History of Residential Schools in Canada

Learn about the disturbing history of residential schools in Canada where Indigenous children were forcibly taken from their families to assimilate them into the dominant culture. These schools operated from the early 1830s until 1996, causing deep trauma and lasting impacts on generations of Indigenous peoples. Explore the significant events and policies surrounding these institutions, such as the Indian Act amendments and the experiences of survivors from St. John's Indian Residential School in Wabasca, AB.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

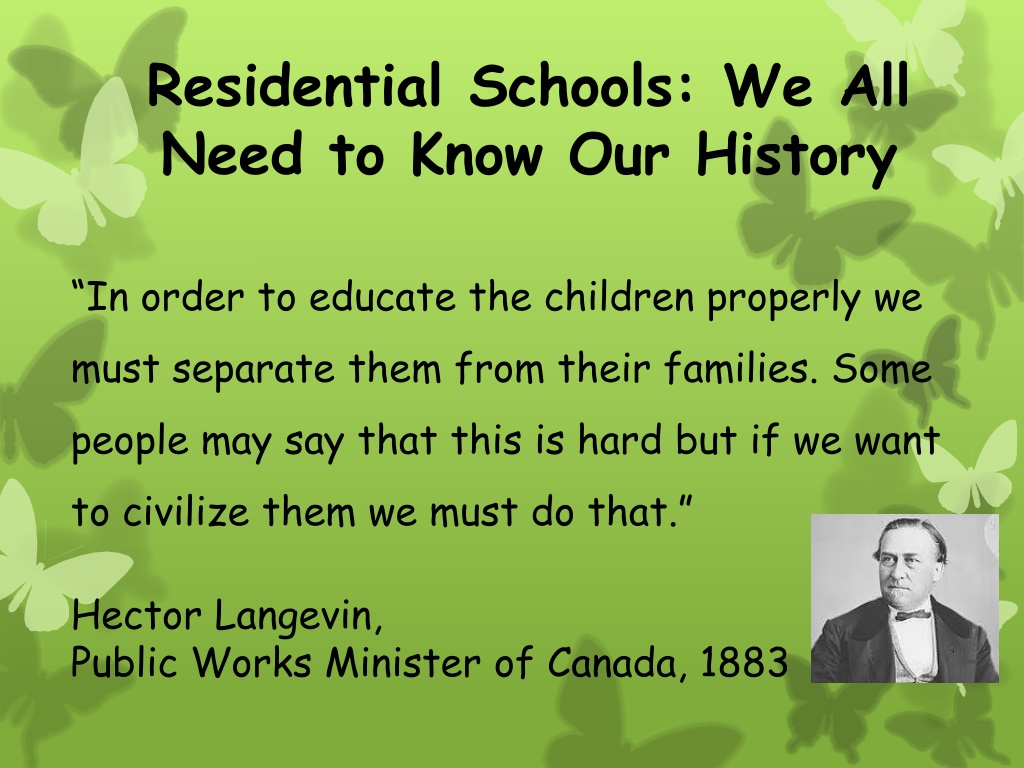

Residential Schools: We All Need to Know Our History In order to educate the children properly we must separate them from their families. Some people may say that this is hard but if we want to civilize them we must do that. Hector Langevin, Public Works Minister of Canada, 1883

Residential Schools in Canada From the early 1830s to 1996, thousands of First Nation, Inuit and M tis children were forced to attend residential schools in an attempt to assimilate them into the dominant culture. Over 150,000 children, some as young as four years old, attended the government-funded and church-run residential schools. It is estimated there are 80,000 residential school Survivors alive today.

The Indian Act was amended in 1884 to make boarding school mandatory for all Aboriginal children between the ages of six and fifteen. Parents who did not co-operate would be fined or sent to prison.

St. Johns Indian Residential School Wabasca, AB

Important Dates for St. Johns Residential School: 1894: St. John s Mission established at Wabasca by Church Missionary Society (CMS). Mission house accommodates 6 boarders. 1896: Residential enrolment increases to 12. 1898 1899: School temporarily closed for much of this period due to lack of missionary funds and unwillingness by government to assist school, which is in a non-treaty area. 1899: Aug. Wabasca area bands (Bigstone Cree Nation) adhere to Treaty 8, assuring creation of future reserve and government support of schools.

http://www.wherearethechildren.ca/en/exhibit/images/leavinghome/rd_31.jpghttp://www.wherearethechildren.ca/en/exhibit/images/leavinghome/rd_31.jpg A mother brings her children to the St. John Boarding School, Wabasca, Alberta, date unknown Photographer: The Anglican Church of Canada, The General Synod Archives, GS-75-103-S8- 242

1902: Government recognizes St. Johns Mission Wapuskaw School as a boarding school and implements program of annual per capita grants based on authorized pupilage of 15. 1903: Nov. Fire destroys residential school building. Students stay in the church until replacement building is completed the following year. The start on construction for this new school (funded by the church) in 1903 is often taken as the founding date for St. John s Indian Residential School. Farming begins in earnest on a cleared portion of the 45 acres of heavily forested, church owned land.

