Understanding Authorial Voice Construction Through Citations

Investigate the significance of authorial voice in academic writing and the challenge students face in understanding and incorporating it. Delve into the concept, construction, and implications of authorial voice, exploring its connection with citations and stance. Examine individual and social voice elements with examples to highlight their impact on text authenticity and authorial presence.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Designing a theoretical framework for investigating the construction of authorial voice through citations Dr. Qingyang Sun (Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University) Dr. Irena Kuzborska (University of York) Dr. Bill Soden (University of York)

OUTLINE The concept of authorial voice The construction of authorial voice Proposed framework to analyse authorial voice through citations Examples of analysing citation use in students writing Implications

WHY STUDYING AUTHORIAL VOICE? The construction of authorial voice is an important criterion for judging the success of students academic writing in many universities (Hyland, 2012; Hyland, 2004; Swales, 2004). However, students do not immediately understand what it means when we say we want to hear their voice in their writing (Hutchings, 2014, p.315)

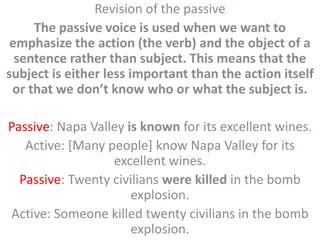

WHAT IS VOICE? Different explanations of voice (Hyland & Guinda, 2012). Hutchings (2014): Voice refers to the student s own views and to the ability to present other views as other voices (p. 315). Close connections between voice and stance

VOICE AND STANCE Hyland (2012, p. 134): stance refers to a writer s rhetorically expressed attitude to the propositions in a text voice as his or her attitude to a given community . Stance as an aspect of voice contributing to the construction of the writer s voice

INDIVIDUAL AND SOCIAL VOICE

INDIVIDUAL VOICE a writer s unique and recognizable imprint, associated with authenticity, resonance, authoritativeness, and authorial presence within a text (Tardy, 2012, p 37) autobiographical self (Clark & Ivani s, 1997) is made apparent by the inclusion of the writer s own life history, as well as experiences, values, and beliefs. (McKinley, 2017, p. 28)

SOCIAL VOICE The influence of social context in constructing voice related to self-representation and authorial presence but always taking into account the social worlds for and out of which a text is produced (Tardy, 2012, p 39)

VOICE AS DIALOGIC voice is neither controlled solely by writers nor determined by the social worlds within which they write it is subject to and result of both writer and social context (Tardy, 2012, p. 39) The key role of the reader in voice construction and the interaction between writers and readers and the resulting co- construction of voice at a particular time and space.

AUTHORIAL AND DISCOURSAL VOICE Clark and Ivani s (1997) three types of writer s textual identities: autobiographical self, authorial self and discoursal self. authorial self involves the textual evidence of writers feeling of authoritativeness and sense of themselves as authors. (Clark & Ivani , 1997, p.152) discoursal self constructed through the discourse characteristics of a text, which relate to values, beliefs and power relations in the social context in which they were written. (Ivani , 1998, p. 25) Issues of access, power, and interpersonal relations play a role in the author s construction of voice.

VOICE IN OUR STUDY The importance of both the authorial self and the discoursal self It is a writer s belief of themselves as authoritative and their active engagement with the voices of other writers as well as their ongoing negotiation of specific disciplinary conventions that are essential for successful academic communication. In line with recent research on expert writing (e.g., Groom, 2000a, 2000b; Hyland & Tse, 2005; Mansourizadeh & Ahmad, 2011) Issues of power and a sense of self or identity in a specific discourse community

THE CONSTRUCTION OF AUTHORIAL VOICE Through linguistic means: the lexical, syntactic, organizational, and even the material aspects of writing construct identity just as much as do the phonetic and prosodic aspects of speech, and thus writing always conveys a representation of the self of the writer. (Ivani & Camps, 2001, p. 3) Through citation forms: integral,author-prominent citation non-integral,information-prominent citation Through reporting verbs: indicating writer s stance towards the content from the source Through citations

