Understanding Tuberculosis: Causes, Transmission, and Control

Tuberculosis, a major health issue in tropical countries, affects millions annually. Drug-resistant forms are on the rise, with pulmonary involvement crucial for transmission. Humans and cattle are reservoirs, with air-borne transmission. Host factors influence disease progression. Control strategies involve immunization, diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

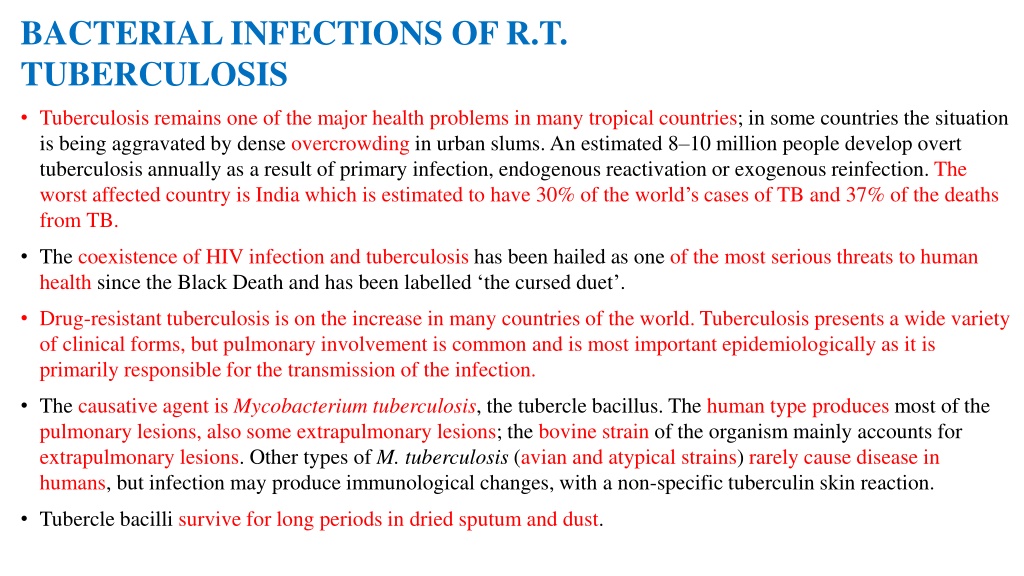

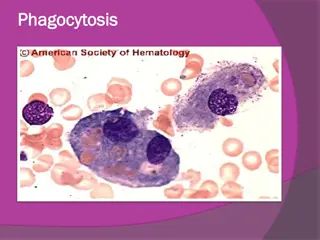

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS OF R.T. TUBERCULOSIS Tuberculosis remains one of the major health problems in many tropical countries; in some countries the situation is being aggravated by dense overcrowding in urban slums. An estimated 8 10 million people develop overt tuberculosis annually as a result of primary infection, endogenous reactivation or exogenous reinfection. The worst affected country is India which is estimated to have 30% of the world s cases of TB and 37% of the deaths from TB. The coexistence of HIV infection and tuberculosis has been hailed as one of the most serious threats to human health since the Black Death and has been labelled the cursed duet . Drug-resistant tuberculosis is on the increase in many countries of the world. Tuberculosis presents a wide variety of clinical forms, but pulmonary involvement is common and is most important epidemiologically as it is primarily responsible for the transmission of the infection. The causative agent is Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the tubercle bacillus. The human type produces most of the pulmonary lesions, also some extrapulmonary lesions; the bovine strain of the organism mainly accounts for extrapulmonary lesions. Other types of M. tuberculosis (avian and atypical strains) rarely cause disease in humans, but infection may produce immunological changes, with a non-specific tuberculin skin reaction. Tubercle bacilli survive for long periods in dried sputum and dust.

Epidemiology Tuberculosis has a worldwide distribution. Until recently, it was absent from a few isolated communities where the local populations are now showing widespread infections with severe manifestations on first contact with tuberculosis. RESERVOIR Humans are the reservoir of the human strain and patients with pulmonary infection constitute the main source of infection. The reservoir of the bovine strain is cattle, with infected milk and meat being the main sources of infection. TRANSMISSION Transmission of infection is mainly air-borne by droplets, droplet nuclei and dust; thus it is enhanced by overcrowding in poorly ventilated accommodation. Infection may also occur by ingestion, especially of contaminated milk and infected meat HOST FACTORS The host response is an important factor in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. A primary infection may heal, the host acquiring immunity in the process. In some cases the primary lesion progresses to produce extensive disease locally, or infection may disseminate to produce metastatic or military lesions. Lesions that are apparently healed may subsequently break down with reactivation of disease. Certain factors such as malnutrition, measles infection and HIV infection, use of corticosteroids and other debilitating conditions predispose to progression and reactivation of the disease.

