Sustainable Tourism Resources and Management

This text delves into the concept of sustainable tourism, emphasizing the importance of maintaining a balance between environmental protection, cultural integrity, and economic benefits. It discusses various tourism resources such as natural and cultural attractions, infrastructure, and support services, highlighting the significance of sustainable management practices. The chapters cover topics like ecotourism, mass tourism, community-based tourism, and pro-poor tourism, offering insights into their potential for sustainable development and benefits for marginalized communities.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

3rd Edition Strategic Management In Tourism Edited by LUIZ MOUTINHO AND ALFONSO VARGAS S NCHEZ

CHAPTER 19 TOURISM RESOURCES AND SUSTAINABILITY DAWN GIBSON

LEARNING OBJECTIVES At the end of this chapter you will be able to: Define sustainable tourism and identify natural and cultural tourism resources; Evaluate mass tourism, ecotourism and community based tourism and their potential for sustainable tourism development; Define pro-poor tourism (PPT) and explain some of the benefits of PPT for poor marginalized communities; Discuss the sustainable management of tourism resources and potential sustainability tools.

1 Sustainable tourism Aims to maintain a balance between protecting the environment; Maintains cultural integrity and establishes social justice; Promotes economic benefits; Meets the needs of the host population in terms of improving living standards both in the short and long term throughout the globe; and Maintains inter and intra-generational equity (Liu., 2003) and viability of the destination for the foreseeable future (Butler, 1993).

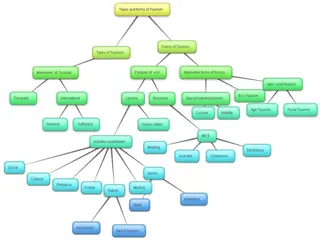

1 Tourism resources Tourism consists of two main types of resources, namely attractions and infrastructure or support services. Attractions vary and can include natural, cultural and built sites as well as special events and festivals, or be associated with recreational activities (Weaver and Lawton, 2014) (see Fig. 19.1). The tourism inventory also includes accommodation, restaurants, transport and other support services.

2 An inventory of tourist attractions Natural Category Site Natural Event Volcanic eruptions TOPOGRAPHY e.g. mountains, canyons, beaches, volcanoes, caves, fossil sites CLIMATE e.g. temperature, sunshine, precipitation HYDROLOGY e.g. lakes, rivers, waterfalls, hot springs WILDLIFE e.g. mammals, birds, insects, fish LOCATION e.g. centrality, extremity Protected areas, hiking trails Scenic highways, scenic lookouts, landmarks, wildlife parks Tides Animal migrations (e.g. caribou, geese) (Source: Weaver and Lawton, 2006, p.130).

2 An inventory of tourist attractions Cultural PREHISTORICAL e.g. Aboriginal sites HISTORICAL e.g. battlefields, old buildings, museums, ancient monuments, graveyards, statues CONTEMPORARY CULTURE e.g. architecture, ethnic neighbourhoods, modern technology ECONOMIC e.g. farms, mines, factories RECREATIONAL e.g. integrated resorts, golf courses, ski hills, theme parks, casinos RETAIL e.g. mega-malls, shopping districts Cultural Battle re-enactments, commemorations, festivals, world fairs Sporting events, Olympics Markets (Source: Weaver and Lawton, 2006, p.130).

2 Sustainable tourism difficult to define To the tourist industry, it means that development is appropriate; to the conservationist, it means that principles articulated a century ago are once again in vogue; to the environmentalist, it provides a justification for the preservation of significant environments from development; and to the politician, it provides an opportunity to use words rather than actions (Butler, 1999, p. 11). The World Tourism Organisation (WTO) defined sustainable tourism development as meeting: ...the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunities for the future. It is envisaged as leading to management of all resources in such a way that economic, social and aesthetic needs can be fulfilled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity and life support in Liu, 2003, p.460). systems (WTO, 2001, cited

3 Sustainable tourism in developing countries Found in the form of ecotourism or community- based tourism. Provides employment, income-generating opportunities, and financing for community projects, which help preserve social ties and prevent out-migration from rural communities. Benefits may accrue to elite factions of the community, with limited benefits to the poor. Where tourism entrepreneurs interested in implementing initiatives that help alleviate poverty, government support and commitment to welfare of citizens essential success (Harrison, 2009).

3 Ecotourism and Community based tourism (CBT) In developing countries, e.g. Fiji, ecotourism and community-based tourism developed as complementary to more conventional mass tourism products, Found in the form of activities, e.g. village visits, cultural performances, and nature treks. Recently indigenous entrepreneurs and communities have developed budget resorts and village stays, catering for backpackers and independent travellers (see case study).

3 Tools of sustainability (See Table 19.1) Consultation/ participation techniques Codes of conduct (tourist, industry and hosts) Sustainability indicators Footprinting Certification Sustainable livelihoods framework 1. Area protection 2. Industry regulation 3. Visitor management techniques 4. Environmental impact assessment (EIA) 5. Carrying capacity calculations (Source: Mowforth and Munt, 2016, pp. 114 115).