SOME BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY Aims To examine students rhetorical purposes for source use over time, while also comparing source use by academic score with a focus on the extent to which students acknowledge other sources and evaluate them Study participants Ten Chinese master s students of TESOL in a UK university with an overall IELTS score of above 7 aged from 22 to 27 Data collection and analysis Students course assignments and their dissertation literature review chapters Petric s (2007, pp.243-246) adapted rhetorical functions of citations framework Discourse-based interviews with students

DESIGNING AN INTEGRATED FRAMEWORK Petric ,2007 Function explanation example Attributio n to attribute information or activity to an author According to feminist film critic Laura Mulvey s (1975) analysis of the gaze, in binary looking relations men tend to assume the active role of a looking subject while . Exemplific ation usually preceded by for example or e.g., provides information on the source(s) illustrating the writer s statement. Many feminist scholars debate the concept of woman and gender categories as such. Monique Wittig, for example, argues that woman is defined only in relation to man, Further reference usually preceded by see, refers to works providing further information on the issue See Trafficking in Women and Prostitution in the Baltic States: Social and Legal Aspects (IOM, Finland, 2001). Statement of use to state what works are used in the thesis and for what purposes In further analysis I will rely on Rosemary Henessy s (1998) theorization of how queer visibility can be appropriated for commodity purposes. Applicatio n makes connections between the cited and the writer s work Having been in contact with high school life helps formulate interview questions in the language of the interviewee now that I became a retrospective researcher (Reinhartz, 1992, p. 27). Evaluation the work of another author is evaluated by the use of evaluative language ranging from individual words (e.g., evaluative adverbs) to clauses expressing evaluation. Elizabeth Grosz s concept of the body as inscriptive surface is an ingenious way out of the nature/culture impasse.;The main flaw with Gray s analysis is that she omits to take into account the very slippery nature of language and in that respect of jokes. Establishin g links between sources to point to links, usually comparison and contrast,between or among different sources used While Rich argues that men enforce compulsory heterosexuality upon women, Suzanne Pharr claims that both homosexual women and men are perceived as a threat to the normative heterosexual patriarchal order, which is characterized by male dominance and control. Comparison of one s own findings or interpretation with other sources This type of citation is used to indicate similarities or differences between one s own work and the works of other authors, typically when discussing the findings.

OUR ADAPTED FRAMEWORK Citation Category Sub- category Explanation Example from students texts Simply acknowledging the source; no other citation functions can be recognised. English native speakers often use lexico-semantic, syntactic and acoustic-phonetic information to help them segment speech in daily life (Sanders and Neville, 2000). Attribution - , research has been conducted to seek its underlying factors using factor analysis (Aida, 1994; Liu and Jackson, 2008; Mak, 2011; Park, 2014). Generalisat ion Making a generalisation from multiple sources. MacIntyre (1999) defined FLA in general as Young (1992) expressed FLA as Both of their definitions regard FLA as a distinct kind of anxiety specific to foreign language learning Compare/ Contrast Links between sources Highlighting the similarity or difference between sources. Exemplifica tion/ further reference Using a source as an example of a larger body of literature. FLA could play a positive role in Second Language Anxiety. For example, Park and French s (2013) study showed that Evaluating a proposition positively, using positive evaluative expressions; e.g., demonstrate, point out, usefully, reasonable. Reppen (2010) pointed out that the corpus allowed language learners to master the knowledge deeper and longer as they manipulate language when using the corpus. Positive evaluation Evaluation Evaluating a proposition negatively, using negative evaluative expressions; e.g., neglected, biased. Lip (2009) focuses on different reasons for uses of VLSs. However, its interview questions are too specific, which might be misleading. Negative evaluation

