Understanding Graduate-Level Writing in Academic Communication

Explore the nuances of academic writing at the graduate level in the School of Communication with Francesca Gacho, a Graduate Writing Coach. Learn about the features, characteristics, and strategies necessary for various genres of writing in this context. Discover the expectations and conventions of academic writing, including its distinct features and the additional requirements of graduate-level writing, such as original perspectives and ethical use of scholarly sources.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

GRADUATE-LEVEL WRITING IN THE SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION By Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach Annenberg School of Communication fgacho@usc.edu | annnenberg.usc.edu/graduate-writing

Today we will discuss Definition of academic writing Features of academic graduate-level writing Types of writing you might be expected to write in the School of Communication Basic definitions, characteristics, and strategies for approaching different genres of writing Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

What is Academic Writing Academic writing refers to a style of writing typically used and seen in academic settings school or university, workplace, and other similar settings. Essays, proposals, memoranda, reports, analyses, theses, dissertations, journal articles, book-length manuscripts, etc. Compared to journalistic writing which is another genre of prose academic writing often requires More explicit signaling to show coherence or logical flow of ideas to the reader Longer texts (word count and/or page requirement) Specific rhetorical moves Higher level of diction; more formal Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Features of Academic Writing Answers a question Shows intellectual rigor Analyzes of information Logically & coherently structured Appropriately and correctly cited Formatted correctly according to discipline style Proofread for spelling, grammatical, and mechanical errors Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

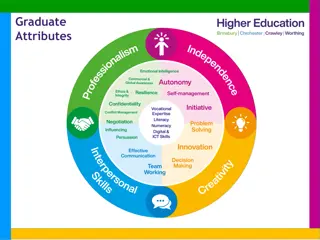

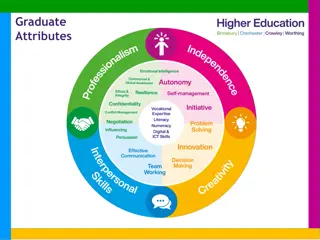

Features of Graduate-Level Writing All of those previous features I just listed plus the following: Add to existing knowledge in your field(s) Offer unique perspective(s) on concepts Adept and ethical use of scholarly sources Full grasp of the conventions of your field(s) Appeals to audience of specialized knowledge or skill, but clear and engaging Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Writing at the Graduate Level Think of graduate writing as graduate becoming Developing professional identity, voice, and persona. Grasping content knowledge and rhetorical awareness and flexibility. Graduate-level writing is also a genre of writing Its conventions can be learned, transformed, and shared through learning how your field communicates with its members and how members communicate their knowledge with different audiences. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Your Rhetorical Situation Ask the following questions when evaluating your rhetorical situation Audience: who will be reading? Context: what does my audience already know about this? Purpose: why am I (the author) writing? Stance: what my position or POV is? Genre: what kind of text is this? Tone: how should I convey my idea? Medium: how will people read this? (online, in print, as a tweet, etc.) Design: how do I use visual elements to convey my idea? Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Four Types of Writing in the School of Communication Humanities Writing Usually concept- or argument-driven papers Analytical or argumentative research papers, reaction/response papers Social Science Writing Typically empirical papers that follow APA format for social science papers Empirical research papers, literature reviews, reports, case studies, methodological articles Business Writing User-oriented documents focused on communicating to (potential) investors, other stakeholders Business or marketing proposals/pitches, online website/portfolio, SWOT analyses Hybrid Genres Documents that combine any of these genres to fulfill assignment requirements Case studies, SWOT analyses, Interview & Analysis papers Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Humanities-Style Writing In your courses, you might be expected to write a seminar or course paper. Seminar papers are culminating writing projects that typically demonstrate the writer s position about a topic or a set of related topics (or texts or concepts) related to your course. They present an original argument that demonstrates the writer s understanding of course concepts, their implications, and/or applications. They are supported by secondary sources or other forms of credible and scholarly evidence. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Sample Writing Assignment Prompt Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

How to Approach Humanities- Style Papers Always begin with your rhetorical situation and assignment prompt. Select your topic and text [what you will be reading or interpreting ]. 1. Have a focal point that your paper will ask: What s confusing/strange/unique/prominent/paradoxical about the way the text I m interested in deals with this topic? 2. Use your focal point to identify a question (or a set of questions). 3. Join the theoretical conversation. What conversation(s) am I entering into? What frameworks currently exist to explain this focal point I m interested in? How will using these theories help me answer my question in a new and interesting way? 4. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

How to Approach Humanities- Style Papers, continued Engage in critical conversations. Have the critics who ve written about this text noticed this same focal point? Have they asked this question? If not, why? If so, how have they answered it? What remains unsaid or unsatisfactory about what has been said? Why is my contribution new? 5. Provide your argument. This answer should constitute a new and original claim about how the text operates, the ideas it expresses, or its relation to its context. 6. Tell your reader how this changes our understanding of the theory and text.* 7. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Social Science Writing Scientific writing is a genre of academic writing that is most commonly used in the Sciences (including Education). Social Science writing typically follows the APA formatting and citation style for writing documents. Papers that follow a social science structure may include research papers where you have to conduct an experiment, survey, focus group or interview, or simulations to investigate a research question or problem. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Types of Social Science Writing Empirical Studies: original research that tests a hypothesis (Intro, Method, Results, Discussion) Literature Reviews: synthesize research or provide a meta-analysis to statistically combine results from various studies to identify gaps and suggest next steps Theoretical Articles: similar to a lit review, except only presents information related to analyzing and comparing existing theories Methodological Articles: compares effectiveness of different research methods and/or presents a new approach, gives enough detail for researchers to implement ideal methods Case Studies: illustrate a problem using a particular individual/community/organization as an example Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Shape of a Scientific Paper Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

