Stories of Village Life and Silk Production in the 1930s

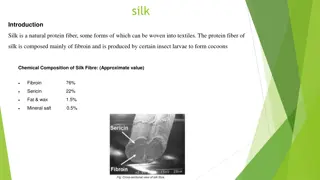

The works "Village Trilogy" by Mao Dun and "Salt" by Kang Kyeong-ae provide a glimpse into the rural life of the 1930s. The excerpt describes the tender care given to silkworms in the production of silk, highlighting the intricate details and struggles faced in this industry during that era.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Mao Dun, Village Trilogy (1932-33) Kang Kyeong-ae, Salt (1934)

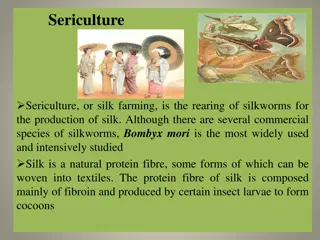

Bombyx mori By the time the old man ordered another thirty loads, and the first ten were delivered, the sturdy little darlings had gone hungry for half an hour. Putting forth their pointed little mouths, they swayed from side to side, searching for food. Daughter-in-law s heart had ached to see them. When the leaves were finally spread in the trays, the silkworm shed at once resounded with a sibilant crunching, so noisy it drowned out conversation. (29)