The Importance of Breathing Exercises in Respiratory Management

Breathing exercises, also known as ventilatory training, play a crucial role in improving pulmonary status, enhancing endurance, and increasing overall functionality in daily activities. These exercises help retrain respiratory muscles, improve ventilation, reduce breathing effort, enhance gas exchange, and boost patient well-being. They are essential for managing acute and chronic pulmonary disorders, aiming to address various impairments and promote pulmonary health. The goals, indications, and guidelines for teaching breathing exercises are outlined in this comprehensive guide.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

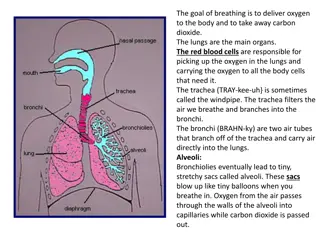

Also called as ventilatory training. An aspect of management to improve pulmonary status and to increase a patient s overall endurance and function during daily livingactivities. They are fundamental interventions for the preventionor comprehensive management of impairments related to acute or chronic pulmonarydisorders. Simply,Breathing exercises are designed to retrain the muscles of respiration, improve ventilation, lessen the work of breathing, and improve gaseous exchange and patient s overall function indaily livingactivities. Depending on a patient s underlying pathology and impairments, exercises to improve ventilation often are combined with medication, airway clearance, the use of respiratory therapy devices, and a graded exercise(aerobic conditioning)program.

Goals of Breathing Exercisesand Ventilatory MuscleTraining 1. 2. Improve or redistributeventilation. Increase the effectiveness of the cough mechanism andpromote airway clearance. Prevent postoperative pulmonarycomplications. Improve the strength, endurance, and coordination of the muscles ofventilation. Maintain or improve chest and thoracic spinemobility. Correct inefficient or abnormal breathing patterns and decrease the work ofbreathing. Promote relaxation and relievestress. Teach the patient how to deal with episodes ofdyspnea. Improve a patient s overall functional capacity for daily living, occupational, and recreational activities. 10. Aid in bronchial hygiene---Prevent accumulation of pulmonary secretions, mobilization of these secretions, and improve the cough mechanism. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9.

Indications of breathingexercises 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Cysticfibrosis Bronchiectasis Atelectasis Lungabscess Neuromuscular diseases Pneumonias in dependent lungregions. Acute or chronic lungdisease COPD For patients with a high spinal cord lesion/ Deficits in CNS: spinal cord injury, myopathies etc. Prophylactic care of preoperative patient with history of pulmonary problems After surgeries (thoracic or abdominalsurgery) Airway obstruction due to retainedsecretions. For patients who must remain in bed for an extended period oftime. As relaxation procedure. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14.

Guidelines for TeachingBreathing Exercises If possible, choose a quiet area for instruction in which you can interact with the patient with minimal distractions. Explain to the patient the aims and rationale of breathing exercises or ventilatory training specific to his or her particular impairments and functional limitations. Have the patient assume a comfortable, relaxed position and loosen restrictive clothing. Initially, a semi-Fowler s position with the head and trunk elevated approximately 45, is desirable. By supporting the head and trunk, flexing the hips and knees, and supporting the legs with a pillow, the abdominal muscles remain relaxed. Other positions, such as supine, sitting, or standing, may be used initially or as the patient progresses during treatment.

Observe and assess the patients spontaneousbreathing pattern while at rest and later withactivity. Determine whether ventilatory training isindicated. Establish a baseline for assessing changes, progress,and outcomes of intervention. If necessary, teach the patient relaxation techniques. This relaxes the muscles of the upper thorax, neck, and shoulders to minimize the use of the accessory musclesof ventilation. Pay particular attention to relaxation of the sternocleidomastoids, upper trapezius, andlevator scapulae muscles. Depending on the patient s underlying pathology and impairments, determine whether to emphasize the inspiratory or expiratory phase ofventilation. Demonstrate the desired breathing pattern to thepatient. Have the patient practice the correct breathing pattern ina variety of positions at rest and withactivity.

