Customer-Employee Substitution: Evidence from Gasoline Stations

Provocative paper explores how customers may substitute for workers in tasks difficult to automate, leading to worker displacement and inflated productivity levels. The study focuses on gas stations, estimating a considerable impact on attendant employment and productivity growth. Challenges in measurement and implications for broader retail are discussed, emphasizing the need for robust analysis and considerations of service variations.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

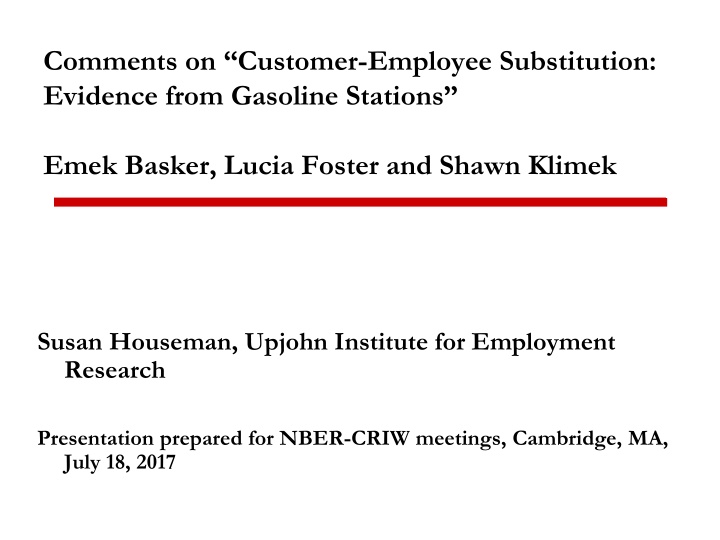

Comments on Customer-Employee Substitution: Evidence from Gasoline Stations Emek Basker, Lucia Foster and Shawn Klimek Susan Houseman, Upjohn Institute for Employment Research Presentation prepared for NBER-CRIW meetings, Cambridge, MA, July 18, 2017

Overview Provocative paper on important topic: Customers may substitute for workers in tasks that are manual, cognitively simple, but difficult to automate Can result in sizable worker displacement Estimated one-third fewer attendants in gas stations Customer-employee substitution can significantly inflate measured productivity levels/growth Back-of-the-envelop estimates: productivity growth inflated by 12.5% from 1977-1992 Divide comments into 3 areas: Empirical work on gasoline stations Broader measurement challenge of customer-employee substitution in retail Analogy to measuring labor productivity when tasks outsourced o o o o o o

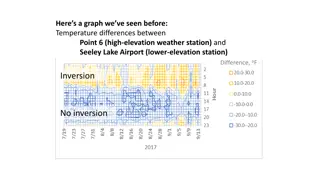

Current prevalence of gas station attendants in states with and without bans Automotive and watercraft service attendants as percent all gas station employees, by state, May 2016 42.1 24.2 18.9 5.6 5.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 0.9 0.9 2.1 2.3 2.5 Source: BLS, Occupational Employment Statistics Program If gas station production function does not systematically differ across states, implies full service stations employ 24% (Oregon) to 42% (NJ) more workers.

Effects of customer-employee substitution in gas stations Overall approach sensible given data limitations Endeavor to estimate effects on attendant employment, but lack occupation data Attempt to control for employment associated with ancillary services provided at gas station (repair, convenience store) Stations that are part of multi-unit or vertically integrated firm may have different employment composition e.g., some administrative services provided at headquarters. Controls likely incomplete/quantity gas sold or # self-service pumps could be picking up effects on other services Regression estimates sensitive to inclusion of control variables Estimated effects on attendant employment would be greater today, with pay-at-pump o o o o

Effects of customer-employee substitution in gas stations (cont.) More robustness checks on estimates of employment effects desirable Could exploit data from states with bans to estimate employment effects States with bans used in estimating back-of-envelop productivity effects Critical assumption that service provided by full and self-service gas stations, and so can be captured by gas sales, is debatable Full-service stations provide a bundled service Wash windshields, check oil Perform task of pumping gas o o o o o

Customer-employee substitution in retail Many rapidly developing cases in retail Scanner technology allows customers to check themselves out, replace cashiers On-line shopping, replace sales staff On-line banking, replace tellers Measuring effects on employment/worker displacement May not be easy because of data constraints Relatively straightforward conceptually Measuring effects on productivity trickier, raises complicated conceptual questions How do we measure customer labor input? How should wait time, time driving to the retail outlet be factored in? Even if customers performing some tasks, total time spent in purchases may be less o o o o o o o

Customer-employee substitution in retail: Alternative framing The service provided changes when customers substitute for employees Typically the case (even in self-service gas stations) Change, in principle, should be captured in quality-adjusted price of service From customers perspective, quality of the service may Deteriorate: e.g., requires greater effort to complete transaction, bundle of services provided less Improve: e.g., less time to complete transaction (wait time, transaction may be completed on-line), extended time when transaction may be completed o o o o

Analogy to labor productivity measurement with domestic and offshore outsourcing Contract company or independent contractors domestic or foreign substituted for a company s employees Rise in imported intermediates, services trade Some evidence suggests recent rise in domestic outsourcing (e.g. Katz and Krueger 2016; Abraham, Haltiwanger, Sandusky, Spletzer 2016) New technologies e.g., mobile apps, online platforms likely will expand scope for outsourcing As in customer-employee substitution, outsourcing results in a mechanical increase in labor productivity when output concept is gross (revenue) or sectoral output (i.e., not value-added) Micro studies that measure labor productivity = Revenue/L may be capturing differences across firms/establishments in degree of outsourcing, not true productivity differences Dey, Houseman, Polivka (2017) estimate large biases in BLS manufacturing labor productivity measures from outsourcing to temp services: depressed during downturns, inflated during expansions (0.5 from 2009-2015) o o o o o

Outsourcing effects on productivity measures MFP and labor productivity measured using value-added concept may be subject to sourcing substitution bias Outsourcing decision may be driven by lower (quality-adjusted) contractor prices/wages Even if value of inputs correctly measured, price deflators will not pick up price drops (Diewert and Nakamura 2010, Houseman et al. 2011, Reinsdorf and Yuskavage 2013) Data needs Growth/prospective future growth in outsourcing underscores need for better data on inputs/supply chains This paper points to possible need for data on customer inputs o o o o

![Read⚡ebook✔[PDF] Linking the Space Shuttle and Space Stations: Early Docking Te](/thumb/21519/read-ebook-pdf-linking-the-space-shuttle-and-space-stations-early-docking-te.jpg)