Mastering the Art of Argument in Essay Writing

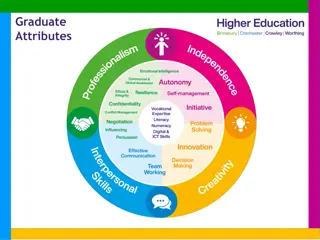

Embrace the challenges of essay writing by understanding the essence of crafting a strong argument. Learn how to structure your thoughts logically, present evidence convincingly, and engage your readers effectively. Discover the importance of argument in various fields of life and the vital role it plays in English studies.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Long Essays/ Dissertations. Argument

Basics 1. Do not be frightened. People have done it before. It s just a kind of work. 2. OK, writing can be hard work, but it is creative: you order your thoughts, you turn a muddle into a thing, you express something, make something. Relish this. Enjoy it! 3. You are communicating, so write with a reader in mind! Tell them about something you ve found; they didn t know.

Argument is one of the 5 Criteria Needs to be: 1. Clear, lucid. 2. Cogent. 3. Well evidenced. It s important because it affects all the other criteria. The brain, the skeleton, the heart, the lungs of the essay. But what is an argument? Definition (one of the techniques). Monty Python: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lvcnx6-0GhA

Collected series of statements intended to establish a proposition Three things 1. There s a proposition. 2. There are some statements which are supposed to establish the proposition. 3. They ve been collected . (But, be critical) what does this miss out? That the statements have been arranged, not just collected . And the arrangement needs to follow a logical sequence.

Arguments can be simple Syllogism: All humans are mortal. I am a human. Therefore I am mortal. Example in English Lit: According to The Revengers Tragedy , when the bad bleeds then is the tragedy good. In this tragedy the bad bleed, but so do the good so the tragedy is both good and bad. And so? Simple. Build up - how to flesh out for longer essays?

Arguments exist In many areas of life: law medicine policy documents management editing texts journalism research at University or elsewhere. Argument is vital. We should think about it.

But argument in English Is always expected in an essay. But is rarely taught. Why? heart of studying English. Not one approach, not one essay structure . Explore, learn to explore different techniques, be adaptable to different material, diverse advice. Relation to facts , evidence ? It is not systematic, not programmed. Be prepared to lose your bearings: an education in scepticism. And yet you need one. There are tricks to get you through.

Diverse advice: the strict Eric Langley: My thesis supervisor, would make me write alongside each paragraph a very short, very simple, single-claused sentence saying exactly the thesis-function of that paragraph. So I would have a list of say 20 of these statements, and in my supervisions he would read them out in order, one by one, and lay them on the desk, asking me do these follow on from each other? Are they in the right order? Why is this statement coming before this one? etc, and then what links these two statements? Is it a but , an and ?, a therefore ? etc. It was arse-achingly irritating, but it did make me super self-conscious about the drive of my thesis. Doug Cowie: 1) A simple, yet specific and detailed thesis statement is vital. 2) Make sure that each paragraph you write relates DIRECTLY to the thesis statement. 3) Introduce an idea, quote the author to support, explain the quotation, analyze the quotation in context of your argument, ie, WHAT does it mean and WHY does that matter? 4) Write the introduction last; you cannot introduce an essay you haven't written any more than you can introduce a person you haven't met.

Diverse advice: lenient. Betty Jay: some essays are discursive rather than argumentative. Sometimes, the argument and conclusion relates to the exploration of a specific problem that the text poses and for which there is no resolution. For example, one hundred and fifty years of arguing about Bertha in Jane Eyre takes us from the question of conventional endings to a text, through to feminist disquiet and on to post-colonial readings: but the verdict depends on the jury. They should not be afraid to say that there is no resolution but we are certainly interested in what happens when they approach the issue, how they read those other critical interventions and so on. In other words, they should remember that uncertainty is a literary value, as is ambiguity and irresolution. Ben Markovits: University students should, at least by the third year, have gotten out of the idea that an essay has a set formal structure which they have to follow. I don't want them to think that writing means jumping through hoops. They should support what they say, they should show an awareness of the counterarguments, they should tell a story, they should make one part of the essay lead into another, and they should realize that half the battle of persuasion is achieved by elegance, etc. What makes an argument in the context of an English class? The space between the obvious and untrue is very narrow, and that they have to find a way of occupying it. One test of an argument is whether or not its opposite can plausibly be argued -- if it can, I tell them, and they can make their own point of view stick, then they've probably done something interesting

Problems/ opportunities 1. The proposition. (Finding your thesis. Thinking) 2. Gathering the statements. (Research the literature review.) 3. Arranging them in a sequence. Using logic. Structuring the whole. Flesh out the basic structure of the argument.

