Weighting Strategies for Disaggregated Racial-Ethnic Data

Delve into the importance of weighting strategies for disaggregated racial-ethnic data in health policy research. Learn about the purpose of weighting, considerations, and when weights are unnecessary. Discover how survey weights ensure the representativeness and generalizability of data to target populations.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH National Network of Health Surveys Workshop Series WEIGHTING STRATEGIES FOR DISAGGREGATED RACIAL-ETHNIC DATA Tara Becker, PhD; Brian Wells, PhD; Ninez Ponce, PhD, MPP UCLA Center for Health Policy Research healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Outline of what we will cover Purpose of weighting Limitations of Weighting Weighting Considerations Benchmark Population Weighting Dimensions Coding of Race-ethnicity healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Why Is a Weighting Session Included In Data Disaggregation Series? Granular collection Granular tabulation Survey weights? Population Estimates healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH THE PURPOSE OF WEIGHTING healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Why do we weight survey data? Weights help us to reflect the complexities of sample design Weights are used for bias reduction Weighting ensures that: Data is representative of the target population Estimates will be generalizable to the target population healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH When are weights unnecessary? When all of these conditions hold: All members of target population have equal probability of appearing on list from which sample is drawn Participants are randomly sampled with equal probability Participants have equal probability of responding The resulting sample of respondents is a simple random sample that is representative of the full population healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Why we need survey weights Weights are used when the sample or respondent distribution is not aligned with the population distribution Can be attributed to any transition from the population to the respondents Population Frame Frame Sample Sample Respondents healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Conditions that affect representativeness Sampling frame is incomplete or contains errors Unequal probability of being sampled Nonresponse error healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH General form of weights Most weights have three components Selection probabilities Adjustments for nonresponse of the sample Adjustments to the population for coverage, sampling, and nonresponse ???? ? = ????????? ??????????? ?????? ??????????? ?????????? ?????????? healthpolicy.ucla.edu

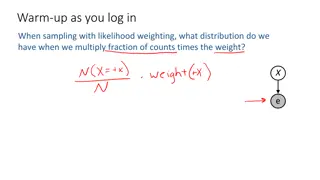

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Selection probabilities From a sampling frame, we select a scientific sample where all units have a nonzero probability of selection, or ?? ?? depends of the sample design The selection weight = the inverse of the selection probability or ??=1 ?? healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH A simple (random sample) example In a simple random sample, ??=? ? for all ? If N = 20, n = 5 5 20=1 4 So ??=1 ?? This means each person represents 4 people of the original population ??= 1 = 1 4= 4 healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Selection probabilities for complex designs Sample designs are rarely simple Sample designs can be complex due to: Stratification and/or clustering Multilevel or multistage Oversampling The selection probabilities (and thus selection weights) are a product of all stages of selection For example, selecting a census block in a census tract in a county healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Selection probability and data disaggregation If a study oversamples a small group, we want to account for this difference from the population. For example: Koreans make up about 1.3% of California s population Say we oversample so that the final sample has 2.6% Korean We want our final estimates to reflect the actual population of 1.3% and not mistake it for being 2.6% Larger sample helpful to disaggregate Koreans from other Asians, but don t want to over-represent Koreans in final estimates healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Sampling frame limitations If the sampling frame... Underrepresents a subpopulation within the target population, the sample will underrepresent that group Ex: landline frame will underrepresent Mexicans who are more likely to own a cell phone Excludes a subpopulation, the sample will also exclude that group Ex: homeless or transient population in an address-based sample Covers more than the desired population, the sample will not reflect our population Ex: cell phone numbers from previous CA residents now living outside CA healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Adjusting for nonresponse Failure to measure information on each sampled unit Might be due to: Inability to contact or find unit Unit is uncooperative Unit is ineligible or unable to participate Nonresponse can be due to respondent characteristics or design choices healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Nonresponse and data disaggregation If a subgroup of interest responds to a survey at a lower (or higher) rate, we want to account for this difference. For example: Central Americans may be less likely to participate in surveys Maybe more resistant to participate out of fear (political climate) Maybe survey not available in Spanish or indigenous language If Central Americans have a 30% response rate and non-Central Americans have a 50% response rate, we need to account for this shortage in our final sample healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Limitation of sample-based adjustments Sample-based adjustments require knowing information about both respondents and