Unveiling Hidden Themes in Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Analysis of "My Mistress' Eyes Are Nothing Like the Sun

Delve into the concealed themes of pagan religion, solar energy, and fossil fuels in Shakespeare's Sonnets through an intricate analysis of selected poems. Explore the allegorical use of sun worship and the underlying message of procreation intertwined with religious motifs in Sonnet 7.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

PRESENTATION ON MY MISTRESS EYES ARE NOTHING LIKE THE SUN : HIDDEN LOVERS IN SHAKESPEARE S SONNETS Presented by Prof. Madhvi Kotwal Department of English Govt P.G College Rajouri.

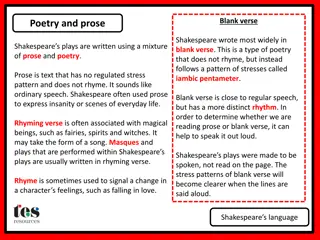

MY MISTRESS EYES ARE NOTHING LIKE THE SUN : HIDDEN LOVERS IN SHAKESPEARE S SONNETS Is it possible to look for the themes that Shakespeare hid in Hamlet and other plays---themes such as pagan religion, solar energy and the harmful aspects of fossil fuels---in his Sonnets as well? The answer is definitely yes. In this paper, I ll analyze a few of Shakespeare s Sonnets for these themes. Thirteen of the Sonnets use the word sun directly. Many others do not use the word sun but refer to the sun in another way. In Sonnet 7, we see pagan sun worship concretely appear in the orient (that is, Asia) and it s shown in a positive light.

TEXT Lo! in the orient when the gracious light Lifts up his burning head, each under eye Doth homage to his new-appearing sight, Serving with looks his sacred majesty; And having climb'd the steep-up heavenly hill, Resembling strong youth in his middle age, yet mortal looks adore his beauty still, Attending on his golden pilgrimage; But when from highmost pitch, with weary car, Like feeble age, he reeleth from the day, The eyes, 'fore duteous, now converted are From his low tract and look another way: So thou, thyself out-going in thy noon, Unlook'd on diest, unless thou get a son.

EXPLANATION Religious words like gracious , homage , sacred , heavenly and pilgrimage surround the sun as it climbs up and makes its journey across the sky. When the sun gets to the top of the meridian ( highmost pitch ), it starts to sink down into the horizon, the people ( mortals ) who were looking at it look another way . Regarding this change in what people are looking at, Shakespeare uses the word converted , used to mean simply changed (the eyes of people are converted to look another way) but converted could also be signaling a secret change in Shakespeare s own religious inclinations. He has until now used the heavily religious words like gracious , homage , sacred , heavenly and so forth about the sun, so if we then take converted as a religious word too, it may be a subtle message about his own religious views. That is to say, he wasn t too shy to use religious words playfully in the context of sun worship in this poem, so why not include converted too, and who else is in the poem to be converted except for the narrator/poet himself? It s a clever rhetorical method to send a signal. Technically, the first 12 lines of the poem, about the sun in the orient and its worshipers, are the conceit or the device to make an elaborate allegory or comparison to use to promote the so-called real message of last two lines of the poem ( So thou, thyself outgoing in thy noon,/ Unlook'd on diest, unless thou get a son ). Here we see the poet/narrator exhorting what critics call the fair young man (an unknown or perhaps fictive person or persona who is often used in Shakespeare s Sonnets as the receiver of a message ) to procreate. But this image of procreation is probably just another conceit, just as the fair young man himself is not a real person, but an image of mankind. According to my research, Shakespeare s plays are concerned with human interaction with fossil fuels, the Christian religious background preceding and enabling this interaction, and the eventual outcome of this interaction1 , so it would be strange if Shakespeare s Sonnets were not also concerned with this same central issue. The idea of procreation ( get a son ) is a conceit expressing the continuity of humans after fossil fuels are gone. Shakespeare seems to have been concerned about environmental issues. Moving on to what is perhaps Shakespeare s most famous sonnet of all, Sonnet 130, ( My Mistress Eyes Are Nothing Like the Sun ), this theme of sun worship is also provided covertly and playfully:

TEXT My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damask'd, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground: And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare.