1a. Finding the proposition Your thesis, the thing you show, argue, prove. Could be as short as a sentence. Can be longer. How to find it? First: you like something and want to write about it. I like so and so why? What does it remind me of? Don t find the evidence to fit claim. Go the other way round remain open to change. That s the exploration. Develop a hunch, identify an issue, and ask questions about it. Try out some hypotheses. Develop a question. Step around the issue. Build up a string of questions Move them around. Check what people say about the question. Develop a claim. Set up the possible proposition. Eventually you ll find one: it should not be obvious, but plausible. Keep the option that your final proposition is: we cannot know . Allows you to be discursive not necessarily argumentative (Betty Jay).

1b. Examples of kinds of proposition/ argument James Smith: 1. You d think this would be the case, but it turns out this is 2. These two texts seem to be different, but in one crucial way they are surprisingly similar 3. These two texts seem similar, but in one crucial way they are utterly different Also: 4. People have said this, but they ve ignored this. Check: can its opposite be plausibly argued, but your argument still sticks? OK go!

2. Gathering evidence, generating material You ve got a topic, an issue, a series of questions, some primary texts. Now find the evidence. Read the primary texts carefully. Survey the critical field. Take notes, ask questions, check definitions. Always define and redefine - your terms. Hunch claim and then a draft proposition. Literature Review: Organize views and counter-views. Exposition (fleshes out). Describe a position; criticise it. Support/dismantle. Describe an alternative position; criticise it also. Compare them both. Find a third position your own.

3. Arranging in a sequence with a view to fleshing out The plan. Keep the proposition in view. Start simple: A,B,C . Beginning, middle, end. The middle is the battle ground! Group your materials around issues. Get off the screen! Begin to layer: this will be the body of your essay. Arrange the issues in a logical connected way. Try spider-grams, flow charts, lists of stations. A3 paper. Arrows. Think of connections, and transitions: And , Moreover, , Furthermore , Also : By contrast , However, Whereas , And yet , Nevertheless , Even so , Because , Thus, therefore , consequently. Things can be in series and in parallel. Sections and sub-sections. Look for thesis/antithesis/synthesis. Do another plan (because you ll have tried to cram stuff in). Think of kinds of connections:

3a Fleshing out listicles, expositions, surveys, literature reviews. Use light signposting. Don t be an accountant. An exploration of X will make up the majority of this dissertation. As we have seen . Consider other stylish connectives (quotations, short punchy sentences after longish ones). Write the intro and the conclusion last. Be stylish, elegant, persuasive. Evaluate: both the primary and the secondary texts. Call on the power of literature, honour it, draw on it to help it is your companion, not your adversary. And Remember the basics

Return to basics 1. Do not be frightened. People have done it before. It s just a kind of work. 2. OK, writing can be hard work, but it is creative: you order your thoughts, you turn a muddle into a thing, you express something, make something. Relish this. Enjoy it! 3. You are communicating, so write with a reader in mind! Tell them about something you ve found; they didn t know.

Essay planning Some things Introductions can do: Lay out key issues without giving answer Explain your approach An unexpected quotation from the text that opens up the essay topic Important contexts for your argument

Essay planning Some things Conclusions can do: Highlight key arguments Revisit the essay title Revisit the introduction Provide a powerful final quotation

Time Management (draft) First draft (aim under the word count) (3 days) Second draft (hit the word count) (2 days) The final version will give yourself half a day to proof read 6000 words. (1 day) 2000 words in a day is good going. Always easier if you ve got lots of material. Plan: half a day. Research: 1 week. But they won t be very good words. 2 weeks per 6-8000 word essay. (You ll need to do 3.5 of these. 7 weeks total. Your last essay deadline is in May.