Control In planning a programme for the control of tuberculosis, the entire population can be conveniently considered as falling into four groups: No previous exposure to tubercle bacilli they would require protection from infection. Healed primary infection they have some immunity but must be protected from reactivation of disease and reinfection. Diagnosed active disease they must have effective treatment and remain under supervision until they have recovered fully. Undiagnosed active disease without treatment the disease may progress with further irreversible damage. As potential sources of infection, they constitute a danger to the community. The control of tuberculosis can be considered at the following levels of prevention: general health promotion; specific protection active immunization, chemoprophylaxis, control of animal reservoir; early diagnosis and treatment; limitation of disability; rehabilitation; surveillance.

GENERAL HEALTH PROMOTION Improvement in housing (good ventilation, avoidance of overcrowding) will reduce the chances of air-borne infections. Health education should be directed at producing better personal habits with regard to spitting and coughing. Good nutrition enhances host immunity. SPECIFIC PROTECTION Three measures are available: (i)active immunization with BCG (Bacille Calmette Guerin);(ii)chemoprophylaxis; and (iii) control of animal tuberculosis. BCG vaccination This vaccine contains live attenuated tubercle bacilli of the bovine strain. It may be administered intradermally by syringe and needle or by the multiple-puncture technique. It confers significant but not absolute immunity; in particular, it protects against the disseminated miliary lesions of tuberculosis and tuberculous meningitis. Disadvantages Various complications have been encountered in the use of BCG. These may be: local chronic ulceration, discharge, abscess formation and keloids; regional adenitis which may or may not suppurate or form sinuses; disseminated a rare complication. The protective efficacy of BCG vaccine has varied considerably in different countries.

Chemoprophylaxis Isoniazid has proved an effective prophylactic agent in preventing infection and progression of infection to severe disease. Treatment with isoniazid for 1 year is recommended for the following groups: close contacts of patients; persons who have converted from tuberculin negative to tuberculin-positive in the previous year; children under 3 years who are tuberculin positive from naturally acquired infection. The tuberculin-negative person may be protected by BCG or isoniazid, the decision as to which method to use would depend on local factors, the acceptability of regular drug therapy, and the availability of effective supervision. SURVEILLANCE OF TUBERCULOSIS For effective control of tuberculosis, there should be a surveillance system to collect, evaluate and analyse all pertinent data, and use such knowledge to plan and evaluate the control programme. The sources of data will include: notification of cases; sputum, chest X-ray; records of BCG immunization routine and mass programmes; overcrowding; data about tuberculosis in cattle; drugs. investigation of contacts, post-mortem reports; laboratory reports on isolation of organisms including the pattern of drug sensitivity; special surveys tuberculin, housing, especially data about utilization of anti tuberculous

Key operations of a national TB programme (NTP) All countries where TB is a public health problem should establish a national TB programme, the key specifics of which are: establishment of a central unit to guarantee the political and operational support for the various levels of the programme; prepare a programme manual; establish a seconding and reporting system; initiate a training programme; establish microscopy services; establish treatment services; secure a regular supply of drugs and diagnostic material; design a plan of supervision; prepare a project development plan. The overall objective is to reduce mortality, morbidity and transmission of TB until it is no longer a threat to public health as speedily as possible.

PNEUMONIAS A variety of organisms may cause acute infection of the lungs. The non-tuberculous pneumonias are usually classified into three groups: pneumococcal; other bacterial; atypical. Pneumococcal pneumonia Pneumococcal infection of the lungs characteristically produces lobar consolidation but bronchopneumonia may occur in susceptible groups. Typically, the untreated case resolves by crisis, but with antibiotic treatment there is usually a rapid response. Metastatic lesions may occur in the meninges, brain, heart valves, pericardium or joints. Pneumonia and bronchopneumonia are two of the major causes of death in the tropics, especially in children. The incubation period is 1 3 days. EPIDEMIOLOGY The disease has a worldwide distribution. Reservoir Humans are the reservoir of infection; this includes sick patients as well as carriers. Transmission Transmission is by air-borne infection and droplets, by direct contact or through contaminated articles. Pneumococcus may persist in the dust for some time.