1910: Authorized pupilage increases to 25. 1911: Operating agreement signed between Indian Affairs and Diocese of Athabasca, outlining funding formula, standards for student enrolment and Church s obligation to maintain facilities and provide staff. 1940s 1950s Wabasca School suffers from chronic staff shortage, due in part to wartime labour shortage, competition from public schools offering better wages, and general inability of the Church to attract staff to this remote school.

Students at St. John's Residential School in Wabasca, Alberta (1945)

1945: Jan. 1 Fire destroys main dormitory building, requiring students to be temporarily housed in makeshift quarters in other mission and settlement buildings. 1949: Dec. 1 Government opens new dormitory block with capacity for 60 students. 1956: Expansion of main residential school building consolidates all school activities classrooms, dormitories and staff rooms under one roof. Previously, the school and residence were about 2 km apart.

1966: St. Johns School and Student Residence closes. Students are transferred to secular day schools (formerly Catholic) in nearby Desmarais, managed by NSD. Those eligible to attend senior high school must leave Wabasca and board with families in larger centres such as Edmonton.

A Survivors Story Peerless Lake resident, Elder David Starr has no fond memories of residential schools after living in one at Wabasca some 55 years ago. David was born at long Lake about five km north of Peerless Lake in 1930. Located in northern Alberta, 250 km north of Slave Lake, the tiny community of 430 people once had no contact with the outside world.

When David's parents decided to separate, he and his two sisters were sent to the St. John's Anglican Church residential school at Wabasca. His two sisters never survived the school. "They both died before their 16th birthdays. They died because of a lack of medical attention. It left me alone at the school," David recalled. Rocky Woodward, Windspeaker Correspondent, Peerless Lake Alta. Volume: 7 Issue: 26 Year: 1990

Dr. Peter Bryce, Medical Inspector for the Department of Indian Affairs After assessing the health situation at residential schools in 1909, Dr. Bryce calculated death rates among school age children as ranging from 35% and 60%. Even after Dr. Bryce s report to the government, many children like David Starr s sisters, would continue to die from diseases, like tuberculosis.

Duncan Campbell Scott, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Although other people in addition to Dr. Bryce reported the unhealthy conditions in residential schools, Duncan Campbell Scott ignored these findings. He also terminated the position of Medical Inspector. The conditions in residential schools would not improve.

Other Children Lost at St. Johns Residential School St. John's IRS has nearly a full page of documents listed in a report relating to a cemetery and grave. Three entries for 1961 note that work was undertaken in the cemetery to clean up brush and paint crosses. According to the May 26 entry, the principal sent word that he would like to have people who could tell him the names of those buried there to come and show him the graves so they could be marked. Snow falls on gravesites in the Wabasca Cemetery. (Ken Armstrong for The Globe and Mail, 2008)

One survivor interviewed has a brother buried in the now neatly-kept cemetery that is located near the Anglican church, which operated St. John's IRS. "I remember where my brother was buried, but the cross that was there is gone and the cross that is there now isn't really where it should be because that's not where he is." The survivor notes that triangular boxes were used to cover some graves and crosses marked other graves. "A lot of these were taken away and from there we're not sure if the cross there is where the person was buried." Reference: Alberta Sweetgrass (November 1, 2008) Article Author: Shari Narine

Response from the Anglican Church I am not able to give you an answer, sadly, to your question. I am not aware of any deaths at St John s school. However, considering the available medical care of the era, lack of vaccinations, etc., there is a reasonable probability that some students or staff would have contracted some illness and that some may have died.

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (2011) Indian Residential Schools tried to make Aboriginal children talk, dress, think and act like non-Aboriginal Canadians. At the time, the government and churches believed that this was the right thing to do. Today, we know it was not. The last Indian Residential School was closed in 1996. On June 11, 2008, the Prime Minister of Canada apologized to all Aboriginal children who were sent to these schools for the many bad things that happened to many of them. Several of the churches that were a part of this system have also said they are sorry.

The Journey Toward Truth and Reconciliation Many former students have shared stories of their time at Indian Residential Schools to help all Canadians understand what happened and to help themselves heal and forgive. Today, healing initiatives are taking place in every region of the country. Sharing circles, healing circles, smudging, Sundances, the Potlatch, Pow-wows, and many other ceremonies have been revived in the last few decades. Reconnecting with culture provides an empowering focus in life. People who have a strong sense of their culture have a strong sense of self.

Dialogue Begins Healing for Residential School Survivors Dolphus Yellowdirt (far right) points out a photo to wife Eva and Gordon Burnstick at the Indian Residential Schools Healing Dialogue held in Edmonton March 12 and 13. Dolphus attended Ermineskin residential school, while Burnstick attended St. Martin s residential school in Desmarais. Both men are from Alexander First Nation. (Photo: Shari Narine)