3 Ecotourism defined Ecotourism is a form of tourism that fosters learning experiences and appreciation of the natural environment, or some component thereof, within its associated cultural context. It has the appearance (in conjunction with best practice) of being environmentally and socio-culturally sustainable, preferably in a way that enhances the natural and cultural resource base of the destination and promotes the viability of the operation (Weaver, 2004, p. 15).

3 Ecotourism has critics but Has the potential to aid in protecting endemic species, and to provide alternative or supplementary livelihoods and potentially alleviate poverty (Farrelly, 2009, p.2); Can empower local communities (Scheyvens, 2000; Sofield, 2003). Can contribute to conservation and revival of endangered cultures, but can also damage local cultures, economies, and environments (de Kadt, 1979; Weaver, 1998); and With suitable planning and management, ecotourism can be used as a tool to promote conservation and sustainable development in poor, remote rural areas.

3 Community based tourism (CBT) CBT aims to improve the quality of life of the community residents by: maximizing local economic benefits; conserving the national and built environment; and providing visitors a high quality, value for money experience (Park and Yoon, 2009; Park et al., 2008). More sustainable forms of tourism have concentrated on a community development approach (Goodwin and Santilli, 2009). Community refers to people who share a sense of purpose and common goals (Joppe, 1996). These may be geographical, or based on heritage and cultural values.

3 CBT defined Tourism development, which considers the needs and interests of the popular majority, alongside the benefit of economic growth. Community-based tourism development would seek to promote the economic, social, and cultural well-being of the popular majority. It would also seek to strike a balanced and harmonious approach to development that would stress considerations such as the compatibility of various forms of tourism with other components of the local economy: the quality of development, both culturally and environmentally; and the divergent needs, interests, and potentials of the community and its inhabitants (Brohman, 1996, p.60).

3 Pro-poor tourism (PPT) PPT is an approach to tourism development, which asserts: that greater benefits from tourism can be spread to the poor by encouraging a wide range of players (community, private sector, civil society, government) working at a range of scales (local, national, regional) to spread the benefits of tourism more widely and unlock livelihood opportunities for the poor within tourism and connected sectors. This can lead to improvements, for example, in policy, in labour practices of hotels and resorts, and better linkages between related sectors such as agriculture and fisheries (Scheyvens and Russell, 2010, p.1).

3 Pro-poor tourism benefits (see Table 19.2) Increase economic benefits Increased local employment, wages, commitments to local jobs, training of local people. Expand local enterprise opportunities including those that provide services to tourism operations, e.g. food suppliers, and those that sell to tourists, e.g. handicraft makers, guides, cultural performers. Enhance non-financial livelihood impacts Capacity building training Minimize environmental impacts Monitor use of natural resources Improve social and cultural impacts Increase local access to infrastructure and services provided for tourists, e.g. roads, communications, healthcare and transport Enhance participation and partnerships Create more supportive policies and planning framework that enables participation by the poor Increase participation of the poor in government and private sector decision making Build pro-poor partnerships with the private sector Increase flow of information and communication between stakeholders (Source: Pro-poor Tourism Partnership, 2004, p.1).

3 PPT benefits in Fiji Different scales of tourism development in Fiji can greatly contribute to three determinants of poverty alleviation as identified by Zhao and Ritchie (2007) opportunity, empowerment and security. Opportunities can provide direct and indirect benefits to the poor. Examples include: lease money; employment; contributions to community development, e.g. housing, power, water; payment of church tithes; traditional obligations and education. Untapped opportunities can increase tourism benefits and expand backward linkages between tourism and local economy and reduce heavy reliance on imported goods, especially amongst large-scale properties, e.g. increase linkages to local agriculture, farmers and fishermen (Scheyvens and Russell, 2012).

3 Tourism and the environment The environment (includes socioeconomic, cultural and biophysical elements) is both a resource and a constraint to tourism development (Pigram, 1992) Tourism development has brought about both positive and negative impacts Relationship between tourism and the environment can be better examined in terms of nature, scale and pace of environmental manipulation

3 Alternative tourism Are some forms of tourism more suitable in certain settings? Realization led to review of alternative tourism and tourism typologies considered preferable to mass tourism (Pearce, 1992) Alternative tourism involves approaches such as ecotourism, community based tourism, agrotourism, responsible tourism etc. considered more sustainable and ethical (Mowforth and Munt, 2016).

3 Alternative tourism approaches to mass tourism Economic issues Socio-cultural factors Relationship to the environment Host community participation Development of ST strategies that provide more equitable economic benefits to host destinations Ecotourism can be an approach that enables economic development and environmental protection whilst protecting wellbeing of local communities.