Host factors All ages are susceptible, but the clinical manifestations are most severe at the extremes of age. Pneumonia may complicate viral infection of the respiratory tract. Exposure, fatigue, alcohol and pregnancy apparently lower resistance to this infection. On recovery, there is some immunity to the homologous type. CONTROL S. pneumoniae generally responds well to penicillin but strains with intermediate resistance occur and strains with high resistance have been isolated The general measures for the prevention of respiratory infections apply avoidance of overcrowding, good ventilation and improved personal hygiene with regard to coughing and spitting. Prompt treatment of cases with antibiotics penicillin, cephalosporins, vancomycin would prevent complications. Chemoprophylaxis with penicillin is indicated in cases of outbreaks in institutions. A polyvalent polysaccharide vaccine is available and has been successfully used in children with sickle cell disease. It is not effective in children under 2years.

OTHER BACTERIAL PNEUMONIAS The other bacteria which can cause pneumonia include: Staphylococcus aureus, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Legionella pneumophila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia psittaci. Although in some cases one particular organism predominates, it is not unusual to encounter mixed infections, especially in persons with chronic lung disorders. The organisms can be isolated on culture of the sputum or occasionally from blood. EPIDEMIOLOGY: These infections have a worldwide distribution and the organisms are commonly found in humans and their environment. Transmission is by droplets, air-borne infection and contact. Host factors: The occurrence of infection is largely determine by host factors such as the presence of viral infection of the respiratory tract (e.g. influenza, measles) or debilitating illness (e.g. diabetes, chronic renal failure). Patients suffering from chronic bronchitis are particularly susceptible. CONTROL: The frequency of these bacterial pneumonias can be diminished by: 1 The prevention or prompt treatment of respiratory disease: viral infection (e.g. measles and influenza vaccination); upper respiratory infection (especially in children and the elderly); chronic lung disease (especially chronic bronchitis). 2 Improvement in housing conditions.

Mycoplasma pneumonia This is an acute febrile illness usually starting with signs of an upper respiratory infection, later spreading to the bronchi and lungs. Radiological examination of the lungs shows hazy patchy infiltration. The incubation period is usually about 12 days, ranging from 7 to 21 days. The infective agent is Mycoplasma pneumoniae (pleuro-pneumonia-like organism). EPIDEMIOLOGY The geographical distribution is worldwide. Humans are the reservoir of infection. It is transmitted from sick patients as well as from persons with subclinical infection. Transmission is by droplet infection and by contact. Only a small proportion of infected persons (1 in 30) show signs of illness. After recovery, the patient is immune for an undefined period. M. pneumoniae spreads easily in institutions such as schools, and military units, the highest incidence is in under 20-year-olds. CONTROL General measures for the control of respiratory diseases apply. Treatment with tetracycline is advocated in cases of pneumonia.

MENINGOCOCCAL INFECTION A variety of clinical manifestations may be produced when human beings are infected with Neisseria meningitidis: the typical clinical picture is of acute pyogenic meningitis with fever, headache, nausea and vomiting, neck stiffness, loss of consciousness and a characteristic petechial rash is often present. The wide spectrum of clinical manifestations ranges from fulminating disease with shock and circulatory collapse to relatively mild meningococcaemia without meningitis presenting as a febrile illness with a rash. The carrier state is common. The incubation period is usually 3 4 days, but may be 2 10 days. Epidemiology There is a worldwide distribution of this infection. Sporadic cases and epidemics occur in most parts of the world, in particular South America and the Middle East, but also in the developed countries of the temperate zone. RESERVOIR Humans are the reservoir of infection. Nasopharyngeal carriage ranges from 1 to 50% and is responsible for infection to persist in a community TRANSMISSION Transmission is by air-borne droplets or from a nasopharyngeal carrier or less commonly from a patient through contact with respiratory droplets or oral secretions. It is a delicate organism, dying rapidly on cooling or drying, and thus indirect transmission is not an important route. Travel and migration, large population movements (e.g. pilgrimages, and overcrowding (e.g. slums), facilitate the circulation of virulent strains inside a country or from country to country.

