Discrediting Dunning: The Untold Story of Reconstruction by W.E.B. Du Bois

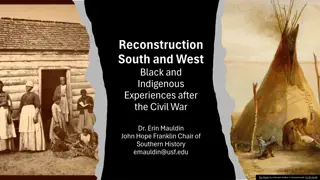

Reconstruction after the Civil War marked a pivotal period in U.S. history, with the promise of progress towards multiracial democracy curtailed by resistance and the rise of the Jim Crow Era. William Archibald Dunning's influential narrative upholding segregation was challenged by W.E.B. Du Bois, shedding new light on this critical chapter in American history.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Du BOIS DISCREDITS DUNNING: RE-WRITING the HISTORY of RECONSTRUCTION William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963) Niagara Delegate Meeting, Harpers Ferry, W VA, 1907 W.E.B. DuBois Collection; University of Massachusetts W. E. Burghardt Du Bois Black Reconstruction First Edition cover, 1935 By Steven S. Berizzi Professor, History & Political Science Norwalk Community College

Reconstruction 1865-1877 Reconstruction, an important era in United States history, arguably began on January 1, 1863, in the middle of the Civil War, when President Abraham Lincoln issued his final Emancipation Proclamation, in which he purported to free many, but not all, of nearly 4,000,000 enslaved people in 15 states. After the end of the War, three amendments to the U.S. Constitution were passed by Congress and ratified by the existing states. 1865: The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in all states. 1868: The Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed the equal protection of the laws. 1870: The Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed voting rights for Black men. These constitutional amendments, and equally important, the statutes passed by Congress to enforce them, were the essence of the Second American Revolution of Reconstruction. Black Americans and their political allies had great hope that the nation would progress towards a multiracial democracy.

Origin of the Jim Crow Era Their great hope for a multiracial democracy proved to be short-lived. Resistance to Reconstruction reforms began almost immediately and often was violent. White supremacist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan used terroristic tactics to intimidate Black Americans. Political barriers to political participation were raised by southern and northern White Democrats, both of whom had opposed President Lincoln s policies throughout the Civil War. By the early 1870s, the political tides were turning against Reconstruction. All former states of the Confederacy were eventually redeemed, thereby restoring the control of state governments to conservative White Democrats. The redeemers drove Black officeholders from office, restricted the voting rights of Black men, and passed laws to segregate transportation, schools, and public accommodations. This became known as the Jim Crow Era.

William Archibald Dunning The necessity of segregation was justified by a widespread belief that Reconstruction s impulse for reform had been a failure, and was properly ended with the so-called Bargain of 1877, which resulted in removal of the remaining federal troops from the South. The absence of in-person daily federal oversight allowed the redeemers to expand their legal repression of Black Americans and control their labor. Slavery was not re-established, per se, but the effects of redeemers expansion of legally-sanctioned repression came close to mirroring the effects of slavery. By 1900, William Archibald Dunning, a history professor at Columbia University, was training a generation of scholars, providing them an intellectual defense for ending Reconstruction and rationalization for the passage of myriad Jim Crow laws. Dunning s influence on the American political and intellectual landscape was enormous; for at least thirty years, the Dunning School dominated Reconstruction studies.

Dunnings Reconstruction Professor Dunning wrote prolifically; it would be difficult to summarize his ideas in a brief presentation. However, a few of his main points merit attention. First, during Reconstruction, when Black men were permitted to vote and hold office, they exercised an influence in political affairs out of all relation to their intelligence or property. Second, the primary goal of the redeemers was the resumption of white government in the South. Third, Dunning conceded that the Ku Klux Klan s frequent use of violence was to some extent the expression of a purpose not to submit to the political domination of the blacks. Dunning s perspective about Reconstruction might be summarized as the following: Black men were given too much political power during Reconstruction; White men were determined to end what they perceived to be an era of Black rule; White redeemers and their political allies were willing to use violence, even terrorism, to return the nation to its pre-War political status quo, founded on White supremacy.

Dunnings Influence In 1907, after four years of work, Professor Dunning published Reconstruction, Political and Economic, 1865-1877, the second volume in his ambitious study of the controversial period that older Americans still remembered. In the early decades of the 20thcentury, Columbia s history department was often considered pre-eminent. That contributed to Dunning s outsized influence. Dunning died 100 years ago, but one recent neo-Dunningite succinctly expressed Dunning s thesis: Reconstruction was bad, objectively bad. Others have been even more un-generous, referring to Reconstruction s bold experiment to a create a multiracial democracy, as a travesty, essentially the product of the federal government s overreach. That interpretation has considerable appeal in today s political climate.

Dunnings Reconstruction from Academe to Popular Culture: D.W. Griffith s The Birth of a Nation According to Professor Eric Foner, who will be discussed in greater depth later in this presentation, a widespread popular audience imbibed [the Dunning School s] representation of history in D. W. Griffith s film The Birth of a Nation (1915), which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and presented blacks as uncivilized savages. Over 100 years later, the racist perspective conveyed in this classic film is shocking, but it appealed to the prejudices of many early-20th century White Americans. After a screening of the film at the White House, President Woodrow Wilson, a Virginia native, lawyer, and professional historian, reportedly remarked: It's like writing history with lightning. My only regret is that it is all so terribly true.

