Gene Regulation Through Lecture 9 at Stanford

Dive into the intricate world of gene regulation with Lecture 9 of CS273A at Stanford University. Explore the mechanisms and complexities of how genes are controlled, with a focus on transcriptional regulation. The lecture covers topics such as genetic switches, transcription factors, and regulatory sequences, providing valuable insights into the functioning of genes within cells.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

CS273A Lecture 9: Gene Regulation II 1 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Announcements http://cs273a.stanford.edu/ o Lecture slides, problem sets, etc. Course communications via Piazza o Auditors please sign up too PS1 due this Wednesday (10/26). 2 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

TTATATTGAATTTTCAAAAATTCTTACTTTTTTTTTGGATGGACGCAAAGAAGTTTAATAATCATATTACATGGCATTACCACCATATATTATATTGAATTTTCAAAAATTCTTACTTTTTTTTTGGATGGACGCAAAGAAGTTTAATAATCATATTACATGGCATTACCACCATATA CATATCCATATCTAATCTTACTTATATGTTGTGGAAATGTAAAGAGCCCCATTATCTTAGCCTAAAAAAACCTTCTCTTTGGAACTTTC AGTAATACGCTTAACTGCTCATTGCTATATTGAAGTACGGATTAGAAGCCGCCGAGCGGGCGACAGCCCTCCGACGGAAGACTCTCCTC CGTGCGTCCTCGTCTTCACCGGTCGCGTTCCTGAAACGCAGATGTGCCTCGCGCCGCACTGCTCCGAACAATAAAGATTCTACAATACT AGCTTTTATGGTTATGAAGAGGAAAAATTGGCAGTAACCTGGCCCCACAAACCTTCAAATTAACGAATCAAATTAACAACCATAGGATG ATAATGCGATTAGTTTTTTAGCCTTATTTCTGGGGTAATTAATCAGCGAAGCGATGATTTTTGATCTATTAACAGATATATAAATGGAA AAGCTGCATAACCACTTTAACTAATACTTTCAACATTTTCAGTTTGTATTACTTCTTATTCAAATGTCATAAAAGTATCAACAAAAAAT TGTTAATATACCTCTATACTTTAACGTCAAGGAGAAAAAACTATAATGACTAAATCTCATTCAGAAGAAGTGATTGTACCTGAGTTCAA TTCTAGCGCAAAGGAATTACCAAGACCATTGGCCGAAAAGTGCCCGAGCATAATTAAGAAATTTATAAGCGCTTATGATGCTAAACCGG ATTTTGTTGCTAGATCGCCTGGTAGAGTCAATCTAATTGGTGAACATATTGATTATTGTGACTTCTCGGTTTTACCTTTAGCTATTGAT TTTGATATGCTTTGCGCCGTCAAAGTTTTGAACGATGAGATTTCAAGTCTTAAAGCTATATCAGAGGGCTAAGCATGTGTATTCTGAAT CTTTAAGAGTCTTGAAGGCTGTGAAATTAATGACTACAGCGAGCTTTACTGCCGACGAAGACTTTTTCAAGCAATTTGGTGCCTTGATG AACGAGTCTCAAGCTTCTTGCGATAAACTTTACGAATGTTCTTGTCCAGAGATTGACAAAATTTGTTCCATTGCTTTGTCAAATGGATC ATATGGTTCCCGTTTGACCGGAGCTGGCTGGGGTGGTTGTACTGTTCACTTGGTTCCAGGGGGCCCAAATGGCAACATAGAAAAGGTAA AAGAAGCCCTTGCCAATGAGTTCTACAAGGTCAAGTACCCTAAGATCACTGATGCTGAGCTAGAAAATGCTATCATCGTCTCTAAACCA GCATTGGGCAGCTGTCTATATGAATTAGTCAAGTATACTTCTTTTTTTTACTTTGTTCAGAACAACTTCTCATTTTTTTCTACTCATAA CTTTAGCATCACAAAATACGCAATAATAACGAGTAGTAACACTTTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGA TAATGTTTTCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCCACAAACTTTAAAACACAGGGACAAAATTCTTGATATGCTTTCAACCGCTGCGTTTT