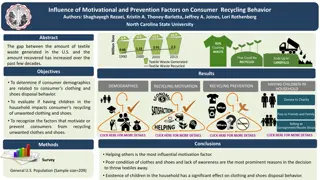

Coping with Rejection and Recycling Your Proposal Overview

Learn how to cope with rejection and recycle your proposal with expert advice from researchers in various fields. Understand the importance of learning from rejection, being prepared for multiple applications, and reevaluating your passion for your project. Discover tips on analyzing rejection, creating a flexible plan, and avoiding common mistakes in the proposal process.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Coping with Rejection AND RECYCLING YOUR PROPOSAL

Overview of the Session Part 1: Coping with Rejection (Alexandra) A few facts In our researchers own words : Elena Korosteleva (PolIR) Working out why the grant was rejected and what could have made it stronger In our researchers own words : Rob Fish (SAC) Part 2: Recycling your Proposal (Jacqueline) How to create a flexible plan In our researchers own words : Zaki Wahhaj (Economics) Common mistakes In our researchers own words: Markus Bindemann (Psychology) Questions

Coping with Rejection: Fact 1 You did your best, we know it. This is a learning opportunity. Even the most eminent scholars have lengthy negative CVs, and there s no shame in being unsuccessful, especially as success rates are so low. It s really difficult you ve got your team together, you ve been through the discussions and debates and the honing of your idea and then the grant writing, and then the disappointment of not getting funded. Focus less on the pain and see this as a chance to learn how to better prepare a proposal The pain can prevent you to think straight (analytically) for a while, so the sooner you move away from it, the better. We re not saying you shouldn t deal with the pain, but rather that engaging as soon as possible in the analyzing process will help you resolve that pain. The sooner is also the better as the process of analyzing the reasons for the rejection and forming a plan will be best if your memory is fresh. You do not want your research plans to completely go out of date!

Coping with Rejection: Fact 2 The role of luck, although difficult to discern, is important. While you need to learn from mistakes also consider that you might just be unlucky and need to apply regularly rejection is slightly less painful if you have other proposals under consideration by other funders This speaks in favor of planning a number of applications once your idea for one or multiple projects are formed Deep down, you know one won t be enough anyways! In this way, you re not waiting for the rejection(s) to come

Having said that A rejection might also be a good opportunity to step back from your project and really think about why you're doing it. Are you passionate about the project, or have you just got on the 'funding treadmill', believing you should be submitting funding bids without really thinking whether it's what you want. If you're just doing it through a sense of obligation it's actually 'hugely depressing' when you get the funding.

Coping with Rejection: Fact 3 Regardless of the pain and the learning, you need to make sensible decisions about whether, and how, to try again. You might want to recycle and resubmit because you feel passionate about your project, but this can make you blind to its shortcomings. A dose of tough love is needed for the recycling exercise! Understand that the priorities and mechanisms of funders are different from those of journals. What is publishable is not necessarily fundable. After analysis, you might come to the conclusion that it s best to move onto a new idea. For ex., you might conclude that the significance of your research question is just a bit too weak to be worth recycling. There s no shame in walking away.

Coping with Rejection: Fact 4 The more you deal with rejection, the easier it will become, i.e. the quicker you will be to move on and decide what to do with your rejected proposal See it as a skill to develop! You could call it resilience: to be successful, you need a degree of resilience to look for another funder or a new project, rather than embarking on a decade-long sulk, muttering plaintively about how the ESRC doesn t like your research whenever the topic of external funding is raised. You may find that you research suits a particular funder - there aren't that many to choose from, realistically. However, if your research doesn't fit any of the funders (and that happens), you may have a problem when it comes to funding vs publication. Having said that, we have seen academics who have had no funding for many years, suddenly win a big grant. But this involves multiple rejections along the way.

In our researchers own words Prof. Elena Korosteleva School of Politics and International Relations

Coping with Rejection: what is there to learn? Why your grant application was rejected How you could have made it stronger Salvage useful components Learn flexible planning: more on that later Get back on the horse

Working out why the grant was rejected If you are lucky enough to get feedback from the funder, you might get an idea. But this is not guaranteed: it can be difficult to understand from the feedback what the reasons for rejection were. Also, every batch of referees comments will contain at least one weird, wrong-headed, careless, or downright bizarre comment, and sometimes several. It often comes down to two reasons: The panel thought the research question wasn t important enough; winning grants is often a contest about significance, or The panel couldn t see how the project would answer the question Sometimes, a badly written grant just fails to convince the reader and they might not even know why Bear in mind though that funding rates are low and sometimes grants that propose well- designed projects answering key questions don t get funded because there just isn t enough money. However: Don t be too eager to assume that your grant was perfect. Most grants that don t get funded (and even some of those that get funded!) could be improved significantly.

Working out how you could have made it stronger Especially if it s unclear why your grant was rejected, you should look at what could be improved. You should mostly look separately at four elements: the description of the project, the background, the introduction and the summary. But you would do well to also consider the design as well as the writing. Does it fit the norms of the funders? What they fund rather than what is technically eligible (including budget)? And what about your track record?

Description of the project Is it clear what you will do? Have you explained the steps that will take you from starting research to having a set of findings that are written up and disseminated? Is the project divided into three or four (i.e. more than two and fewer than five) phases or work packages? Is it clear what will be discovered by each phase of the project?