PRECAUTIONS: When teaching breathing exercises, be aware of thefollowing precautions: Never allow a patient to force expiration. Expiration should be relaxed or lightly controlled. Forced expiration only increases turbulence in the airways, leading to bronchospasm andincreased airway restriction. Do not allow a patient to take a highly prolonged expiration. This causes the patient to gasp with the next inspiration. Thepatient s breathing pattern then becomes irregular andinefficient. Do not allow the patient to initiate inspiration with the accessory musclesandtheupper chest.Advisethepatientthat theupper chest should be relatively quiet duringbreathing. Allowthepatienttoperform deepbreathing for onlythreeor four inspirations and expirations at a time to avoidhyperventilation. 1. 2. 3. 4.

CONTRAINDICATIONS: Increased ICP Unstable head or neck injury Active hemorrhage with hemodynamic instability or hemoptysis Recent spinal injury Empyma Bronchoplueral fistula Flail chest Uncontrolled hypertension Anticoagulation Rib or vertebral fractures or osteoporosis Acute asthma or tuberculosis Patients who have recently experienced a heart attack. Patients with skin grafts or spinal fusions will have undue stress placed on areas ofrepair.

Bony metastases, brittle bones, bronchial hemorrhage, and emphysema are contraindications for undue stress to the thoracic area. Verify that patient has not eaten for at least one hour. Severe Obesity Recent (within one hour) meal or tube feed Untreated pneumothorax Chest tubes.

TYPES OF BREATHINGEXERCISES: 1.Diaphragmaticbreathing 2.Pursed lipbreathing 3.Segmental breathing(costal expansion exercise) a)Apical breathing b)lateral costal expansion c)Posterior basalexpansion 4.Sustained maximal inspiration (deep breathing)

DIAPHRAGMATICBREATHING When the diaphragm is functioning effectively in its role as the primary muscle of inspiration, ventilation is efficient andthe oxygen consumption of the muscles of ventilation is low during relaxed (tidal) breathing. When a patient relies substantially onthe accessory muscles of inspiration, the mechanical work of breathing (oxygen consumption) increases and the efficiency of ventilationdecreases. Although the diaphragm controlsbreathing at an involuntary level, a patient with primary or secondary pulmonary dysfunction can be taught how tocontrol breathing by optimal use of thediaphragm and decreased use of accessorymuscles. The semireclining (as shown) andsemi- Fowler s positionsare comfortable, relaxed positions in whichto teach diaphragmaticbreathing.

GOALS OF DIAPHRAGMATICBREATHING: To improve the efficiency of ventilation andoxygenation Decrease the work ofbreathing Increase the excursion (descent or ascent) ofthe diaphragm Improve gas exchange andoxygenation. Diaphragmatic breathing exercises also are usedduring postural drainage to mobilize lungsecretions. Reduces work ofbreathing Reduces the incidence of post operativepulmonary complications Improveventilation Eliminates accessory muscleactivity Decrease respiratoryrate Increase tidalventilation Improve distribution ofventilation

PROCEDURE/TECHNIQUE: 1. Prepare the patient in a relaxed and comfortable position in which gravity assists the diaphragm, such as a semi- Fowler s position. 2. The patient initiates the breathing pattern with the accessory muscles of inspiration (shoulder and neck musclulature), start instruction by teaching the patient how to relax those muscles (shoulder rolls or shoulder shrugs coupled withrelaxation). 3. Diaphragmatic breathing enhance diaphragmatic descent during inspiration and diaphragmatic ascent during expiration 4. Physiotherapist assist diaphragmatic ascent by directing the patient to allow the abdomen to retract gradually during exhalation or by contracting abdominal muscles actively 5. Diaphragmatic descent is assisted by directing the patient to protract the abdomen gradually during inhalation.

6. Place your hand(s) on the rectus abdominis just below anterior costal margin. Ask the patient to breathe in slowly and deeply through the nose. Havethe patient keep the shoulders relaxed and upper chest quiet, allowing the abdomen to rise slightly. Then tell the patient to relax andexhale slowly throughthe mouth. Have the patient practice this three or four times and then rest. Do not allow the patient tohyperventilate. If the patient is having difficulty using the diaphragm during inspiration, have the patient inhale several times in succession through the nose by using a sniffing action This action usually facilitates the diaphragm. 10. To learn how to self-monitor this sequence, have the patient place his or her own hand below the anterior costal margin and feel the movement. The patient s hand should rise slightly during inspiration and fall during expiration. 11. After the patient understands and is able to control breathing using a diaphragmatic pattern, keeping the shoulders relaxed, practice diaphragmatic breathing in a variety of positions (sitting, standing) and during activity (walking, climbing stairs). 7. 8. 9.