GGATACCTATTCTTGACATGATATGACTACCATTTTGTTATTGTACGTGGGGCAGTTGACGTCTTATCATATGTCAAAGTTGCGAAGTT CTTGGCAAGTTGCCAACTGACGAGATGCAGTAACACTTTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATGT TTTCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCCACAAACTTTAAAACACAGGGACAAAATTCTTGATATGCTTTCAACCGCTGCGTTTTGGATAC CTATTCTTGACATGATATGACTACCATTTTGTTATTGTACGTGGGGCAGTTGACGTCTTATCATATGTCAAAGTCATTTGCGAAGTTCT TGGCAAGTTGCCAACTGACGAGATGCAGTTTCCTACGCATAATAAGAATAGGAGGGAATATCAAGCCAGACAATCTATCATTACATTTA AGCGGCTCTTCAAAAAGATTGAACTCTCGCCAACTTATGGAATCTTCCAATGAGACCTTTGCGCCAAATAATGTGGATTTGGAAAAAGA GTATAAGTCATCTCAGAGTAATATAACTACCGAAGTTTATGAGGCATCGAGCTTTGAAGAAAAAGTAAGCTCAGAAAAACCTCAATACA GCTCATTCTGGAAGAAAATCTATTATGAATATGTGGTCGTTGACAAATCAATCTTGGGTGTTTCTATTCTGGATTCATTTATGTACAAC CAGGACTTGAAGCCCGTCGAAAAAGAAAGGCGGGTTTGGTCCTGGTACAATTATTGTTACTTCTGGCTTGCTGAATGTTTCAATATCAA CACTTGGCAAATTGCAGCTACAGGTCTACAACTGGGTCTAAATTGGTGGCAGTGTTGGATAACAATTTGGATTGGGTACGGTTTCGTTG GTGCTTTTGTTGTTTTGGCCTCTAGAGTTGGATCTGCTTATCATTTGTCATTCCCTATATCATCTAGAGCATCATTCGGTATTTTCTTC TCTTTATGGCCCGTTATTAACAGAGTCGTCATGGCCATCGTTTGGTATAGTGTCCAAGCTTATATTGCGGCAACTCCCGTATCATTAAT GCTGAAATCTATCTTTGGAAAAGATTTACAATGATTGTACGTGGGGCAGTTGACGTCTTATCATATGTCAAAGTCATTTGCGAAGTTCT TGGCAAGTTGCCAACTGACGAGATGCAGTAACACTTTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATGTTT TCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCCACAAACTTTAAAACACAGGGACAAAATTCTTGATATGCTTTCAACCGCTGCGTTTTGGATACCT ATTCTTGACATGATATGACTACCATTTTGTTATTGTTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATGTTT TCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCCTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATGTTTTCAATGTAAGA GATTTCGATTATCCTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATGTTTTCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTA TCCTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATGTTTTCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCCTTATAGTT CATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATGTTTTCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCCTTATAGTTCATACATGCTT CAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATGTTTTCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCCTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAA 3 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17] TAAATGATTGTATGATAATGTTTTCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCCTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGT ATGATAATGTTTTCAATGTAAGAGATTTCGATTATCTTATAGTTCATACATGCTTCAACTACTTAATAAATGATTGTATGATAATAAAG