Background to the project Have you given a good reason why you should do your project? Have you linked it to an important question? Is your link direct (your project will completely answer the question) or indirect (your project will take some important steps towards an answer to the question)? Has the funder stated explicitly or implicitly that this question is important? Have you linked the question clearly to each phase of your project by showing that we need to know what each phase of the project will discover? Do other authors agree with your specific we need to know statements or are they individual to you? Have you cited publications that demonstrate that your team are competent to produce new discoveries in this area? Have you overstated your contribution to the field? Could other people think this area is a backwater rather than a niche?

Introduction Does the introduction state every thing that we need to know . Does the introduction state every thing that the project will discover? Are these statements in the introduction clearly the same as the statements that begin the corresponding sub-sections of the background and the description of the project? They should be recognisably the same statements although they don t have to be exact copies.

Summary The summaries of most successful grant applications are appallingly bad. You can see this if you look for the details of successful proposals from the UKRI or from the ERC. However, a good summary helps the funding agency to choose more appropriate referees and it helps the referees and the committee members to understand the research. You should check the following:- Does the summary state every thing that we need to know . Does the summary state every thing that the project will discover? Are these statements in the summary clearly the same as those in the introduction? They should be recognisably stating the same thing without being exactly the same necessarily.

But more important than working out the reasons is perhaps to start salvaging what should be salvaged. Why? Because your motivation is likely to have decreased significantly at the news of the rejection. The sooner you start recycling, the better.

In our researchers own words Dr Rob Fish School of Anthropology and Conservation

PART 2 FLEXIBLE PLANNING TO AVOID DEAD END REJECTION OR AVOIDING THE SCRAMBLE TO RECYCLE A REJECTED PROPOSAL

Why plan flexibly rather than submit/recycle Rejection is inevitable even for excellent projects 1. Not all publishable research is fundable; don't assume that all worthwhile research can attract funding 2. Limited funding options for each discipline 3. Resubmission is not always an option 4. Deadlines may be annual and inconvenient 5. Funded projects take idiosyncratic forms - projects, fellowships, collaborative programme grants, consultancy, contract research 6. Much loved schemes are amended and scrapped 7.

Advantages of flexible funding plans The need to recycle is built into the plan it isn t an add-on You don t hit a dead end and waste an entire project - your research programme is never again hostage to one application You propose projects that have a chance with specific funders You can systematically plagiarise your previous funding bids You create efficiencies of scale and recycle individual components: questions, studies, methods, outcomes, ethics, justification, data management, GANTT charts Helps with time management You mitigate against bad luck

Our main recycling challenges Applicants are committed to one very specific and resource-intensive project proposal (partners/location/timing/participants) Applicants research is always dependent on a resource that funders do not allow or encourage, e.g. large sub-contracted survey Applicants research questions or methods are not valued/recognised/understood outside their sub-discipline, e.g. student samples, gaps in specific literatures Projects that fall uneasily between theoretical and applied research

Creating your plan: identifying constraints Track record Applied-theoretical Range of interests Discipline and methods Geography: local, national, international Working alone vs with others Type of resources required Amount of resource required (total value)

How short is your shortlist? Research Council? Leverhulme? British Academy/Royal Society? European Research Council/Horizon? Learned societies? National innovation funding? Special interest charitable funders? Industry and policy funders?

Other factors What funders do fund (rather than what they say they fund) Deadlines, decision times, panel meetings, starting dates Specific eligibility criteria for applicants, co-applicants and their projects Success rates Resubmission criteria (see later)

Shortlist-dependent tactics Targeting one or two funders with sequence of (related but not identical) projects in a similar field - create a research design portfolio of questions and studies that you can combine or split for different funders 1. Reframing projects to deliver theoretical/applied outcomes 2. Working collaboratively with a range of project partners and Co-Is to vary the focus of your projects place, people, methods, outcomes 3. Opportunistic approach: staying open to acting as Co-I on others projects, incoming fellowships, consultancy, networking grants 4.

In our researchers own words Dr Zaki Wahhaj School of Economics

ESRC: definition of resubmission Broadly the same title and/or proposal summary Overall aim of a new proposal and its high-level objectives broadly the same Broadly the same research questions Broadly the same resources required to carry out the research Principal and Co-Investigators on a proposal are amended (for example swapping of roles) whilst the content of the proposal is essentially the same. https://esrc.ukri.org/funding/guidance-for-applicants/resubmissions- policy/what-constitutes-a-new-proposal/

Leverhulme Trust: recycling policy The Trust is keen to avoid assuming the role of funder of last resort ; that is, of routinely providing support for proposals which have been fully matched to the requirement of another funding agency, but have failed to win support on the grounds of either lack of quality or Insufficient available funds ( unfunded alphas ). https://www.leverhulme.ac.uk/funding/our-approach-grant-making

Common planning mistakes Designing a project without reference to available funding Assuming publishable = fundable Committing to one very rigid design or collaboration Trying to bend the rules of every funding agency and proposing atypical projects Ulterior motives, e.g. wanting to help an individual or organisation A series of last-minute, thrown together applications with repeated mistakes

In our researchers own words Prof. Markus Bindemann School of Psychology

A final word before questions As you embark on the analysis of a rejection and start making plans for potential recycling, consult widely and honestly with your own team, DoR, senior colleagues and R&I officer(s)