RE EDUCATION OF DIAPHRAGM: As other skeletal muscles, diaphragm also shares the property of skeletal muscle Place the index and middle finger below the lower costal margin anteriorly in half lying position over the insertion of diaphragm (central tendon) At the end of expiration when diaphragm is relaxed, stretch stimulus is given to thediaphragm to elicit Stretch reflex of the diaphragm and patient is instructed to take breath in.

Resisted diaphragmaticbreathing Manual resistance by therapist over theabdomen Placing appropriate weight over abdomenin By slightly elevating the foot end of thebed *procedure- same as breathing ex *CONTRAINDICATIONS-SAME AS BREATHING

PURSED LIPBREATHING Pursed-lip breathing is a strategy that involves lightly pursing the lips together during controlled exhalation. USES OF PURSED LIP BREATHING/ INDICATIONS: This breathing pattern often is adopted spontaneously by patients with COPD to deal with episodes ofdyspnea. Improves ventilation Releases trapped air in the lungs Keeps the airways open longer and decreases the work of breathing Prolongs exhalation to slow the breathing rate Improves breathing patterns by moving old air out of the lungs and allowing for new air to enter thelungs Relieves shortness of breath Causes general relaxation

It can be applied: -as a 3-5 minutes rescue exercise or an Emergency Procedureto counteract acute exacerbations or dyspnea (shortage of air or breathlessness) in COPD and asthma. Pursed-lip breathing reduces hyperventilation-induced broncho- constriction. PRINCIPLE: Many therapists believe that gentle pursed-lip breathing and controlled expiration is a useful procedure, particularly to relieve dyspnea if it is performed appropriately. It is thought to keep airways open by creating back-pressure inthe airways. Studies suggest that pursed-lip breathing decreases the respiratory rate and the work of breathing (oxygenconsumption), increases the tidal volume, and improves exercisetolerance.

PRECAUTIONS: The use of forceful expiration during pursed-lip breathing must be avoided. Forceful expiration while the lips are pursed can increase the turbulence in the airways and cause further restriction of the smallbronchioles. Therefore, if a therapist elects to teach this breathing strategy, it is important to emphasize with the patient that expiration should be performed in a controlled manner but not forced. PROCEDURE/TECHNIQUE: Have the patient assume a comfortable position and relax as much as possible. Have the patient breathe in slowly and deeply through the nose and then breathe out gently through lightly pursed lips as if blowing on and bending the flame of a candle but not blowing it out. Explain to the patient that expiration must be relaxed and that contraction of the abdominals must be avoided. Place your hand over the patient s abdominal muscles to detect any contraction of the abdominals.

SEGMENTALBREATHING Performed on a segment of lung, or a sectionof chest wall that needs increased ventilation or movement. It s questionable whether a patient can betaught to expand localized areas of the lung while keeping other areasquiet. Hypoventilation does occur in certain areas ofthe lungs because of pain and muscle guarding after surgery, atelectasis andpneumonia. Therefore, it will be important to emphasize expansion of problems areas of the lungs and chest wall under certainconditions. USES/INDICATIONS: postthoracotomy, trauma to chestwall, pneumonia, post mastectomy scar, post chest radiation-fibrosis.

ADVANTAGES OF SEGMENTALBREATHING: Prevent accumulation of pleural fluid Prevent accumulation ofsecretions Decreases paradoxical breathing Decrease panic Improve chest mobility Lateral costalexpansion This is sometimes called lateral basal expansion and may be done unilaterally or bilaterally. The patient may be sitting or in a hook lyingposition. Place your hands along the lateral aspect of the lower ribs to fix the patient s attentionto the areas which movement is tooccur. Ask the patient to breathe out, and feel the rib cage move downward andinward. As the patient breathes out, place firm downward pressure into the ribs with the palms of your hands. Justprior to inspiration, apply a quick downward andinward stretch to the chest. This places a quick stretch on the external intercostals to facilitate their contraction. These muscles move the ribs outward andupward duringinspiration. Apply light manual resistance to the lower ribs to increase sensory awareness as the patient breathes in deeply and the chest expands and ribs flare. Then, as the patient breathes out, assist by gently squeezing the rib cage in a downward and inward direction.