W.E.B. Du Bois: Scholar and Activist Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, about 70 miles north of Norwalk, in 1868, during Reconstruction, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was the first Black person to earn a Ph.D. in history from Harvard University, after which he became the foremost Black intellectual of his time. In 1900, Du Bois presciently asserted that, the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line. That insight was indicative of Du Bois s towering, versatile intellect. He taught at several Historically Black Colleges and Universities and was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, for decades the best-known civil rights organization in the nation. David Levering Lewis, a historian at New York University, and earlier at Rutgers University, who won Pulitzer Prizes for both volumes of his authoritative biography of Du Bois, described DuBois s many accomplishments as a fabulous life.

Du Boiss Masterpiece: Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880 According to Reconstruction scholar Eric Foner, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860 1880 is a complex, frustrating, but indispensable book. Its analysis is highly sophisticated, and its language often approaches the poetic. One brief example: toward the end of his book, Dr. Du Bois lamented, The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery. At a time when the Dunning School of Reconstruction historiography was dominant, Du Bois challenged Dunning s racist conventional wisdom, arguing that Reconstruction was, at worst, a noble failure, a failure especially important to Black Americans who had fought to free themselves during the Civil War.

More about Black Reconstruction in America Some of Dr. Du Bois s claims were highly controversial. For example, DuBois s analysis begins with a discussion of enslaved peoples wartime resistance to plantation and farm labor, which DuBois asserted constituted a general strike in which workers ceased all economic activity as a tactic for forcing improvements in wages and working conditions. During the War, according to DuBois, resistance to slavery transformed itself: from a problem of abandoned plantations and slaves captured while being used by the [Southern] enemy for military purposes; the movement became a general strike against the slave system on the part of all who could find opportunity. The trickling streams of fugitives swelled to a flood. Once begun, the general strike of black and white went madly and relentlessly on like some great saga.

Controversy For decades, the Dunning School dominated the study of the post-Civil War Era. In contrast, Dr. Du Bois s Black Reconstruction was considered an outlier and a curiosity, which attempted to apply Marxian class analysis to distinctly American events. Even some Black commentators in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s were skeptical about Du Bois s increasingly radical ideas. Suspected of disloyalty to the United States, Du Bois was surveilled for many years by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In 1951, Du Bois was indicted, arrested, and arraigned in federal court, accused of being an agent of the Soviet Union because he had circulated a petition protesting nuclear weapons. Du Bois was acquitted but the experience embittered him. In 1961, as he neared the end of his life, he applied for membership in the Communist Party USA, renounced his citizenship, and moved to Accra, Ghana, in West Africa.

Reconstruction Historiography in the Civil Rights Era According to Hannah Rosen, a Reconstruction specialist at the College of William and Mary: Jim Crow was the inevitable product of enduring prejudice. Such ideas reflect a presumption of a crippling black powerlessness vis- -vis white racism that many students believe persisted until at least the civil rights era of the 1960s. In fact, Black men and women were active agents of change. Prompted by the growing consciousness of social justice advocated by the Civil Rights movement, the scholarly tide began to turn against the Dunning School. In 1965, Kenneth Stampp, a historian at the University of California, Berkeley, published The Era of Reconstruction, 1865-1877, which provided a direct assault on Dunning s old ideas. It was the first of many revisionist studies.

Du Bois at 100 years: 1968 Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. s speech Shortly before his assassination, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave a speech titled Honoring Dr. Du Bois, in which he praised both Du Bois s scholarship and activism. According to Dr. King, Dr. Du Bois: realized that studies would never adequately be pursued nor changes realized without the mass involvement of Negroes. The scholar then became an organizer and with others founded the NAACP. At the same time, he became aware that the expansion of imperialism was a threat to the emergence of Africa. Du Bois was a legendary public intellectual, who genuinely distinguished himself in both facets of his vocation. Posterity recognizes him as scholar and activist second to none.

Dr. King and the Dunning School: Had Dr. King read Dunning s work? Toward the end of his tribute to the author of Black Reconstruction, Dr. King advised, it would be well to remind white America of its debt to Dr. Du Bois. When they corrupted Negro history they distorted American history, because Negroes are too big a part of the building of this nation to be written out of it without destroying scientific history. White America, drenched with lies about Negroes, has lived too long in a fog of ignorance. Dr. Du Bois gave them a gift of truth for which they should eternally be indebted to him. Dr. King did not mention, by name, William Archibald Dunning, but his expression of gratitude for Du Bois clearly repudiated the Dunning School, as well as its many falsehoods and distortions of Reconstruction history. Dr. Martin Luther King honored Dr. Du Bois Carnegie Hall; February 23, 1968 100thAnniversary of Du Bois s birthday

Eric Foners Revisionism Eric Foner is the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History Emeritus, at Columbia University. One of the highlights of his long career was receiving the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in History. His Reconstruction: An Unfinished Revolution, 1863- 1877, published in 1988 (updated in 2014), is generally regarded as the authoritative study of Reconstruction and its controversies. William Archibald Dunning s tenure at Columbia University preceded Professor Foner s by several decades. Regarding history taught by the Dunning School, Foner is succinct: the Dunning School was part of the edifice of the Jim Crow South; it was part of real life, not just a historical point of view. It was an intellectual justification for the disfranchisement of African Americans and helped to legitimize the deep resistance to change in the South of the first fifty to sixty years of the twentieth century.

