Understanding Quantifiers in Symbolizing Statements

Exploring different ways of symbolizing statements using predicates and subjects, delving into universal and existential quantifiers to express relationships within categories such as animals, cats, and dogs.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Adapted from Patrick J. Hurley, A Concise Introduction to Logic (Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth, 2008).

Before I go on to explain quantifiers, first let me address different ways of symbolizing statements. Previously, we used one letter to symbolize one statement. But there is another way to symbolize certain kinds of statements that are relevant to quantifiers. We can also symbolize statements by symbolizing the predicate and subject separately. E.g. Luna is a cat. = Cl (C= is a cat; l=Luna)

The relationship has a parallel in functional or quantificational statements. Luna is only an instance of a cat. There can be many cats. Cats is the universal category governing whether a constant or variable counts as one of the things the term refers to, and Luna is the particular instantiation or constant.

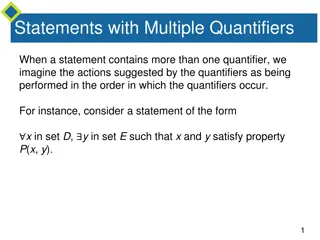

Instead of Luna is a cat, what if I wanted to say something about all cats or some cats as a category? This is when we use quantification. Let s say I want to say All cats are animals . The symbol Ac does not cut it because the lower case c represents only an individual. When I want to say something about all cats (or no cats), I need to use the symbol ( x).

x symbolizes the quantifier in universal statements: ( x)(Cx Ax) All cats are animals. = (Translation: For every x, if x is a cat, then x is an animal.) ( x)(Cx Dx) No cats are dogs. (Translation: For every x, if x is a cat, then x is not a dog.) =

The previous slide contains statements about x such that for EVERY x, if x is a cat, then it is an animal. It is not just about one individual, but about the whole category of cats, dogs and animals. See the next slide for Existential Statements.

x symbolizes the quantifier in existential statements. Some apples are red. = ( x)(Ax Rx) (Translation: There exists an x such that x is an apple and x is red.) Some apples are not red. = ( x)(Ax Rx) (Translation: There exists an x such that x is an apple and x is not red.)

Statement Symbolic translation ( x) (Mx Hx) ( x) (Px Lx) ( x)Ax ~( x)Ux ( x)Cx ( x) (Sx Mx) ( x) (Ex ~Px) There are happy marriages. Every pediatrician loses sleep. Animals exist. Unicorns do not exist. Anything is conceivable Sea lions are mammals. Egomaniacs are not pleasant companions. A few egomaniacs did not arrive on time. Only close friends were invited to the wedding. ( x) (Ex ~Ax) ( x) (Ix Cx)

Translate the following statements into symbolic form. Avoid negation signs preceding quantifiers. The predicate letters are given in parentheses. 1. Elaine is a chemist. (C) 2. Nancy is not a sales clerk. (S) 3. Intel designs a faster chip only if Micron does. (D) 4. Some grapes are sour. (G, S) 5. Every penguin loves ice. (P, L) 6. There is trouble in River City. (T, R) 7. Tigers exist. (T)

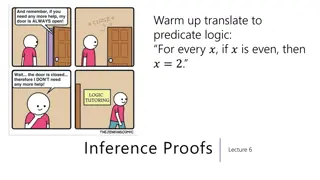

There are a number of logical inferences that we use in every day language, logic, and math. Logic has names for them. Once you identify them, it makes those inferences explicit. Your textbook mentions six such inferences, and I will give them labels: modus ponens, modus tollens, disjunctive syllogism, conjunction, simplification, and addition.

We have run across this inference before. The rule of modus ponens is that if you have a conditional and assert the antecedent, you may infer the consequent. E.g. If it rains, then the ground gets wet. It is raining. Therefore, the ground is wet.

This is an inference that also works off a conditional, but it asserts something about the consequent. If you have a conditional, and assert the negation of the consequent, you can infer the negation of the antecedent. E.g. If it rains, then the ground gets wet. The ground did not get wet. Therefore, it did not rain.

In the disjunctive syllogism, if you have a disjunction and negate one side of the disjunctive, you may infer the non-negated side of the disjunctive. E.g. Either the chalk is black or the chalk is white. The chalk is not black. Therefore, the chalk is white.

This inference can be symbolized this way: B V W ~B W

In this type of inference, if you have two established statements, then you may also conjoin them to make a single statement. E.g. Chalk is white. Snow is white. Chalk and snow are white.

In this inference, if you have two statements that are conjoined into a complex statement, you may infer one part of the complex statement. E.g. Chalk and snow are white. Chalk is white.

In this inference, if you have a statement, you may properly add a disjunction without falsifying the original statement. E.g. Chalk is white. Chalk is white or Rudolf ate my homework.

The previous inference can be symbolized this way: C C V R

Fill in the missing premise and give the inference that justifies the conclusion. (1) 1. B v K 2. ______ 3. K ____ (2) 1. N S 2. ______ 3. S ____ (3) 1. K T 2. ______ 3. ~K ____

(1) 1. ~A 2. A v E 3. ______ ____ 4. ~A E ____ (2) 1. T 2. T G 3. (T v U) H 4. ___________ ____ 5. H ____ (3) 1. M 2. (M E) D 3. E 4. __________ ____ 5. D ____