HOST FACTORS In countries within the meningitis belt the maximum incidence is found in the age group 5 10 years; but in epidemics all age groups may be affected. In institutions such as military barracks, new entrants and recruits usually have higher attack rates than those who have been in long residence. The genetically determined inability to secrete the water-soluble glycoprotein form of the ABO blood group antigens into saliva and other body fluids, is a recognized risk factor for meningococcal disease. The relative risk of non-secretors developing meningococcal infection was found to be 2.9 in a Nigerian study. The reasons why nonsecretors are more susceptible are not known. Control There are four basic approaches to the control of meningococcal infections: the management of sick patients and their contacts; environmental control designed to reduce air-borne infections; immunization; surveillance.

STREPTOCOCCAL INFECTIONS Streptococcus pyogenes, group A haemolytic streptococci can invade various tissues of human skin and subcutaneous tissues, mucous membranes, blood and some deep tissues. The common clinical manifestations of streptococcal infection include streptococcal sore throat, erysipelas, scarlet fever and puerperal fever. Some strains produce an erythrogenic toxin which is responsible for the characteristic erythematous rash of scarlet fever. Rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis result from allergic reactions to streptococcal infections. Epidemiology: have a worldwide occurrence, but the pattern of the distribution of streptococcal disease varies from area to area. Reservoir: Humans are the reservoir of infection; this includes acutely ill and convalescent patients, as well as carriers, especially nasal carriers. Transmission: The sources of infection are the infected discharges of sick patients, droplets, dust and fomites. The infection may be air-borne, through droplets, droplet nuclei or dust. It may be spread by contact or through contaminated milk. HOST FACTORS Although all age groups are liable to infection, children are particularly susceptible. Repeated attacks of tonsillitis and streptococcal sore throat are common but immunity is acquired to the erythrogenic toxin and thus it is rare to have a second attack of scarlet fever with the scarlatinous rash.

Control The general measures for the control of air-borne infections are applicable. In addition, such measures as the pasteurization of milk and aseptic obstetric techniques are of value. Specific chemoprophylaxis with penicillin is indicated for persons who have had rheumatic fever and for those who are liable to recurrent streptococcal skin infections. The penicillin can be given orally in the form of daily doses of penicillin V. RHEUMATIC FEVER Rheumatic fever is a complication of infection with group A haemolytic streptococci. The initial infection may present as a sore throat or may be subclinical; the onset of rheumatic fever is usually 2 3 weeks after the beginning of the throat infection. Apart from fever, the patient may develop pancarditis, arthritis, chorea, subcutaneous nodules and erythema marginatum. Residual damage in the form of chronic valvular heart disease may complicate clinical or subclinical cases of rheumatic fever; the complication is more liable to occur after repeated attacks. Epidemiology The disease has a worldwide occurrence. Although there is a falling incidence in the developed countries of the temperate zone, it is becoming a more prominent problem in the overcrowded urban areas of some tropical and subtropical countries, for example in South East Asia and the Middle East. Rheumatic fever represents an allergic response in a small proportion of persons who have streptococcal sore throat. The factors that determine this sensitivity reaction are not known.

Control The control of rheumatic fever involves the control of streptococcal infections in the community generally and the prevention of recurrences by chemoprophylaxis after recovery from an attack of rheumatic fever. PERTUSSIS (WHOOPING COUGH) Infection with Bordetella pertussis leads to inflammation of the lower respiratory tract from the trachea to the bronchioles. Clinically, the infection is characterized by paroxysmal attacks of violent cough; a rapid succession of coughs typically ends with a characteristic loud, high-pitched inspiratory crowing sound the so-called whoop . Epidemiology: The disease has a worldwide distribution but there is falling morbidity and mortality following immunization programmes. Humans are the reservoir of infection. Transmission of infection may be air-borne or by contact with freshly soiled articles. Children under 1 year old are highly susceptible and most deaths occur in young infants. Control INDIVIDUAL: Sick children should be kept away from susceptible children during the catarrhal phase of the whooping cough; isolation need not be continued beyond 3 weeks because the patient is no longer highly infectious even though the whoop persists. VACCINATION: Routine active immunization with killed vaccine is highly recommended for all infants. The pertussis vaccine is usually incorporated as a constituent of the triple antigen DPT (diphtheria pertussis tetanus), which is used for the immunization of children starting from 2 to 3 months. It provides immunity for about 12 years.

