Understanding Hamartia in Greek Tragedies: Analysis of Human Error

This insightful analysis delves into the concept of hamartia in Greek tragedies, exploring the idea of human error and its impact on tragic heroes. From Aristotle's definition to the intertwining of hubris and moira, the discussion uncovers the complexities of fate, choice, and suffering in these timeless literary works.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

HAMARTIA Reflections upon the nature of things or an analysis of the human condition was not the aim of dianoia (ferment of thoughts that leads to the point of choice). Thinking was for choosing, doing this or that. Action was the culmination of ethos. But in spite of his best efforts and courageous choice, Man fails. To explain the logic of failure, Aristotle has used the term hamartia which means hitting off the mark. It is an error of judgement made inadvertently. A large number of Greek tragedies have little room even for hamartia. Andromache, Supplices, Antigone, Daughters of Troy, Electra, Eumenides, are all plays in which misfortune sets in motion even before the protagonist realises its presence.

HAMARTIA (I) In the majority of the tragedies the events are predetermined, a God has decided to destroy someone as in Hippolytus, or family duty holds the individual in absolute bondage as in Oresteia, Electra or Antigone. Hamartia, then, is a brief appearance in the action sequence of the hero, as an action which at the time of doing does not seem that consequential such as Oedipus' killing the old man in ignorance, or Hippolytus' rebuking the advances of his mother.

HAMARTIA(II) The value of hamartia was highly raIsed in Christian as well as in modem moralistic tragedy where the downfall of the hero is caused by a cardinal sin or a serious lapse. In Christian or moralistic tragedy, pity for the protagonist and horror at excessive suffering, are both benumbed. In the Greek world, there was no free- will. Even by making the right choice the hero could not avert a calamity or suffering, because his suffering was not always caused by his weakness. It was not the ambition of a Macbeth, the jealousy of an Othello or the arrogance of a Lear, nor was it the inner sin that destroyed a man, but instead it was the dilemma imposed upon him by forces far beyond his control that caused his destruction.

HAMARTIA(III) His ethos or character was revealed in his choosing an admirable way to death. Here suffering comes not from within but from without. Instead of the Semitic, this was the Indo-Greek perception of Man's destiny. Here, two terms, moira and hubris, often used in this context, further indicate the helplessness of mankind. Moira, literally meaning portion or the family share, metaphorically came to indicate the share of misfortune allotted by the gods. Hubris meant the daring, sometimes transgression, that the hero made or committed in his desperate effort to escape impending misfortune, Hubris and hamartia were rather intertwined in the course of action.

HAMARTIA(IV) It should nevertheless be remembered that hubris and moira are not terms used as categories by Aristotle. They were concepts used by the Greeks to define human behaviour.

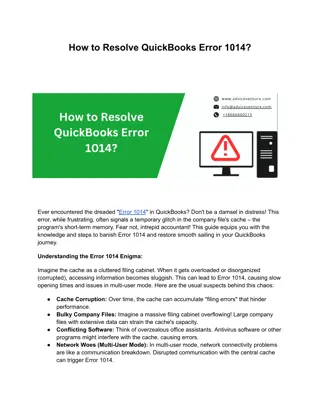

Aristotelian Tragedy in Oedipus the King ARISTOTLE (384-322 BC) Philosopher and academic, wrote prolifically He was writing at least three generations after Sophocles plays were seen. Certainly he had access to the text, but Sophocles did NOT follow Aristotle s theory of tragedy.

Aristotles Guide to a Terrific Tragedy According to Aristotle a good tragedy, like a good cake, must have the following ingredients to be successful: 1. The tragic ending is inevitable 2. The tragic character has a tragic flaw (hamartia) which leads to his/her downfall 3. The tragic character is of high status, so that his/her fall has great impact SIMPLE VERSION

Aristotelian Tragedy in Oedipus the King Greek Term English Explanation Oedipus the King examples Oedipus does not know that the person he killed at the crossroads was the King of Thebes, Laius Oedipus does not know that Laius was his father Oedipus does not know that Jocasta is his mother Oedipus does not know that Polybus and Merop are not his natural parents Oedipus kills Laius Oedipus sleeps with Jocasta and produces 4 children, Antigone, Ismene, Polynices and Eteocles hamartia ignorance pathos tragic acts The messenger tells Oedipus that he is to be King of Corinth good news; but he ends up revealing that Polybus and Merop were not the parents of Oedipus The shepherd is summoned to give evidence about the death of Laius; he ends up revealing that Oedipus was the baby whom he rescued from and gave to the messenger Oedipus finally makes the connection that the man he killed at the crossroads was his own father Laius, and that the woman he has married and slept with (Jocasta) is his own mother. peripeteia a reversal of action/intent anagnorisis recognition (of ignorance) Oedipus acknowledges to the chorus and audience that he is a hated and revolting creature. He blinds himself vigorously and violently it s not just the blinding, but how it s done He is resigned to his fate and urges Creon to banish him, thus purifying the city of Thebes. catharsis purification