Foners Assessment of Du Bois According to Professor Foner, Du Bois: long sought to counteract the Dunning School interpretation, which he saw as a severe impediment to any hope for improvement in the condition of blacks in twentieth-century America. Reconstruction had been a brief moment when blacks enjoyed the basic rights of citizenship, rights that he long struggled to see restored. For him, the era was tragic not because it was attempted but because it failed. As early as 1903, Du Bois included in The Souls of Black Folk sympathetic accounts of the Freedmen s Bureau and of Northern teachers who ventured south to teach the freedmen after the Civil War. In Foner s discerning view, eight decades after its publication, Du Bois s Black Reconstruction remains one of the landmarks of US historical scholarship. In contrast, Dunning s books and articles, while well known to specialists, are otherwise ignored, consigned to the ash heap of history.

Other Perspectives Few eras in United States history remain more vigorously contested than Reconstruction, and W.E.B. Du Bois is often found is at the center of the controversy. To some, he was a brilliant, pioneering scholar, denied his rightful place in the academic professions by deep racism. To others, he was a dangerous leftist who sought to weaponize Reconstruction historiography. Martha Jones, professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, explained: Black Reconstruction, published against a backdrop of violence and segregation, met with a vitriolic reception. White writers leveled sharp- tongued critiques. Black journalists assessed the work favorably but with reservations. Despite the early criticism, over time Black Reconstruction came to be recognized as a towering analysis of American culture and an important work of history.

A Great and Difficult Man W.E.B. DuBois died in Accra, Ghana, in West Africa, where he lived in self-imposed exile, on August 27, 1963, one day before the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. shared the news of his passing with the vast audience at the March. In his 1993 30-year retrospective on Du Bois, historian and Professor Waldo Martin (University of California, Berkeley) described him as a great and difficult man. Both qualities were displayed in Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880. Du Bois s landmark book demonstrated his greatness, in its fierce determination to challenge the perspective of Reconstruction taught in the Dunning School. His difficulty lay in his insistence on looking at the post-Civil War era from an unpopular Marxian perspective. Nonetheless, Dr. Du Bois was a model scholar and activist. W. E. B. Du Bois, receiving an honorary degree from the University of Ghana, on his 95th birthday, February 23, 1963. Du Bois Collection, University of Massachusetts

Concluding Thoughts My students occasionally assert that history never changes. The fact is that the recording, writing and interpretation of history changes or is updated constantly. William Archibald Dunning was a serious scholar at a great university, a well-regarded teacher, and the influential creator of a narrative of Reconstruction. But he was also a product of his time ,who came of age as Reconstruction was ending, when white supremacy was pervasive. Dunning s books and articles in the early 20th century set the tone for the study of Reconstruction for at least two generations, and the tone he set was rife with racism. In the 1930s, W.E.B. Du Bois, an even greater scholar than Dunning, courageously challenged Dunning s interpretation of Reconstruction. The original reception to Du Bois was both skeptical and critical, but Du Bois persisted in his effort to set the historical record straight. Almost 90 years later, we know now that Du Bois was right. By discrediting the interpretation advanced by Dunning and his adherents, known as the Dunning School, he changed how the history of Reconstruction is written and understood.

Selective Bibliography Du Bois, W.E.B., Black Reconstruction in America: 1860-1880 (1937, The Free Press, paperback, 1998) Dunning, William Archibald, The Undoing of Reconstruction , The Atlantic, October 1901 _______________________, Reconstruction, Political and Economic, 1865-1877 (1907, Andesite Press, paperback, 2017) Foner, Eric, Black Reconstruction: An Introduction , The South Atlantic Quarterly 112:3, Summer 2013 _________, Reconstruction: America s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (1988, Harper Perennial Modern Classics, updated edition, paperback, 2014) Jones, Martha S., Nine decades later, W.E.B. Du Bois s work faces familiar criticisms , The Washington Post, Jan. 7, 2022 Lewis, David Levering. W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919 1963 (Holt Paperbacks, reprint edition, 2001) Rosen, Hannah, Teaching Race and Reconstruction , Journal of the Civil War Era , Vol. 7, No. 1, The Future of Reconstruction Studies: A Special Issue (March 2017), pp. 67-95 Smith, John David & J. Vincent Lowery, eds., The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction (University of Kentucky Press, 2013) Song, Tommy, William Archibald Dunning: Father of Historiographic Racism Columbia s Legacy of Academic Jim Crow at Columbia University & Slavery (https://columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu/content/william-archibald-dunning-father-historiographic-racism- columbias-legacy-academic-jim-crow) n.d.