Heilmeier Catechism for Successful Proposal Writing

The Heilmeier Catechism, a set of nine questions developed by George H. Heilmeier, is a vital tool for creating effective proposals. It emphasizes clear goals, hypothesis-driven research, avoiding jargon, and providing alternative plans. Incorporating the catechism in your proposal can enhance its quality and make it more compelling to reviewers.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

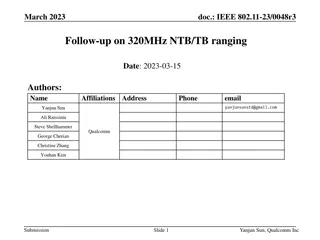

The Heilmeier catechism, as it became known among DARPA employees (and remainsan article of faithamong some DARPA program managers),consists of a series of nine questions. Heilmeier insisted that everyproposal to DARPA answer these nine questions. Everyone of your proposals should,too. For a briefbiographyof Heilmeier,see http://www.ieeeghn.org/wiki/index.php/George_H._Heilmeier. Heilmeier photo is courtesy of The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, and is used under theterms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version1.2.

Thinkingabout the questions is a great way to get started in writing yourproposal, the answers to the questions (particularly 7 & 8) will help you putnecessary boundary conditions on yourprojectbeforeyou get too far into the process, and incorporatingthe answers in yourproject narrative will help the reviewers positively assess yourproposal. For a briefbiographyof Heilmeier,see http://www.ieeeghn.org/wiki/index.php/George_H._Heilmeier. Heilmeier photo is courtesy of The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, and is used under theterms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version1.2.

Federalfundingagencies want to support hypothesisdrivenresearch. Instead of saying we will studythis process or we will measurex, state the overall goal of yourprojectin terms of a questionto be answered or an hypothesis to be tested. Make a distinction between goals (hypothesis to be tested) and objectives (intermediate steps along the path to answering the overarching question) and statethem both. NIH requires a specificaims section for everyproposal submittedto it. I think adoptinga specificaims section is a useful exercise for a proposer and reassures reviewers and program officers that you ve thoughtcarefullynot onlyaboutwhat you want to do (goal), butspecificallyhow you regoing to go aboutaccomplishing it (objectives). The no jargon rule is a good one. Not everybody who readsyourproposal (and decides its fate)may be an expertin yournarrow field. If you have to use jargon, explain yourterms. And never,ever use undefined acronyms. Ever.

Explicitly address this question in your background and introduction section. Cite freely.

Explicitly state why your approach is faster, better, cheaperdont rely on the reviewers to intuit it. Show how you ve tested yourapproachand its promise; provide preliminarydata. Discuss your Plan B. If yourapproachdoesn t work, what is youralternativeplan to save the project (and the fundingagency s investment)?

Is the problem importantto anybodybesides yourresearch group? Tell the programofficer and reviewers who benefits.

What will your successful project mean for your research? For the infrastructure of your institution and future capabilities? For your discipline? For related disciplines? For society? For the funding agency?? Will it create newknowledge? Trainthe next generation of scientists and engineers? Contributeto the nation s research infrastructure and technicalcapabilities? Solve an importantscientific, technological,or societal problem? Contributeto economic development? Whyshould a Congressman care?

Candidly discuss risks, butuse positive language.Donteversay a proposal is risky. (Fundingagencyemployees tendto be risk averse.) Speculative or promising or potentialhigh payoff is okay risky is the kiss of death.

Think not onlyof dollars, but of time and resources (personneland infrastructure). The program announcementwill often specify the maximum fundsthat can be requested. Typically, if you exceed that limit, yourproposal will be deemed non responsive and will be returnedwithoutreview. If the program announcementdoes not specify a budgetlimit, it will often indicate how much money has been allocated for the program and how many awards the agencyexpects to make. Use that information to set boundary conditions for your budget.

Read the program announcementcarefullyand be sure yourproposal fits the prescribedduration. A great additionto any proposal is a narrative or figural timeline for the project.

How are you going to evaluate the project as it proceeds, so that you know when to make mid course corrections? What metrics will youuse to evaluateprogress? How will you analyze and evaluateyourdata?How will you know when you re done ?

Put a section in the projectdescriptiontitledQualifications of Key Personnel and tellthe reviewers why you and yourteam are uniquely positionedto succeed. Describe yourexpertise and success in relatedwork. Mention the facilitiesyou have at yourdisposal and yourorganization sinstitutionalstrengths, including the availabilityof other experts to assist you. Not everyreviewer will look at the biosketches or the facilitiesdescription, butthey will read the project description.

Talk about opportunitycosts. Opportunitycost means what is the cost of not doing the project NOW? Whatwill be lost if the agencydecides Not this year. Maybenextyear. ?