Crafting Your Research Argument

Learn how to effectively craft your research argument by developing a strong claim, supporting it with logical reasons, and presenting credible evidence. Discover the importance of outlining, organizing, and creating a bibliography for your research paper.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Who Says? Holdstein & Aquiline, Chapter 8 Writing, and crafting your research 1

Crafting your argument Note that "argument" here is a term for a position or claim, not a dispute. Main parts: 1. Claim = answer to your RQ; often answers the "So what?" question; avoid bias; make it debatable 2. Reasons = claim is supported because this shows your line of thought; is it logical? 3. Evidence = your research; data is important; credible; relevant This paper argues that (claim) because of (reasons) based on (evidence). Stop and Consider: Have a friend play devil s advocate and try to counter-argue or find holes in your argument 2

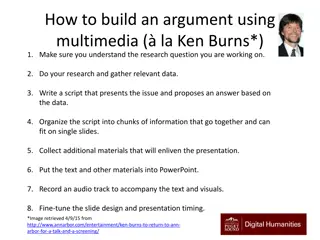

Organizing Consider making an outline Collect all your notes, printouts. Look for gaps in the materials Distinguish between specific passage you ill cite/paraphrase and general statements you can make based on your knowledge 3

Outlining This is usually a form of pre-writing for your draft, although some start the draft before the outline. The outline should include: Why you chose this topic Your research questions and thesis statement [ the answer to the main question] The evidence that will help make your argument (support your thesis) Brief summary of ideas that come from each source with short citations (e.g. discuss Smith results ); this leads to annotated bibliography What have you learned, concluded [and what would you need to know next?] Format is up to you [see handout, assignment]; formal (I then A, B etc.) or informal often a list of questions: How serious is X? 4

Bibliography [Technically, a bibliography is an exhaustive list on your topic; you are collecting a list of References or Works Cited] Annotations that you have been doing will help you organize your outline. Usually include summary, relevance [and author/source ethos] No need to include the annotations with your final paper, just the Works Cited list in alphabetical order. 5

Title This matters. [Academic papers often have two parts with a colon, as in our Snapchat paper. Don t just a label title (e.g. Internet Addiction)] Even a working title can help you focus your paper 6

Planning and drafting You might both do an outline and write some of the paper [that s why you were asked for the intro and conclusion with the optional outline] There s a good list of what you need to begin a full draft on p. 120. It reflects the process approach we have used during the semester. Note that they suggest Thesis is focused You have supporting arguments backed by evidence You might not have a clear introduction yet You have to start at some point Don t worry about spelling etc. on the first draft 7

The written structure Intro/body (several pages)/conclusion Consider subheadings for these, and within the body Intro might be last thing you write Structures can be: Chronological Narrative Familiar to less-familiar Inductive from specifics to general conclusion [Deductive] General statement, then evidence [most research papers are like this] Compare and contrast Cause and effect Definition [note these last two are not argument papers] Be sure to make good use of transitions 8