Python Exceptions for Handling Runtime Problems

Exceptions in Python are essential for handling runtime problems and preventing programs from crashing unexpectedly. By using try-except blocks, developers can catch and manage exceptions that occur during program execution, ensuring smooth functioning. Learn how to effectively utilize exceptions to tackle errors and maintain program stability.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

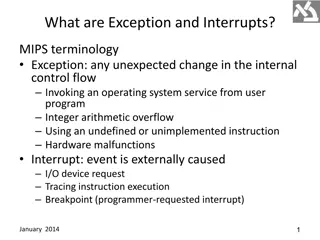

Problems Debugging is fine and dandy, but remember we divided problems into compile-time problems and runtime problems? Debugging only copes with the former. What about problems at runtime? To understand the framework for dealing with this, we need to understand Exceptions.

Exceptions When something goes wrong we don t want the program to crash. We want some way of doing something about it. When Python detects an problem, it generates an Exception object at that point in the running code which represents that problem. We can catch these and do something with them.

try-except If we suspect code might generate an exception, we can surround it with a try-except compound statement. Python terminates the execution where the exception is raised and jumps to the except block (no other code in the try block happens): import random try: a = 1/random.random() # Random generates number in # range 0,1 so # ZeroDivisionError possible except: a = 0 print("Done") However, this catches all and any exception, including those generated by ending the program normally or with the keyboard.

Try-except import random try: a = 1/random.random() # Random generates number in # range 0,1 so # ZeroDivisionError possible except ZeroDivisionError : a = 0 print("Done") One of the few examples of manifest typing in Python. For a list of built in exceptions, see: https://docs.python.org/3/library/exceptions.html#Exception If you want to catch a generic exception, catch Exception as this won't catch normal shutdown operations.

unhandled exceptions If the exception isn't handled, it moves to wherever the code was called from, and repeats this through each object and function. If there isn't a handler on the way, the code breaks and a stack back trace (or "stacktrace") and error message is printed. The stacktrace lists all the places the exception has bounced through.

If you want to catch all exceptions, catch the generic Exception. which encompasses most exceptions within its remit. This catches everything except SystemExit, which happens when a program ends, and KeyboardInterrupt, which happens when a user ends a program with CTRL-C or equivalent. If you want to catch all exceptions including these, catch BaseException. Excepts catch subclasses of the caught class, and not its superclasses, so a catch catches only more specific sub-exceptions.

Catch more than one error type simultaneously import random try: a = 1/random.random() except (ZeroDivisionError, SystemError) : a = 0 print("Done") Not that a SystemError is likely here!

Catch more than one error type alone import random try: a = 1/random.random() except ZeroDivisionError: a = 0 except SystemError: a = None print("Done")

User-defined exceptions The raise keyword, on its own inside a except clause, will raise the last exception. You can raise your own exceptions: a = random.random() if a == 0: raise ZeroDivisionError else: a = 1/a Or you can make your own types. We'll see how when we see how to make subclasses.

Making your own exceptions Use either Exception or one of the subclasses of BaseException as the base class for an exception class. The documentation suggests avoiding extending BaseException directly, presumably because it is too generic. Then: raise ExceptionClass This will generate a new object of that type, calling the zero-argument constructor. For other complexities, such as exception chaining and attaching stacktraces, see: https://docs.python.org/3/reference/simple_stmts.html#the-raise- statement

Interrogating the exception import random try: a = 1/random.random() except ZeroDivisionError: a = 0 except SystemError as se: print(se) print("Done")

Else If there's something that must happen only if exceptions aren't raised, put in a else clause: import random try: a = 1/random.random() except: a = 0 else: print(a) print("Done") # Exceptions here not caught.

Finally If there's something that absolutely must happen, put in a finally clause and Python will do its best to do it exception raised or not. import random try: a = 1/random.random() except: a = 0 finally: if a == None: a = -1 print("Done")

Finally details During this period, any exceptions are saved, to be re-raised after the finally. Finally clauses will always happen, even if there's a return beforehand. Exceptions in the finally clause are nested within the prior saved exception. Break and return statements within finally will delete the saved exception. If the try is in a loop, continue will execute the finally clause before restarting the loop, and break will execute the finally before leaving.

Exiting the system If you want to exit the system at any point, call: import sys sys.exit() This has an option: sys.exit(arg) Which is an error number to report to the system. Zero is usually regarded as exiting with no issues. For more on this, see: https://docs.python.org/3/library/sys.html#sys.exit See also errno, a special module on system error codes: https://docs.python.org/3/library/errno.html