3 Policy and implementation Tendency to view tourism as a private sector industry which is determined by market forces Recent attention paid to role of government and public sector if tourism development is be sustainable and contribute to poverty alleviation (Harrison, 2008; Scheyvens and Russell, 2012). Harrison (2008) argues: for poverty alleviation to be of any significance it must be supported by state or governments. the impacts of any pro-poor tourism project, even if on a large scale, are likely to be limited unless a state s entire tourism strategy is constructed around poverty alleviation (2008, p.71). Sustainable pro-poor policies need strong institutions capable of proactively intervening in market forces and redistributing financial resources (Schilcher, 2007, p.71).

3 Summary Tourism destinations require sustainable management of limited resources. Chapter discussed tourism resources and sustainability, approaches to tourism and a number of specific examples from the Fiji Islands. Chapter also examined concepts of sustainable tourism, pro-poor tourism, and interdependency of tourism and environment. There is a need to maintain a balance between environmental protection, cultural integrity, social justice and promotion of economic benefits that meet needs of host populations. Different types of tourism can offer more potential sustainable solutions using tools for sustainability that can provide more sustainable resource management.

3 Review questions 1. Conduct an inventory of tourism attractions and resources in your state or country (see Fig. 19.1). Explain the difference between sustainable tourism and pro-poor tourism. Outline, with examples, how different types of tourism might be more sustainable than others. Discuss the initiatives that could be implemented to make mass tourism more sustainable. Identify the different types of resource management initiatives that can be used in the following: a National park, the development of a new resort; a wildlife sanctuary and a heritage town. Having read the case study on Wayalailai, locate two or three tourism operators in your area. With regards to the management or use of local resources, identify the extent to which they use/purchase local resources, what benefits they offer the local community, and whether they practise pro-poor initiatives (see Table 19.2). Finally, suggest how you think they could better manage their resources. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6.

References Butler, R.W. (1993) Tourism an evolutionary perspective. In: Nelson, J.G., Butler, R.W. and Wall, G. (eds) Tourism and Sustainable Development: Monitoring, Planning, Managing. Department of Geography Publication Series 37, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Canada, pp. 29 43. Butler, R.W. (1999) Sustainable tourism: a state-of-the-art review. Tourism Geographies 1(1), 7 25. De Kadt., E. (ed) (1979) Tourism: Passport to Development? University Press, for the World Bank and UNESCO, Oxford. Farrelly, T.A. (2009) Business va avanua: cultural hybridisation and indigenous entrepreneurship in The Bouma National Heritage Park, Fiji. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. http://mro.massey.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10179/1166/02_whole.pdf?sequence=4 (accessed 10 May 2016) Harrison, D. (2008) Pro-poor Tourism: a critique, Third World Quarterly 29(5), 851 868. Harrison, D. (2009) Pro-poor tourism: is there value beyond whose rhetoric? Tourism Recreation Research 34(2), 200-202. Kerstetter, D. and Bricker, K. (2009) Exploring Fijian s sense of place after exposure to tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 17(6), 691 708. Liu, Z. (2003) Sustainable tourism development: a critique. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 11(6), 459 475. Mowforth, M. and Munt, I. (2016) Tourism and sustainability. Development, Globalisation and New tourism in the Third World, (4th edn.). Routledge, London. Park, D. and Yoon, Y. (2009) Segmentation by motivation in rural tourism: A Korean case study. Tourism Management 30, 99 108. Park, D., Yoon, Y., and Lee, M. (2008) Rural community development and policy challenges in South Korea. Journal of the Economic Geographical Society of Korea 11, 600 617. Pearce, D.G. (1992) Alternative tourism: Concepts, classifications and questions. In: Smith, V.L. and Eadington, W.R. (eds) Tourism Alternatives: Potentials and Problems in the Development of Tourism, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, pp. 15-30. Pigram, J.J. (1992) Alternative tourism: Tourism and sustainable resource management . In: Smith, V.L. and Eadington, W.R. (eds) Tourism Alternatives: Potentials and Problems in the Development of Tourism, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, pp. 76 87. Scheyvens, R. and Russell, M. (2010) Sharing the Riches of Tourism. School of People, Environment and Planning, Massey University, Palmerston North. Scheyvens, R. and Russell, M. (2012) Tourism and poverty alleviation in Fiji: comparing the impacts of small- and large-scale tourism enterprises. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 20(3), 417 436. Schilcher, D. (2007) Growth versus equity: The continuum of pro-poor tourism and neoliberal governance. In: Michael Hall, C (ed.) Pro-poor Tourism: Who Benefits? Channel View Publications, Clevedon, pp. 56 83. Weaver, D.B. (1998) Ecotourism in the Less Developed World. CAB International, Wallingford. Weaver, D. (2004) Mass tourism and alternative tourism in the Caribbean, In: Harrison, D. (ed.) Tourism and the Less Developed World: Issues and Case Studies.CAB International, Wallingford, pp. 161 174. Weaver, D.B. and Lawton, L.J. (2006) Tourism Management (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd., Milton. Weaver, D.B. and Lawton, L.J. (2014) Tourism Management (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd., Milton. Zhao, W. and Brent-Ritchie, J.R. (2007) Tourism and poverty alleviation: An integrative research framework. Current Issues in Tourism 10(2&3), 119 143.