EXAMPLE OF STUDENT TEXT 1.1 The selection of materials for effective oral pedagogy The first part of this section will be devoted to discussing the appropriate materials for oral instruction with respect to the authenticity and chosen models in the second and foreign language classrooms. As Burns (1998) notes, authentic materials in the second and foreign language classrooms are normally hard to find since many English Language Teaching (ELT) materials are served to achieve certain pre-determined pedagogic goals instead of reflecting the natural functional language use. She further offers various specific problems. For instance, pre-scripted dialogues appearing on the textbooks tend to be short and grammatically perfect. For turn-taking, one person has to wait until the other interlocutor has finished, which is not likely happening in real life because overlaps between two speakers are quite common. McCarthy and O'Keeffe (2004) also express the same concern over the pre-scripted dialogues employed for classroom use and propose that they may not help to equip learners with essential conversational skills outside of the classroom. In addition, Burns (2001) and Carter (1998) both point out that some crucial language features may be omitted in the dialogues on textbooks. To illustrate, discourse markers and hedges are rarely found and responses to questions are largely rigid and fixed. It seems that there is an urgent need to seeking authentic materials for classroom use. Nevertheless, Cook (1998) argues that second and foreign learners may not need to pursue native-like language in that they do not possess enough time as native children. Furthermore, native-like English entails a wealth of idiomatic expressions, which might not be frequently used among foreign language learners. Based on those opposed concerns, it is clear that the problem lies with the degree to which authenticity of the materials should pursue. (Elsa, Term2)

EXAMPLE OF STUDENT TEXT 1.1 The selection of materials for effective oral pedagogy The first part of this section will be devoted to discussing the appropriate materials for oral instruction with respect to the authenticity and chosen models in the second and foreign language classrooms. As Burns (1998) notes, authentic materials in the second and foreign language classrooms are normally hard to find since many English Language Teaching (ELT) materials are served to achieve certain pre-determined pedagogic goals instead of reflecting the natural functional language use. She further offers various specific problems. For instance, pre-scripted dialogues appearing on the textbooks tend to be short and grammatically perfect. For turn-taking, one person has to wait until the other interlocutor has finished, which is not likely happening in real life because overlaps between two speakers are quite common. McCarthy and O'Keeffe (2004) also express the same concern over the pre-scripted dialogues employed for classroom use and propose that they may not help to equip learners with essential conversational skills outside of the classroom. In addition, Burns (2001) and Carter (1998) both point out that some crucial language features may be omitted in the dialogues on textbooks. To illustrate, discourse markers and hedges are rarely found and responses to questions are largely rigid and fixed. It seems that there is an urgent need to seeking authentic materials for classroom use. Nevertheless, Cook (1998) argues that second and foreign learners may not need to pursue native-like language in that they do not possess enough time as native children. Furthermore, native-like English entails a wealth of idiomatic expressions, which might not be frequently used among foreign language learners. Based on those opposed concerns, it is clear that the problem lies with the degree to which authenticity of the materials should pursue. Attribution Compare/ Contrast Compare/ Contrast Attribution (Elsa, Term2)

EXAMPLE OF STUDENT TEXT Nowadays, educational technology is widely used in many fields and is consist of various tools, such as teaching and learning management system (Meiloudi, 2015; Ravichandran, 2000; Abdullah, 2014), computers Generalisation and related multimedia devices (Hofstetter, 2001; Mohamad, 2012), mobile learning devices (Kelly and Minges, 2012; Graham, 2013), instant messengers (Bossa, Stevens and Tawel, 2012), the Internet (Grace & Kenny, 2003; Paramskas, 1993) and interactive whiteboard (Davis, 2007; Brozek & Duckworth, 2013), etc. (Isabel LR) merely grouped superficially by the type of technology they focused on no evidence of Isabel s understanding of any content of these sources, apart from perhaps a reading of the titles

EXAMPLE OF STUDENT TEXT A study conducted on sixty Spanish students at intermediate levels in Wheaton College showed that the error corrections written feedback neither helped avoid surface-level errors nor improved to a significant extent L2 learners level of writing (Kepner, 1991). But this experiment failed to consider other forms of feedback which may play a positive role in the production of higher-level writing. (Fiona T1) Evaluation (negative)

