. Participants majoring in STEM overwhelmingly reported having a close relationship to another program alumni (88%). University students who majored in STEM were significantly more likely to report that their peers from the high school program continued to influence their persistence in STEM from year to year (U=4384, p=.02), in comparison to their non-STEM peers. Of the women of African descent majoring in Computer Science, 29% reported leaving their degree programs due to the absence of peer and faculty social support.

Findings (continued) Intersectional peer network development, campus climate and anti-blackness: Racial differences in peer network formation: While there were no significant differences between male and female program alumni in peer networks formed (Z=-.679, p=.5), Latinx students (the largest racial/ethnic group in the sample) were significantly more likely to report a connection to another program alumni (Z=-2.421, p=.015) than their African-American peers. Racial difference in university climate: Program alumni of African descent were significantly more likely to report being differently treated because of their race/ethnicity in college (r=.217, p=.007). All program alumni majoring in STEM were significantly more likely to report being treated differently because of their race and gender, suggesting anti-blackness and sexism are more common in STEM major programs (gender: r=.217, p=.007; race/ethnicity: r=.202, p=.012).

Summary and Implications Peer network formation and STEM persistence This study demonstrated that goal-oriented peer networks formed in high school may supplement or supplant family and social networks in college/university for underrepresented students of color. Furthermore, evidence suggests that students of color who persist in STEM rely on these longitudinal networks to mitigate social isolation in their major programs. However, these peer networks may not be sufficient to mitigate the barriers to STEM persistence for underrepresented students of color with multiple marginalized identities, e.g. women of African descent.

Summary and Implications (continued) Anti-blackness and social isolation on campus and in STEM While gender was not significantly correlated with longitudinal peer network formation in this study, racial/ethnic identities were, suggesting that anti- blackness is a more salient factor in social isolation in college than sexism. Both STEM major programs and campus climates appear to present high barriers to inclusion for highly motivated students of African descent and women of color, suggesting these are critical sites for intervention.

Further reading Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241- 1299. doi:10.2307/1229039 Figueroa, T., Hurtado, S. & Wilkins, A. (2015). Black STEM Students and the Opportunity Structure. Paper presented at the Association for Institutional Research, Denver, CO. Grandy, J. (1998). Persistence in science of high-ability minority students. Journal of Higher Education, 69, 589-620. Hurtado, S., Cabrera, N. L., Lin, M. H., Arellano, L., & Espinosa, L. L. (2009). Diversifying science: Underrepresented students experiences in structured research programs. Research in Higher Education, 50, 189-214. Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). From the achievement gap to the education debt: Understanding achievement in US schools. Educational Researcher 35(7), 3-12. Martin, A. & Scott, A. (2014, May). Perceived Barriers and Endorsement of Stereotypes Among Adolescent Girls of Color in STEM. Presented at the annual conference of Alliance for Girls, San Francisco, CA. Palmer, R. T., Maramba, D. C., & Dancy, T. E.. (2011). A Qualitative Investigation of Factors Promoting the Retention and Persistence of Students of Color in STEM. The Journal of Negro Education, 80(4), 491 504. Rice, D., & Alfred, M. V. (2014). Personal and structural elements of support for African American female engineers. Journal of Stem Education: Innovation and Research, 15(2), 40-49. Sexton, J. (2012). Ante-Anti-Blackness: Afterthoughts. Lateral 1. Retrieved July 5, 2016, from http://lateral.culturalstudiesassociation.org/issue1/content/sexton.html

About Level Playing Field Institute Mission: Level Playing Field Institute is committed to eliminating the barriers faced by underrepresented people of color in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) and fostering their untapped talent for the advancement of our nation.

Thank you! Frieda McAlear, M.Res.: friedam@kaporcenter.org Allison Scott, Ph.D.: allison@kaporcenter.org Alexis Martin, Ph.D.: alexis@lpfi.org Sonia Koshy, Ph.D.: sonia@kaporcenter.org