Tellthepatient toexpandthelower ribs againstyour handas heor she breathes in. Apply gentle manual resistance to the lower rib area to increase sensory awarenessas thepatientbreathes inandthechest expandsandribs flare. Then,again,as thepatient breathes out,assistby gentlysqueezing therib cage in a down ward and inwarddirection. The patient may then be taught to perform the maneuver independently.He or She mayplacethehand(s) overtheribs or apply resistance usinga belt. Posterior basalexpansion Deep breathing emphasizing posterior basal expansion is important for the postsurgical patient who is confined to bed in a semireclining position for an extendedperiod of timebecause secretionsoftenaccumulateintheposterior segments of the lowerlobes. Havethepatient sit andlean forward ona pillow, slightlybendingthehips. Placeyour handsovertheposterioraspectofthelower ribs. Follow the same procedure as describedabove. Thisformof segmental breathingis importantfor thepost surgicalpatient who is confined to bed in a semi upright position for an extended period of time. Secretions oftenaccumulateinthe posteriorsegmentsofthelower lobes.

Belt exercises reinforce lateral costal breathing (A) by applying resistanceduring inspiration and (B) by assisting with pressure along the rib cageduring expiration.

Right middle lobe or lingula expansion Patient is sitting. Place your hands at either the right or the left side of the patient s chest, just below theaxilla. Follow the same procedure as described for lateral basal expansion. Apical expansion Patient in sitting position. Apply pressure (usually unilaterally) below the clavicle with the fingertips. This pattern is appropriate in an apical pneumothorax after a lobectomy. *Precautions-same as general

GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL BREATHING Glossopharynegal breathing is a means of increasing a patient sinspiratory capacity when thereis severe weakness of themusclesofinspiration. The first report of GPB was published by Dail in 1951in patients with poliomyelitisparalysis. It is a technique that is performed by using themuscles of mouth, cheeks, lips, tongue,soft palate,larynx andpharynx topiston bolusesof air intothelungs. The tongue is the main organ of this breathingtechnique. Thetongueis pushedupwardsandbackwards forcingthe air intothepharynx. Thelarynx opensandtheair passes intothetrachea whereit is trappedby closure oflarynx. This pistoning action is mechanism of eachgulp. Agulpis defined as bolusesof air projectedintothetracheaby pistoningaction of thetongue. INDICATIONS: Itis taughttopatientswho havedifficulty takingina deepbreath,for example, in preparation forcoughing. Itis used primarily by patients who are ventilator-dependent because of absent or incomplete innervation of the diaphragmas the result of a highcervical-level spinal cord lesion or other neuromusculardisorders.

Glossopharyngeal breathing can reduce ventilatordependence Also can be used as an emergency procedure when a malfunction of apatient s ventilatoroccur. Italsocanbe usedtoimprovetheforce(andthereforetheeffectiveness)ofa cough It is used to increase the volume of thevoice. Procedure Glossopharyngeal breathing involves taking several gulps of air, usually 6to 10 gulps in series, to pull air into the lungs when action of the inspiratory muscles isinadequate. After the patient takes several gulps of air, the mouth isclosed. Thetonguepushes theair back andtrapsitinthepharynx. Theair is thenforcedintothelungswhen theglottisis opened. Thisincreases thedepthof theinspirationandthepatient sinspiratoryand vitalcapacities

COUGHING An effective cough is necessary to eliminate respiratory obstructions and keep the lungs clear. Airway clearance is an important part of management of patients with acute or chronic respiratory conditions. The NormalCough Pump A cough may be reflexive or voluntary. When a person coughs, a series of actions occurs asfollows: Deep inspiration occurs-------Glottis closes------vocal cords tighten------ Abdominal muscles contract-------diaphragm elevates-------causing an increase in intrathoracic and intra-abdominal pressures-------Glottis opens-----Explosive expiration of air occurs. Under normal conditions, the cough pump is effective to the seventh generation of bronchi. (There are a total of 23 generations of bronchi in the tracheobronchial tree.) Ciliated epithelial cells are present up to the terminal bronchiole and raise secretions from the smaller to the larger airways in the absence of pathology.