DIPHTHERIA This disease is caused by infection with Corynebacterium diphtheriae (Klebs Loeffler bacillus). There may be acute infection of the mucous membranes of the tonsils, pharynx, larynx or nose; skin infections may also occur and are of particular importance in tropical countries. Much faucial swelling may be produced by the local inflammatory reaction and the membranous exudate in the larynx may cause respiratory obstruction. The exotoxin which is produced by the organism may cause nerve palsies or myocarditis. The incubation period is 2 5 days. Epidemiology Although there is a worldwide occurrence of the disease, this once common epidemic disease of childhood is now well controlled in most developed countries by routine immunization of infants. There is evidence to suggest that in some parts of the tropics a high proportion of the community acquires immunity through subclinical infections, mainly in the form of cutaneous lesions. RESERVOIR Humans are the reservoir of infection; this includes clinical cases and also carriers. TRANSMISSION The infective agents may be discharged from the nose and throat or from skin lesions. The transmission of the infection may be by: air-borne infection; direct contact; ingestion of contaminated raw milk. indirect contact through fomites;

HOST FACTORS All persons are liable to infection but susceptibility to infection may be modified by previous natural exposure to infection and immunization. The newborn baby may be protected for up to 6 months through the transplacental transmission of antibodies from an immune mother. The cutaneous lesions which are often not recognized produce immunization of the host with low morbidity. Susceptibility to infection may be tested by means of the Schick test: a test dose of 0.2 ml of diluted toxin is injected intradermally into one forearm, with a similar injection of toxin, destroyed by heat, into the other forearm to serve as a control. Apositive Schick test, consists of an area of redness 1 2 cm diameter at the site of the test dose, reaching its maximum size in 3 4 days, later fading into a brown stain. This positive reaction is confirmed by the absence of reaction at the site of the control injection. Redness at both sides is recorded as a pseudoreaction, and probably represents nonspecific sensitivity to some of the protein substances in the injection. A negative Schick test is recorded when there is no redness at either injection site. Both the pseudoreaction and the negative Schick test are accepted as indicating resistance to diphtheria infection. Control Antitoxin should be given promptly on making the clinical diagnosis and without awaiting laboratory confirmation. Treatment with penicillin or other antibiotics may be given in addition to, but not instead of, serum. The patient should be isolated until throat cultures cease to yield toxigenic strains. However, a patient is expected to be non- contagious within 48 hours of antibiotic administration. Isolation should be maintained until elimination of the organisms is demonstrated by two negative cultures obtained at least 24 hours apart after completion of antimicrobial therapy.

CONTACTS Non-immune young children who have been in direct contact with the patient should be protected by passive immunization with antitoxic serum and at the same time, active immunization with toxoid is commenced. Susceptible (Schick-positive) adult contacts should be protected with active immunization and a booster dose can be given to immune (Schick-negative) persons. It is now recommended that all close contacts should receive antibiotic prophylaxis to be maintained for a week. THE COMMUNITY The search for carriers and their treatment with antibiotics may be indicated in the special circumstances of an outbreak in a closed community such as a boarding school, but the major approach to the control of this infection is routine active immunization of the susceptible population. ACTIVE IMMUNIZATION Active immunization with diphtheria toxoid has proved a reliable measure for the control of this infection. It is usually administered in combination with pertussis vaccine and tetanus toxoid (DPT or triple antigen) from the age of 2 to 3 months. A booster dose of diphtheria toxoid is recommended at school entry and this may be given in combination with typhoid vaccine. The following are the internationally accepted interpretations of the levels of circulating diphtheria toxin antibodies expressed in IU/ml: 0.01: Susceptible 0.01 0.09: Basic protection 0.1: Full protection 1.0: Long-term protection

FUNGAL INFECTIONS HISTOPLASMOSIS The classical form of histoplasmosis due to Histoplasma capsulatum presents a variety of clinical manifestations. Infection is mostly asymptomatic, being detected only on immunological tests. On first exposure there may be an acute benign respiratory illness, which tends to be self-limiting, healing with or without calcification. Progressive disseminated lesions may occur with widespread involvement of the reticulo-endothelial system; without treatment this form may have a fatal outcome. The incubation period is from 1 to 21 weeks. Little is known about its reservoir, mode of transmission or other epidemiological factors. Epidemiology The infection is endemic in certain parts of North, Central and South America, Africa and parts of the Far East. RESERVOIR The reservoir is in soil, especially chicken coops, bat caves and areas polluted with pigeon droppings. TRANSMISSION The infection is acquired by inhalation of the spores. Person to person transmission is rare. HOST FACTORS It is not clear why in some patients the infection progresses to severe disease. Control The main measure is to avoid exposure to contaminated soil and caves. Infected patients with significant disease can be treated with Amphotericin B.