SUMMARY In our study, we defined the construction of voice as a writer s attempts to persuade readers [tutors] of their ideas while simultaneously trying to express their self-presence and align with other contributors and with a broader community of practice. We acknowledge though that the construction of voice exerts an effect on the reader and can reveal a different writer identity at a different time and place (or not reveal an authentic writer identity). Writers are engaged in a continuous process of self-fashioning, using language to perform identities that will change to meet the demands of different contexts, genres and audiences (Cameron, 2012, p. 253) In the case of our students, they can do their best to adopt a community voice and present themselves as competent individuals in line with the expectations of their community members (i.e., tutors). However, by doing this, students could be suppressing their own social and cultural identities. It is therefore crucial that when investigating students citation practices, we also hear their explanations for their specific citation uses.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHING Teach the concept of authorial voice through analysing rhetorical functions of citations framework Demonstrate successful and unsuccessful excerpts of student texts together with analysis of the citation types used Focus on overall rhetorical effects of the passage, which is then further broken down into each citation function However, teachers should not only encourage students to reflect on different meanings, clarify consequences of inappropriate citation use, but also support them in asserting their identity, their distinctiveness.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH Rhetorical functions of citations need to be analysed through global understanding of the citation within its context Analysis of citation functions needs both the researcher s interpretation and the writers confirmation Future: Can corpus linguistics methods in analysing citation use be used to inform researchers interpretation of texts? Can we move beyond manual coding of citations?

REFERENCES Cameron, D. (2012). Epilogue. In K. Hyland & C. S. Guinda (Eds.), Stance and voice in written academic genres (pp. 249-256). Palgrave Macmillan. Clark, R., & Ivani , R. (1997). The politics of writing. New York: Routledge. Groom, N. (2000a). A workable balance: self and source in argumentative writing. In S. Mitchell & R. Andrews (Eds.), Learning to argue in higher education (pp. 65 145). Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook Heinemann. Groom, N. (2000b). Attribution and averral revisited: three perspectives on manifest intertextuality in academic writing. In P. Thompson (Ed.), Patterns and Perspectives: Insights into EAP writing practice (pp. 14-25). Centre for Applied Language Studies, Reading. Hutchings, C. (2014). Referencing and identity, voice and agency: adult learners' transformations within literacy practices. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(2), 312-324. DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2013.832159 Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary discourses. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. Hyland, K. (2012). Undergraduate understandings: Stance and voice in final year reports. In K. Hyland & C. S. Guinda (Eds.), Stance and voice in written academic genres (pp. 134-150). Palgrave Macmillan. Hyland, K. & Guinda, C. S. (2012). Stance and Voice in Written Academic Genres. Palgrave Macmillan. Hyland, K., & Tse, P. (2005). Hooking the reader: A corpus study of evaluative that in abstracts. English for Specific Purposes, 24(2), 123 139.

REFERENCES (2) Ivani , R. (1998). Writing and identity: the discoursal construction of identity in academic writing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. Ivani , R. & Camps, D. (2001). I am how I sound: Voice as self-representation in L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 10(1-2), 3-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060- 3743(01)00034-0 McKinley, J. (2018). Integrating appraisal theory with possible selves in understanding university EFL writing. System, 78, 27-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.07.002 Mansourizadeh, K., & Ahmad, U. K. (2011). Citation practices among non-native expert and novice scientific writers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(3), 152 161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.03.004 Matsuda, P. K. (2011). Conceptions of voice in writing assessment rubrics. Paper presented at the American Association for Applied Linguistics. Chicago, III. Matsuda, P. K. (2001, April). Voice in Japanese written discourse. Journal of Second Language Writing, 10(1 2), 35 53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060- 3743(00)00036-9 Petric , B. (2007). Rhetorical functions of citations in high- and low-rated master s theses. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 6(3), 238 253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2007.09.002 Swales, J. (2004). Research genres. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tardy, C. M. (2012). Current conceptions of voice. In K. Hyland & C. S. Guinda (Eds.), Stance and voice in written academic genres (pp. 34-48). Palgrave Macmillan.

THANK YOU! DR. QINGYANG SUN qingyang.sun@xjtlu.edu.cn DR. IRENA KUZBORSKA irena.kuzborska@york.ac.uk DR. BILL SODEN bill.sodden@york.ac.uk