Eugene A. Nida - Pioneer of Dynamic Equivalence Bible Translation Theory

Eugene A. Nida (1914-2011) was a linguist who revolutionized Bible translation theory with his concept of dynamic equivalence. Through works like "Toward a Science of Translating," he shaped modern translation studies. Nida's theory distinguishes between formal and dynamic equivalence, favoring the latter for its natural closeness. This dynamic approach aims for effective communication in both source and target languages.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Who is Eugen A. Nida? Eugene A. Nida (November 11, 1914 August 25, 2011) was a linguist who developed the dynamic-equivalence Bible-translation theory and with his book of 1964 (Toward a Science of Translating) he is considered as one of the founders of the modern discipline of translation studies. His attempt with the above book and another appeared in 1969, the co-authored (Nida and Taber) The Theory and Practice of Translation , was to make the process and the analysis of translation more systematic.

Nida s theory Eugene Nida s theory of translation developed from his own practical work from the 1940s onwards when he was translating and organizing the translation of the Bible Nida s theory took concrete form in two major works in the 1960s: Toward a Science of Translating (Nida 1964a) and the co-authored The Theory and Practice of Translation (Nida and Taber 1969). The title of the first book is significant; Nida attempts to move Bible translation and translation in general into a more scientific era by incorporating recent work in linguistics. His more systematic approach borrows theoretical concepts and terminology both from semantics and pragmatics and from Noam Chomsky s work on syntactic structure which formed the theory of a universal generative transformational grammar (Chomsky 1957, 1965). Nida's theory of translation is characterized by the distinction between two types of equivalence: formal equivalence and dynamic equivalence, but he was in favor of dynamic equivalent, arguing that it is the closest natural one.

Nida s Formal Equivalence Formal equivalence or correspondence pays special attention to the message itself, in both form and content , (Nida, 1964:159). To put this differently, formal equivalence is text/author-oriented, representing the closest form-based equivalent of SL elements. Examples of this type are as follow: . translated into English as: The eye can see but the hand cannot reach . . translated into English as: A journey of a thousand miles starts with a step. Formal equivalence approach tends to emphasize fidelity to the lexical details and grammatical structure of the original language rather than to the content of the message. Similar to the aforementioned argument, Hatim and Munday (2004) hold that this type of equivalence does not always serve the message of the source text when translating it into the target language, i.e., translating the original linguistic unit, the grammatical structure, and punctuation and neglecting the meaning and the extra linguistic factors of the original text may lead to violation of some aspects while translating. In order to mark the difference between the formal translation and the dynamic one, look at the same aforementioned examples being translated dynamically: A moneyless man goes fast through the market. From small beginnings comes great things.

Nida s Dynamic Equivalence Nida s theory was named after the name of this type of equivalence. According to Nida, dynamic equivalence, the term as he originally coined, is the "quality of a translation in which the message of the original text has been so transported into the receptor language that the response of the receptor is essentially like that of the original receptors. Examples of Dynamic equivalence are as follow: Like will to like. Will be: . . Familiarity breeds contempt. Will be: . . Nida s desire out of this type of translation is to make the reader of both languages (source and target) understand the meanings of the text in a similar way. For Nida, dynamic equivalence represents the faithful translation of the ST in so far as it generates a response similar to the one first exercised on the original readers or hearers. In later years, Nida distanced himself from the term "dynamic equivalence" and preferred the term "functional equivalence". What the term "functional equivalence" suggests is not just that the equivalence is between the function of the source text in the source culture and the function of the target text (translation) in the target culture, but that "function" can be thought of as a property of the text. It is possible to associate functional equivalence with how people interact in cultures. Functional in this sense is similar either to closest natural equivalence or the cultural equivalence. Because functional equivalence approach avoids strict adherence to the grammatical structure of the ST in favor of a more natural rendering of TT, it is sometimes used when the readability of the translation is more important than the preservation of the original grammatical structure. In order to mark the difference between the dynamic translation and the formal one, look at the same aforementioned examples being translated formally: . . . .

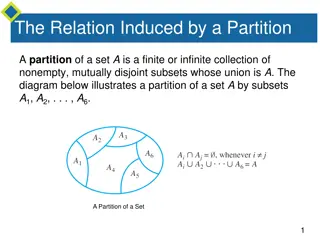

Nida s three stage approach SL= Source Language TL= Target Language Stage 2 Stage 1 Stage 3 Restructuring X Y (B) The TLT (A) The SLT Analysis Transfer

