The Separation of National Security Powers

The separation of national security powers involves the formalist view where Congress makes laws, the Executive executes them, and the courts interpret them. The branches' powers are often blurred, with Congress able to delegate lawmaking power to the Executive. The Executive can also acquire customary authority, while the President, as Commander in Chief, may act without express statutory authority under certain circumstances. Our constitution does not grant the head of state general emergency powers, but emergency powers can be delegated by Congress.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

THE SEPARATION OF NATIONAL SECURITY POWERS: SUMMARY OF BASIC PRINCIPLES

Under the formalist view of the separation of powers, Congress makes the laws, the Executive executes the laws, and the courts interpret the laws. Taking this view, the opinion for the Court in The Steel Seizure Case held that, because President Truman s order both made and executed policy, he had usurped the lawmaking power of Congress.

In fact, the respective powers of the branches are more blurred. First, Congress can by statute delegate lawmaking power to the Executive, provided that it makes policy by establishing statutory standards for the exercise of power and that the delegation does not violate the Constitution. The vast majority of executive actions are taken in exercise of such delegated powers, subject to check by judicial review for compliance with the statutory standards and the Constitution. These actions fall into Justice Jackson s first grouping.

Second, the Executive may acquire customary authority by a systematic and consistent practice known to and not questioned by Congress. These actions fall into Justice Jackson s twilight zone grouping.

Third, the President, in her capacity as Commander in Chief, may act without express statutory authority in some circumstances, but dicta in The Steel Seizure Case suggest that the scope of her independent powers may depend on the de jure existence of a war, the locus of the actions, or their impact on constitutional rights and liberties, among other factors.

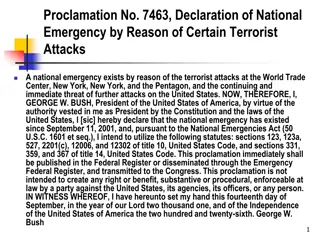

Unlike many constitutions, ours does not vest the head of state with general emergency powers. Instead, Congress may anticipate emergencies by delegating contingent emergency powers to the executive branch by statute. Even so, several Justices in The Steel Seizure Case speculated in dicta that the President might, after all, have some kind of inherent emergency powers depending on the gravity of the emergency.

Infrequently, the President acts in defiance of statutory limits or prohibitions, placing his action in Justice Jackson s third grouping. When branches collide, the Supreme Court has taken two approaches to declaring a winner. If the constitutional text expressly vests a power in a branch, the Court enforces that assignment without trying to balance the interests of the branches. But if the constitutional text is silent about the asserted power, then the Court engages in a balancing analysis: deciding whether the degree of intrusion on the President s powers caused by the statute is justified by an overriding need to promote objectives within Congress s constitutional authority.

Because declaring a winner in Justice Jacksons third grouping requires a court either to strike down a presidential action or to declare a statute unconstitutional, all three branches try mightily to avoid a collision. The President s lawyers push the limits of statutory construction to find some colorable statutory authority or to narrowly construe statutory limits. Congress looks the other way or acquiesces in some fashion. And the courts deploy a panoply of avoidance techniques, ranging from declining to reach the merits by invoking the standing, ripeness, state secrets, and political question doctrines, to avoiding the merits of the constitutional question by construing statutes (where possible) to sidestep the constitutional question.