Factors thatDecrease theEffectiveness oftheCough Mechanism and Cough Pump The effectiveness of the cough mechanism can be compromised for a number of reasons including the following: 1. Decreased inspiratory capacity 2. Inability to forcibly expel air 3. Decreased action of the cilia in the bronchial tree. 4. Increase in the amount or thickness of mucus. 1. Inspiratory capacity can be reduced because of: Pain due to acute lung disease Ribfracture Trauma to the chest Recent thoracic or abdominal surgery Weakness of the diaphragm or accessory muscles of inspiration as a result of a high spinal cord injury or neuropathic or myopathic disease Postoperatively, the respiratory center may be depressed as the result of general anesthesia, pain, or medication. Decreased inspiratory capacity:

2. A spinal cord injury above T12 and myopathic disease, such as muscular dystrophy,cause weakness ofthe abdominalmuscles,which are vital fora strongcough. Excessive fatigue as the result of criticalillness A chest wall or abdominal incision causingpain A patient who has had a tracheostomy, even when the tracheostomy siteis covered. Inability to forcibly expelair: The following factors contribute to a weakcough: 3. Physical interventions such as general anesthesia andintubation Pathologies such as COPD including chronicbronchitis Smoking also depresses the action of thecilia. Decreased action of the cilia in the bronchialtree: Action of the ciliated cells may be compromised becauseof: 4. Pathologies (e.g., cystic fibrosis, chronic bronchitis) and pulmonaryinfections (e.g.,pneumonia) Intubationirriatesthelumenoftheairways andcauses increasedmucus production Dehydration thickensmucus. Increase in the amount or thickness ofmucus: Occursin:

Teaching anEffective Cough Because an effective cough is an integral component of airway clearance, a patient must be taught the importance of an effective cough, how to produce an efficient and controlled voluntary cough, and when tocough. The following sequence and procedures are used when teaching aneffective cough. Assess the patient s voluntary or reflexive cough. Have the patient assume a relaxed, comfortable position for deep breathing and coughing. Sitting or leaning forward usually is the best position forcoughing. The patient s neck should be slightly flexed to make coughing morecomfortable. Teach the patient controlled diaphragmatic breathing, emphasizing deepinspirations. Demonstrate a sharp, deep, double cough. Demonstrate the proper muscle action of coughing (contraction of the abdominals). Have the patient place the hands on the abdomen and make three huffs with expiration to feel the contraction of the abdominals. Have the patient practice making a K sound to experience tightening the vocal cords, closing the glottis, and contracting the abdominals. When the patient has put these actions together, instruct the patient to take a deep but relaxed inspiration, followed by a sharp doublecough. The second cough during a single expiration is usually moreproductive. Use an abdominal binder or glossopharyngeal breathing in selected patients with inspiratory or abdominal muscle weakness to enhance the cough, ifnecessary. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10.

PrecautionsforTeachingan EffectiveCough Never allow a patientto gaspinair,because thisincreases thework (energy expenditure) of breathing, causing the patient to fatigue more easily. It also increases turbulence and resistance in the airways, possibly leading to increased bronchospasm and further constriction ofairways. A gasping action also may push mucus or a foreign object deep intoair passages. Avoid uncontrolled coughing spasms (paroxysmalcoughing). Avoid forceful coughing if a patient has a history of a cerebrovascularaccident or an aneurysm. Have these patients huff several times to clear the airways, rather thancough. Besurethatthepatient coughswhileina somewhaterect or side-lyingposture. AdditionalTechniquestoFacilitatea Coughand ImproveAirway Clearance To maximize airway clearance, several techniques can be used to stimulate a strongercough,makecoughingmorecomfortable or improvetheclearance of secretions. Manual-AssistedCough If a patient has abdominal weakness (e.g., as the result of a mid-thoracic or cervical spinal cord injury), manual pressure on the abdominal area assists in developing greater intra abdominal pressure for a more forcefulcough. Manual

Therapist-Assisted Techniques With the patient in a supine or semireclining position, the therapist places the heel of one hand on the patient s abdomen at the epigastric area just distal to the xiphoid process. The other hand is placed on top of the first, keeping the fingers open or interlocking them After the patient inhales as deeply as possible,the therapist manually assists the patient as he or she attempts to cough. The abdomen is compressed with an inward and upward force, which pushes the diaphragm upward to cause a more forceful and effective cough. This same maneuver can be performed with the patient in a chair The therapist or family member can stand in back of the patient and apply manual pressure during expiration. P R E C A U T I O N : Avoid direct pressure on the xiphoid process during themaneuver. Self-Assisted Technique While in a sitting position, the patient crosses the arms across the abdomen or places the interlocked hands below the xiphoid process After a deep inspiration, the patient pushes inward and upward on the abdomen with the wrists or forearms and simultaneously leans forward while attempting to cough.