EXPLANATION The words I have put in a sunny yellow color subtly and subconsciously direct the reader to the message that Shakespeare s (or the narrator, but in this case I think they are the same) goddess (or his mistress) is the sun and other beautiful ( delight ful) natural things that arrive on our planet thanks to the sun s energy: snow, roses, coral, even music is included. (Apollo was the god of music and the sun; actually music and the sun are connected in a basic way for some reason and in Japanese, the word music includes the kanji sun twice.) The sun s rays are bright white sometimes and also red (in the evening and morning), so those colors in particular are included. (In Japanese the color white is written and it has the kanji for sun also in it, for the same reason that the sun s rays are mostly seen as white.) The words heaven and my love at the end complete this rapturous expression of devotion to the natural sun goddess. No wonder it is his most famous Sonnet; the simplicity of the message and its clarity are absolutely stunning and piercing. Readers have been able to sense his fervor and his passion. (The same technique is used in Romeo and Juliet, where Juliet s identity as the sun is hinted at in these lines:

TEXT Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven, Having some business, do entreat her eyes To twinkle in their spheres till they return. What if her eyes were there, they in her head? The brightness of her cheek would shame those stars, As daylight doth a lamp; her eyes in heaven Would through the airy region stream so bright That birds would sing and think it were not night

EXPLANATION (In these lines from Romeo and Juliet, the yellow words also transmit Juliet s identity as the sun). This sort of technique---a rhetorical surface message makes use of words with linked meanings that express something else under the surface---- seems to have been one of Shakespeare s favorite ones. Next, in Sonnet 10, the line seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate echoes Hamlet s sad and famous description of the sky as the air, look you, this brave o erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire, why, it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors (II.ii.302-306). Both are cloaked allusions to coal smoke.2 Once again, Sonnet 7 is technically addressed to the so-called fair young man and exhorts him to procreate ( make thee another self ). Again, this fair young man is mankind. Now he is unprovident and seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate , which is a signal, as in Hamlet for producing coal smoke (which blackens the sky):

TEXT For shame! deny that thou bear'st love to any, Who for thyself art so unprovident. Grant, if thou wilt, thou art beloved of many, But that thou none lovest is most evident; For thou art so possess'd with murderous hate That 'gainst thyself thou stick'st not to conspire. Seeking that beauteous roof to ruinate Which to repair should be thy chief desire. O, change thy thought, that I may change my mind! Shall hate be fairer lodged than gentle love? Be, as thy presence is, gracious and kind, Or to thyself at least kind- hearted prove: Make thee another self, for love of me, That beauty still may live in thine or thee.

EXPLANATION Polluting and defiling the earth is a horrible thing in Shakespeare s eyes, which he likes to being possess d with murderous hate and also an act against humanity in general ( That 'gainst thyself thou stick'st not to conspire ). The narrator reminds the fair young man thatliving an environmentally-friendly life (that is seeking to repair the beauteous roof that is the sky) should be thy chief desire . And the poet wants to see mankind reformed: O, change thy thought, that I may change my mind! so that in this case the make thee another self (technically a rhetorical procreation message in the conceit) actually signals more the idea of changing humanity s environmentally conscious. In Sonnet 15, the fair young man faces aging and death, for natural things in general are at their peak only a little while because everything that grows Holds in perfection but a little moment . Shakespeare openly characterizes the situation of mankind in this Sonnet When I perceive that men as plants increase, Cheered and cheque'd even by the self-same sky, Vaunt in their youthful sap, at height decrease.. but, even knowing what is natural, of course, he has hopes to be a helpful influence on the fair young man : thinking and becoming more