Genes = coding + non-coding long non-coding RNA microRNA rRNA, snRNA, snoRNA 4

Coding and non-coding gene production The cell is constantly making new proteins and ncRNAs. To change its behavior a cell can change the repertoire of genes and ncRNAs it makes. These perform their function for a while, And are then degraded. Newly made coding and non coding gene products take their place. The picture within a cell is constantly refreshing . 5 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Cell differentiation To change its behavior a cell can change the repertoire of genes and ncRNAs it makes. That is exactly what happens when cells differentiate during development from stem cells to their different final fates. 6 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Cell differentiation To change its behavior a cell can change the repertoire of genes and ncRNAs it makes. But how? 7 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Closing the loop Some proteins and non coding RNAs go back to bind DNA near genes, turning these genes on and off. 8 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Genes & Gene Regulation Gene = genomic substring that encodes HOW to make a protein (or ncRNA). Genomic switch = genomic substring that encodes WHEN, WHERE & HOW MUCH of a protein to make. [0,1,1,1] B H Gene Gene H N Gene N Gene B [1,0,0,1] [1,1,0,0] 9 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transcription Regulation Conceptually simple: 1. The machine that transcribes ( RNA polymerase ) 2. All kinds of proteins and ncRNAs that bind to DNA and to each other to attract or repel the RNA polymerase ( transcription associated factors ). 3. DNA accessibility making DNA stretches in/accessible to the RNA polymerase and/or transcription associated factors by un/wrapping them around nucleosomes. (Distinguish DNA patterns from proteins they interact with) 10 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Promoters 11 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Enhancers 12 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

One nice hypothetical example requires active enhancers to function functions independently of enhancers 13 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Terminology Gene regulatory domain: the full repertoire of enhancers that affect the expression of a (protein coding or non-coding) gene, at some cells under some condition. Gene regulatory domains do not have to be contiguous in genome sequence. Neither are they disjoint: One or more enhancers may well affect the expression of multiple genes (at the same or different times). promoter TSS enhancers for different contexts 14 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Imagine a giant state machine Transcription factors bind DNA, turn on or off different promoters and enhancers, which in-turn turn on or off different genes, some of which may themselves be transcription factors, which again changes the presence of TFs in the cell, the state of active promoters/enhancers etc. Proteins DNA transcription factor binding site Gene DNA 15 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Signal Transduction: distributed computing Everything we discussed so far happens within the cell. But cells talk to each other, copiously. 16 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Enhancers as Integrators IF the cell is part of a certain tissue AND receives a certain signal THEN turn Gene ON Gene 17 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

The State Space Discrete, but very very large. All states served by same genome(!) 1012 cells 1 cell 18 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transcription Activation: Some measurements and observations 19 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transcription Factor Binding Sites (TFBS) An antibody is a large Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as bacteria. Antibodies can be raised that instead recognize specific transcription factors. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-seq): Take DNA (region or whole genome) bound by TFs, crosslink DNA-TFs, shear DNA, select DNA fragments bound by TF of interest using antibody, get rid of TF and antibody, sequence pool of DNA. Obtain genomic regions bound by TF. 20 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

ChIP-seq Position Weight Matrix Computational challenge: The sequenced DNA fragments are 200-500bp. In each is one or more instance of the 6-20bp motif. Find it 21 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transfections As far as we ve seen, enhancers work the same irrespective of distance (or orientation) to TSS, or identity of target gene. enhancer reporter gene minimal promoter in cellular context of choice Which enhancers work in what contexts? What if you mutate enhancer bases (disrupt or introduce binding sites) and run the experiment again? What if you co-transfect a TF you think binds to this enhancer? What if you instead add siRNA for that TF? 22 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transcription factors bind synergistically, often with preferred spacing Transcription factor complexes prefer specific spacings! Sox:1 bp:Pax Sox2 Pax6 Sox2 Pax6 0 5 10 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 {+2} Fold activation Sox:3 bp:Pax Sox2 Pax6 Sox2 Pax6 0 5 10 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 Fold activation Adapted from Kamach et al., Genes Dev, 2001 23 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

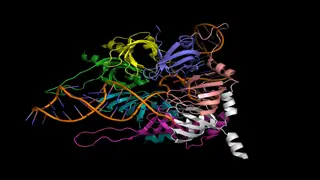

Strict spacing between binding sites is important for structural interactions 24 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Different Enhancer Structures 25 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Massively parallel reporter assays 26 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transgenics enhancer reporter gene minimal promoter Observe enhancer behavior in vivo. Qualitative (not quantitative) assay. Can section and stain to obtain more specific cell-type information. 27 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Gene Regulation: Enhancers are modular and additive neural tube brain limb Sall1 Temporal gene expression pattern equals sum of promoter and enhancers expression patterns. 28 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