Chomskys generativetransformational model analyses sentences into a series of related levels governed by rules. In very simplified form, the key features of this model can be summarized as follows: Nida Nida s three s three stage approach stage approach (1) Phrase-structure rules generate an underlying or deep structure which is SLT SLT= Source Language Text TLT TLT= Target Language Text (2) transformed by transformational rules relating one underlying structure to another (e.g. active to passive), to produce (3) a final surface structure, which itself is subject to phonological and morphemic rules. The most basic structures in Chomsky s TGG are kernel sentences, which are simple, active, declarative sentences that require the minimum of transformation (e.g. the wolf attacked the deer). This sentence does not require transformation to kernels; but the following The power of his will can end the game. , if analyzed into the kernels will be: (1) The will has power. (2) He has a will. (3) He wills to do something (4) H e has a will which has power. (4) He can end the game with the power of the will he has/uses quickly. Nida incorporates key features of Chomsky s model into his science of translation. In particular, Nida sees that it provides the translator with a technique for decoding the SLT and a procedure for encoding the TLT (Nida 1964a: 60). Thus, the surface structure of the ST is analyzed into the basic elements of the deep structure; these are transferred in the translation process and then restructured semantically and stylistically into the surface structure of the TT. This three-stage system of translation (analysis, transfer and restructuring) is meant to obtain the dynamic equivalence devised by Nida (see the figure on the side of this page).

kernels are the basic structural elements out of which language builds its elaborate surface structures. Nida Nida s three ( (Application Application) ) s three stage approach stage approach In Nida s model, Kernels are to be obtained from the ST surface structure by a reductive process of back transformation. By using Chomsky s generative transformational grammar s four types of functional class, the SLT could be analyzed in terms of: SLT SLT= Source Language Text TLT TLT= Target Language Text (1) events: often but not always performed by verbs (e.g. run, fall, grow, think); (2) objects: often but not always performed by nouns (e.g. man, horse, mountain, table); (3) abstracts: quantities and qualities, including adjectives and adverbs (e.g. red, length, slowly); (4) relationals: including affixes, prepositions, conjunctions and copulas (e.g. pre-, into, of, and, because, be). Let s take an example to initiate the first stage of Nida s model, namely, ANALYSIS Stage 1 : (SLT Analysis) The power of his will could end the game quickly. This will be back-transformed into the kernels and the four functional classes: 1. The ( will = object/event) (has= event) (power=object/event). 2. (He (a person) = object) (has/uses)= event) a (will= object/event). 3. (He= object) (wills = event) (to= relational) (do=event) (something= object/event (ending the game). 4. (He= object) (has= event) a ( will = object/event) (which= relational) (has= event) (power =object/event). 5. (He= object) (can /has the ability= event) (end=event) the (game= object/event) (with= relational) the (power =object/event) (of=relational) the (will= object/event) (He= object) (has/uses)= event) (quickly=abstract/eventl)

Nida Nida s three s three stage approach stage approach ( (Application Application) ) Stage 2 : (SLT Transfer) The power of his will could end the game. Nida and Taber (ibid.: 39) claim that all languages have between six and a dozen basic kernel structures and agree far more on the level of kernels than on the level of more elaborate structures such as word order. SLT SLT= Source Language Text TLT TLT= Target Language Text Kernels are the level at which the message is transferred into the receptor language before being transformed into the surface structure in a process of: (1) literal transfer ; (2) minimal transfer ; and (3) literary transfer . Literal transfer of SLT into the TLT: The power of his will could end the game quickly. The SLT is transferred literally; here the translator has to translate the text word for word, keeping the line of the SLT word order. Minimal transfer of SLT into the TLT: The power of his will could end the game quickly. The SLT is transferred minimally; here the translator has to rearrange the linguistic elements in a way that will match the TL rules in terms of word order and structures, including the syntactic and morphological ones Literary transfer of SLT into the TLT: The power of his will could end the game quickly. . . . The SLT is transferred literarily into the potential of the above options; here the translator could have, stylistically speaking, more than one option in translating the SLT , depending on the contextual and co-textual variables.

Nida Nida s three ( (Application Application) ) s three stage approach stage approach Stage 3 : (TLT Restructuring) The power of his will could end the game. Nida (1964) & Nida & Taber (1969) emphasize the importance of pragmatic knowledge in translation. This aspect of linguistics is translated in his theory as part of rules contextual rules, where the translator must adjust his translation in accordance with the TL context and the audience s expectations consistently. SLT SLT= Source Language Text TLT TLT= Target Language Text Stage 3 : (TLT Restructuring ) The power of his will could end the game. The translator has to read well the context of the TLT and cast it in a way that would appropriately sound natural for the target readers, pragmatically and stylistically; he/she must come out with just one option from the potential of the options resulting from the final stage of the transfer process (the literary one), for example, for the above sentence, one may choose the following TLT to viably meet the TLT readers expectations: . Here , you may see that options such as are decided on as to rule out what is inappropriate for TT context.

Criticisms to Nida Criticisms to Nida s theory s theory Formal equivalence is sometimes seen as mechanical, distorting the message of the ST, and requiring the reader to work unduly hard to understand the TT. Lefevere (1993: 7) felt that equivalence was still overly concerned with the word level, rather the text level. Van den Broeck (1978: 40) and Larose (1989: 78) considered equivalent effect or response to be impossible (& difficult to measure in the target audience/readers. The dynamic equivalence he suggested could be seen as subjective in nature; all things are conditioned by the translator s perspective. The questions that remain unanswered, given the subjectivity inherent in both the principle of equivalent effect and the translator s options, are: Is Nida s theory really scientific ? & is it applicable in real life practice of translators?