How to Approach Scientific Papers Always begin with your rhetorical situation and assignment prompt. Select a topicand do exploratory research to figure out what has been understudied, overlooked, or underexplained in that research area. Narrow to a specific research question. Use literature based on the research question to help you form hypotheses, methodological approach(es), and give you an idea of how your own research differs from what has come before. When using empirical evidence, be meticulous about data gathering and interpretation. When using secondary sources, make sure your sources are credible, scholarly, and accurate. Tell your reader why your research matters. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Business Writing Business writing is a genre of writing that is often used in business or corporate communications. You might be asked to create documents intended to communicate with various stakeholders such as executives, employees, customers, investors, and other stakeholders. Examples include business or marketing pitch or proposal, create a website using language that fits online and web communication, Press Releases, executive summaries Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Characteristics of Business Writing Action-oriented Reader must know what and why he or she is reading the document. Tells the reader what to do (if any) Rhetorical Persuasive? Informative? Directive? User-centric Think about what the user or reader will find helpful or informative. Anticipate possible questions and/or objections. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Sample Assignment Prompts Synthesizing; evaluation. Practitioner piece; intended for the client Writing style = reflects that of the client s organization Analysis; make recommendations for improvement 10-15 pages List of items to include Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Shape of Business Documents The Inverted Pyramid style typically used in journalism The widest part of the pyramid answers 5W s and How; most substantial and important part The narrower part of the pyramid includes important details relevant to point (quotes, statistics, contexts) The narrowest part gives the reader background information or other general information (nice to know, but not essential) Most important detail or information General, less important information Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

How to Approach Business Writing Always begin with your rhetorical situation and assignment prompt. Narrow your main idea and what message you want to relay. 1. Prioritize clear, transparent, and compelling language but do not exaggerate or mislead. 2. Design matters in business writing! Consider using bullet points, graphs, tables, images, to drive your point home. 3. Keep in mind what your audience knows (or doesn t know) and provide information accordingly. 4. Organize and design your document so that the reader can easily navigate it (whether by using headers, numbered lists, etc.). 5. Use compelling and accurate data/evidence. 6. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Hybrid Writing Genres Sometimes, you might be asked to write papers that are dual- purposes or papers that combine writing genres. For example, you might be asked to write a Business Proposal that uses academic sources and course content. Should this be in academic writing style or business writing style? The rules here are not so clear, but you should always go back to the assignment prompt and make sure you re meeting the requirements. When in doubt, check in with your professor. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

How to Approach Hybrid Genre Papers Your rhetorical situation is particularly important here. Depending on what you re writing, the design, context, and audience are likely to differ greatly from a social science or humanities-style paper. Hybrid Genres attempt to address usually more than 1 primary audience, typically the professor (who has to grade your grasp of course concepts and their applications) and a stakeholder (perhaps a business client or a practitioner, who has to be convinced of your proposal or recommendations). Pay close attention to your assignment guide (if there is one) and what s required. Look up process words to get a sense of what you re supposed to include and accomplish with the text. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Sample Writing Assignment Prompts, part 2 Slides for readings; 5 articles each Lead discussion and supplement presentation with other materials

Sample Assignment Prompt part 3 Oral presentation on a literature review Different topic from Part 1 Focus on principal findings of the literature review 15 references minimum Conclude with suggested RQs or hypotheses that would advance conversation in the research area.

MORE SAMPLE PROMPTS

Some advice on style Above all, be clear. Keep your rhetorical situation in mind. Present your work fully, support your points by providing credible examples, and never add anything that is irrelevant. Do what you say you are going to do (follow your thesis). Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

Some key things to remember Writing is situational.These generic conventions I ve outlined here today suggest what the expectations are, but remember that every writing task is a response to a particular time, need, or problem. Use these to guide your process, but the final form, structure, and content is up to you and in negotiation with your task. Critical writing is the beginning, not the end. Our shared goal is these writing tasks you re doing in class is to develop your knowledge and expertise. There is no one right way to write, but there are common styles and strategies that you will learn along the way. Writing well takes time and practice. Writing well is a cumulative practice and process. As you go through your program and write more, you will begin to learn how to write in your field. Take note and practice often. Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

References APA 7th Edition Style Blog. https://apastyle.apa.org/blog/ Garner, B. (2012). HBR Guide to Better Business Writing. Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press. Gacho, F. (2017). USC Annenberg Graduate Writing Coach. Resources. http://cmgtwriting.uscannenberg.org/resources-2/ Hayot, E. (2014). The Elements of Academic Style: Writing for the Humanities. New York: Columbia University Press. Labaree, R. (n.d.). How to organize your social sciences research paper. USC Library Research Guide. https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide Singh, A. A. & Lukkarila, L. (2017). Successful Academic Writing: A Complete Guide for Social and Behavioral Scientists. New York: Guilford Press. Swales, J. & Feak, C. (2012). Academic Writing for Graduate Students. 3rd ed. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Turbek et. al. (2016). Scientific writing made easy: A step-by-step guide to undergraduate writing in the biological sciences. The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America(97)4, 417-426. USC Library Tutorials. https://libraries.usc.edu/research/reference-tutorials Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach, fgacho@usc.edu

GRADUATE-LEVEL WRITING IN THE SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION By Francesca Gacho, Graduate Writing Coach Annenberg School of Communication fgacho@usc.edu | annenberg.usc.edu/graduate-writing