nonrespondents Sampling frame often does not provide this kind of information If unable to account for nonresponse based on individual-level characteristics, these can be covered through population- based adjustments healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Population-based adjustments Use information known about the population to make the respondent pool look like the population We obtain population characteristics from a benchmark, often from a census or a well-conducted survey Must also collect these characteristics in your survey healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Benchmark comparison example United States Decennial Census Census covering full population Complete coverage of US Conducted every 10 years Accuracy diminishes with each year Limited set of characteristics Age, gender, race/ethnicity American Community Survey Large, well-conducted survey Millions sampled every year Conducted annually Up-to-date counts and estimates Larger set of characteristics Age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, home ownership, health insurance, etc. healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Population adjustments and data disaggregation Regardless of what our final sample looks like, we want it to reflect the population. For example: We want our small sample of Cambodians (n 20) to reflect the approximately 87,000 Cambodians in California despite the difficulties in finding and completing interviews with Cambodians healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH What weighting does Standardizes the survey sample to make their characteristics match those of a relevant benchmark population Effectiveness of weighting depends on: Selection of the benchmark population Characteristics (dimensions) adjusted through weighting Sample size within subgroups healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH LIMITATIONS OF WEIGHTING healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Limitations of weighting The effectiveness of weighting is constrained by survey methodology and content Can only adjust for under/overrepresentation of a population, cannot make the sample representative of a missing subpopulation Small samples of subpopulations may not reflect the diversity within those populations even if the overall estimates for that subpopulation are representative Can only adjust based on characteristics that are measured Potential inflation in standard errors or variances healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Example: American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) Oversamples in the CA Health Interview Survey (CHIS) CHIS 2001 Sampling list developed with input from AIAN tribal organizations Large fraction from Indian Health Services clinic users Sampling stratified by urban/rural status CHIS 2012 Sampling list based on Indian Health Services clinic users Eligibility for Indian Health Services is based on membership in a federally recognized tribe healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Percent AIAN Enrolled in a Recognized Tribe 45% Unweighted 38.3% 40% Weighted 35% Percent of AIAN 30% 25% 19.0% 20% 13.3% 15% 11.9% 11.8% 11.4% 9.6% 9.5% 10% 5% 0% 2001 Oversample Source: California Health Interview Survey 2003 No Oversample 2012 Oversample 2013 No Oversample healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Percent AIAN with California Tribal Heritage Unweighted Weighted 65.9% 70% 65.7% 64.0% 62.4% 61.9% 60% 55.4% 50% 40% 30% 25.5% 20% 9.4% 8.6% 8.1% 7.6% 6.2% 10% 0% 2001 2003 No Oversample 2012 2001 2003 No Oversample 2012 Oversample Oversample Oversample Oversample % AIAN with CA Tribal Heritage % AIAN with Non-CA Tribal Heritage Source: California Health Interview Survey healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH WEIGHTING CONSIDERATIONS healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Benchmark Population healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Why do we need a benchmark population? Tells us what the population should look like absent Coverage bias in sampling frame Oversampling other design effects Nonresponse Bias can enter final sample in many ways and it s difficult to measure them all healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH How is the benchmark population used? Weighting process forces sample to look like the benchmark population on selected characteristics Any limitations of benchmark data will be imposed on final weights healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Choosing Benchmark Data Similarity to target population Considerations: Policy relevance Comparability to other data sources Quality of benchmark data Representativeness of relevant populations Availability of relevant characteristics healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Commonly Used Benchmark Data Decennial census U.S. Census Bureau intercensal population estimates American Community Survey (ACS) State government estimates (e.g., California Dept of Finance) Commercial population data (e.g., Claritas) healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Example: Coverage of AIANs in the ACS The ACS has historically undercounted AIANs (Luhan, 2014) The U.S. Office of Management and Budget defines AIAN as persons: having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America) and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment. American Community Survey undersamples from tribal lands ACS uses bridged-race estimates for weighting Multiracial individuals are redistributed into a single-race category healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Benchmark data from multiple sources Benchmark information can be drawn from multiple sources Sources may differ in small ways that create inconsistencies Must be brought in alignment with each other healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Example: CHIS Asian ethnic subgroup benchmarks Primary source (CA Dept of Finance [CA DOF] population estimates) does not include Asian ethnicities Asian ethnic subgroup distribution drawn from American Community Survey (ACS) Overall Asian population size differs between CA DOF and ACS ACS within-Asian ethnic subgroup distribution applied to CHIS Asian population estimates healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Example: 2012 California Race-Ethnicity 2012 American Community Survey 2012 CHIS Population 9,536,000 12,111,000 1,549,000 3,980,000 108,000 741,000 28,025,000 Percent 34.0% 43.2% 5.5% 14.2% 0.4% 2.6% 100% Population 9,517,000 12,094,000 1,566,000 3,846,000 122,000 652,000 27,796,000 Percent 34.2% 43.5% 5.6% 13.8% 0.4% 2.3% 100% Hispanic/Latino NH White NH Black NH Asian NH AI/AN Other NH Total Hispanic/Latino NH White NH Black NH Asian NH AI/AN Other NH Total healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Weighting Dimensions healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH What are Weighting Dimensions? The set of characteristics that are used to standardize the sample data After weighting, the respondents in the data will resemble benchmark(s) on these characteristics healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Choosing characteristics for weighting Characteristics associated with differential response rates Available in benchmark source and in data to be weighted High-quality measures with low complexity and rates of missing Examples: Gender Age Race-ethnicity Education Home ownership Urbanicity healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Defining dimensions Adjust for each characteristic independently Overall population distributions will match benchmark Adjust for characteristics within subgroups Ensure subgroup characteristics also match benchmark Appropriate when nonresponse patterns differ within groups Examples: Race-ethnicity within gender and/or age Race-ethnicity within U.S. state or other geographic region healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Sample size constraints Ideally, would like to make all subgroups representative Need enough respondents within subgroup With small number of respondents: Individual responses can be too influential in estimates Not enough variation to allow convergence across all dimensions Small samples may require collapsing categories, preventing adjustments for disaggregated categories healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Limitations of weighting dimensions Weighting dimensions might not fully account for differential nonparticipation Unmeasured characteristics associated with survey participation Lack of detail or precision in benchmark may restrict what can be adjusted Sample size constraints may prevent fully adjusting for or within disaggregated groups healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Coding Race-Ethnicity healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Measuring Race-Ethnicity Hispanic/Latino Separate dimension/measure Racial-ethnic category, i.e., Hispanic/Latino trumps all Treatment of multiracial respondents Multiracial category Bridged-race reassignment Indicators for race report Recode of other race reports Ethnic subgroups within racial groups healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Constraints on Coding Race-Ethnicity Oversamples of specific racial or ethnic groups Ability to match to benchmark population Sample size within racial-ethnic categories Collapsing categories with small numbers of respondents Collapsed categories will be adjusted to match benchmark as a group, not individually Ability to adjust for other characteristics within race-ethnicity Sample size (again!) healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Example: AIAN in Federal Survey Data Differences in: Data collection methodologies Non-response Benchmark data Inclusion of AIAN in weighting Importance of: Hispanic/Latino status Multiracial identity healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Weighting Characteristics: 6 Federal Surveys Survey American Community Survey Benchmark Data U.S. Census Bureau Bridged- Race Population Estimates Claritas Population Data AIAN in Weighting? Yes AIAN Subgroups Non-Hispanic AIAN Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey National Health Interview Survey In states with sufficient AIAN No Non-Hispanic single- race AIAN None American Community Survey one-year data file U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates American Community Survey one-year data file No None National Survey of Drug Use and Health Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health In states with sufficient AIAN No Single-race AIAN None healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Percent AIAN Adults in Federal Surveys 2.5% Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health 0.3% 0.7% 1.5% 2.3% National Survey of Drug Use and Health 0.5% 0.6% 1.2% National Health Interview Survey 0.6% 0.3% 0.7% 1.6% National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 0.6% 0.1% 1.0% 1.7% Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 1.1% 0.8% 0.9% 2.7% American Community Survey 0.6% 0.1% 0.7% 1.5% 0.0% Single-Race Latino AIAN 0.5% 1.0% 1.5% 2.0% Multiracial AIAN 2.5% 3.0% Single-Race Non-Latino AIAN healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH Example: AIAN Subgroups in CHIS Only one AIAN subgroup is included in the weighting dimensions: non-Hispanic single-race AIAN Hispanic/Latino AIAN included with Latino/Hispanic Non-Hispanic multiracial AIAN included with multiracial healthpolicy.ucla.edu

THE UCLA CENTER FOR HEALTH POLICY RESEARCH CHIS AIAN Population: Unweighted vs Weighted 2012 oversample vs 2013-2014 100% 36.1% 37.7% 80% 41.2% 53.0% 60% 23.2% 40% 47.2% 43.6% 21.6% 20% 39.0% 25.4% 16.7% 15.1% 0% 2012 OS: Unweighted 2013-2014: Unweighted 2012 OS: Weighted 2013-2014: Weighted Non-Latino Single Race Latino Single Race AIAN in combination healthpolicy.ucla.edu