BAC transgenics: necessity vs sufficiency You can take 100-200kb segments out of the genome, insert a reporter gene in place of gene X, and measure regulatory domain expression. You can then continue to delete or mutate individual enhancers. 29 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Genome Editing via CRISPR/Cas9 30 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Chromosome conformation capture (3C) People are also developing methods to detect when two genomic regions far in sequence are in fact interacting in space. Ultimately this will allow to determine experimentally the regulatory domain of each gene (likely condition dependent). 31 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

4C example result (in a single biological context) TSS probe Irreproducible peaks 32 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transcription Activation Terminology: RNA polymerase Transcription Factor Transcription Factor Binding Site Promoter Enhancer Gene Regulatory Domain TF DNA 33 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Enhancer Prediction How do TFs sum together to provide the activity of an enhancer? A network of genes? 34 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

The cis-regulatory code Given a sequence of DNA predict: Is it an enhancer? Ie, can it drive gene expression? If so, in which cells? At which times? Driven by which transcription factor binding sites? Given a set of different enhancers driving expression in the same population of cells: Do they share any logic? If so what is it? Can you generalize this logic to find new enhancers? 35 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transcription Regulation is not just about activation 36 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transcriptional Repression An equally important but less visible part of transcription (tx) regulation is transcriptional repression (that lowers/ablates tx output). Transcription factors can bind key genomic sites, preventing/repelling the binding of The RNA polymerase machinery Activating transcription factors (including via competitive binding) Some transcription factors have stereotypical roles as activators or repressors. Likely many can do both (in different contexts). DNA can be bent into 3D shape preventing enhancer promoter interactions. Activator and co-activator proteins can be modified into inactive states. Note: repressor thus can relate to specific DNA sequences or proteins. 37 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Insulators Insulators are DNA sequences that when placed between target gene and enhancer prevent enhancer from acting on the gene. The handful known insulators contain binding sites for a specific DNA binding protein (CTCF) that is involved in DNA 3D conformation. However, CTCF fulfills additional roles besides insulation. I.e, the presence of a CTCF site does not ensure that a genomic region acts as an insulator. TSS2 TSS1 Insulator 38 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Transcription & its regulation happen in open chromatin 39 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Nucleosomes, Histones, Transcription Chromatin / Proteins Genome packaging provides a critical layer of gene regulation. DNA / Proteins 40 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Gene Activation / Repression via Chromatin Remodeling A dedicated machinery opens and closes chromatin. Interactions with this machinery turn genes and/or gene regulatory regions like enhancers and repressors on or off (by making the genomic DNA in/accessible) 41 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Insulators revisited Insulators are DNA sequences that when placed between target gene and enhancer prevent enhancer from acting on the gene. Known insulators contain binding sites for a specific DNA binding protein (CTCF) that is involved in DNA 3D conformation. However, CTCF fulfills additional roles besides insulation. I.e, the presence of a CTCF site does not ensure that a genomic region acts as an insulator. TSS2 TSS1 Insulator 42 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Epigenomics The histone code 43 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Histone Tails, Histone Marks DNA is wrapped around nucleosomes. Nucleosomes are made of histones. Histones have free tails. Residues in the tails are modified in specific patterns in conjunction with specific gene regulation activity. 44 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Histone Mark Correlation Examples Active gene promoters are marked by H3K4me3 Silenced gene promoters are marked by H3K27me3 p300, a protein component of many active enhancers acetylates H3k27Ac. 45 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Measuring these different states Note that the DNA itself doesn t change. We sequence different portions of it that are currently in different states (bound by a TF, wrapped around a nucleosome etc.) 46 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Epigenomics: study all these marks genomewide Translate observations into current genome state. 47 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Obtain a network of all active genes & DNA Ridicilogram Now what? (to be revisited) 48 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Histone Code Hypothesis Histone modifications serve to recruit other proteins by specific recognition of the modified histone via protein domains specialized for such purposes, rather than through simply stabilizing or destabilizing the interaction between histone and the underlying DNA. histone modification: writer eraser reader 49 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]

Epigenomics is not Epigenetics Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression or cellular phenotype, caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence There are objections to the use of the term epigenetic to describe chemical modification of histone, since it remains unknown whether or not these modifications are heritable. 50 http://cs273a.stanford.edu [Bejerano Fall16/17]