The Impact of Stadium Subsidies on Urban Economic Development

Stadium subsidies for commercial sports, particularly in the US, have raised concerns about their impact on urban economic development. Many stadiums are heavily subsidized, shifting costs onto the public to fund luxury boxes rather than more seats. This allocation of resources raises questions about who truly benefits from these subsidies - owners, players, or fans. The division between public and private financing, as well as the construction of new sporting venues, further complicates the economic implications of such subsidies.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

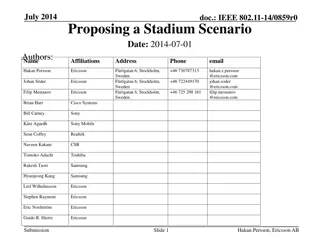

Getting Into the Game: Sport as aStimulus for Urban Economic Development By: Robert A. Baade A.B. Dick Professor of Economics, Lake Forest College and President Emeritus, International Association of Sports Economists (IASE) for the Public Affairs Forum Sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Birmingham, Alabama on July 17, 2014

Purpose: Is commercial sport a catalyst for urban economic development?

COMMERCIAL SPORT IS HEAVILY SUBSIDIZED IN THE US The real demand is for luxury boxes, not more seats. So the average working person is asked to put a tax on their home or pay sales or some other consumer tax to build luxury boxes in which they cannot afford to sit. Frequently, the new stadium is smaller. The working person is asked to be satisfied with sense of pride they get from this arrangement, which will last until another team bids more for their players, or until another city bids for the team. Houston Mayor, Bob Lanier Testimony Before the Senate Judiciary Committee November 29, 1995

Stadiums Built/Proposed Number of stadiums 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0

Cost of Stadiums Millions of 2007 dollars 10000 9000 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0

Percentage Financed by Public Percent 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1900-391940-591960-691970-791980-891990-952001-052006-10

Who benefits from stadium subsidies?

Proportion of Facilities Financed by the Public and Private Sectors by League and the Impact of New Facilities on Revenues and Incomes by League Leagues building new venues ______________________________________________________________________________________ Average total cost ($m)* Contribution (%) Public Private Incremental Incremental revenues ($m) incomes ($m) Major League Baseball National Basketball Association 169 National Football League National Hockey League (NHL) 148 269 77 23 31 69 74 26 42 58 11 89 19.1 17.4 18.8 15.7 20.3 12.7 5.4 12.0 7.7 11.6 257 191 Shared NBA and NHL facilities

MLB Payrolls ($m) Before and After New Stadiums Built Between 1991 and 2001 ________________________________________________________________________________ Team (year new Team payroll Total payroll stadium opened: t) for year t t - 2 (% of payroll t)(% of payroll t) ________________________________________________________________________________ Arizona (1998) 29.16 n.a. Total payroll t - 1 Total payroll t + 1 (% of payroll t)(% of payroll t) Total payroll) t + 2 n.a. (241) 47.93 (95) 14.63 (70) 9.49 (56) 15.72 (55) 22.98 (74) 34.96 (57) 55.29 (106) 35.78 (79) 29.56 (51) 46.06 (86) 52.03 (117) 35.64 (110) (73) 70.37 (267) 59.54 (118) 26.92 (128) 28.41 (169) 35.19 (124) 34.92 (112) 49.36 (80) 60.39 (115) 50.29 (112) 42.32 (73) 63.28 (118) 59.22 (133) 32.37 (100) (125) 77.88 Atlanta (1997) 50.49 45.2 (90) 10.04 (48) 7.60 (45) 8.24 (29) 8.83 (28) 22.63 (37) 40.63 (78) 42.93 (95) 24.22 (42) 40.32 (75) 39.67 (89) 29.74 (92) (57) 75.07 (149) 37.67 (179) 34.60 (206) 45.32 (159) 42.87 (138) 55.05 (89) 63.45 (121) 40.63 (90) 54.81 (95) 78.30 (146) 74.72 (168) 35.86 (111) (147) Baltimore (1992) 20.99 Chicago White Sox (1991) 16.83 Cleveland (1994) 28.49 Colorado (1995) 31.15 Detroit (2000) 61.74 Houston (2000) 52.36 Milwaukee (2001) 45.10 Pittsburgh (2001) 57.76 San Francisco (2000) 53.54 Seattle (1999) 44.37 Texas (1994) 32.42 Average _________________________________________________________________________________

Ticket Prices Before and After New Stadiums Built Between 1991 and 2001 ______________________________________________________________________________ Team (year new Ticket pricesTicket prices Ticket prices Ticket prices Ticket prices Stadium opened: t) for year t t - 2 (% of prices t) (% of prices t) (% of prices t) (% of prices t) ______________________________________________________________________________ Atlanta (1997) 15.54 12.00 (77) Baltimore (1992) 9.65 n.a. t - 1 t + 1 t + 2 13.06 (84) 10.30 (107) n.a. 17.78 (114) 11.12 (115) 11.70 (114) 12.06 (100) 10.61 (100) 23.90 (96) 20.03 (100) 17.63 (97) 19.51 (91) 23.38 (110) 23.38 (100) 12.07 (100) (102) 19.21 (124) 11.12 (115) 11.70 (114) 14.52 (120) 11.38 (107) 20.44 (82) 18.87 (94) n.a. 10.28 n.a. Chicago White Sox (1991) Cleveland (1994) 12.06 7.70 (64) 7.91 (75) 10.40 (42) 11.88 (59) 11.02 (60) 10.71 (50) 11.47 (54) 14.94 (64) 8.93 (74) (60) 8.70 (72) 7.90 (74) 12.23 (49) 13.30 (66) 11.72 (65) 11.80 (55) 12.12 (57) 19.01 (81) 8.93 (74) (66) Colorado (1995) 10.61 Detroit (2000) 24.83 Houston (2000) 20.01 Milwaukee (2001) 18.12 Pittsburgh (2001) 21.48 n.a. 20.84 (98) 24.60 (105) 11.96 (99) (104) San Francisco (2000) 21.24 Seattle (1999) 23.42 Texas (1994) 12.07 Average _______________________________________________________________________________ 16.71

Do cities and regions benefit from sports subsidies?

Ex ante analysis Minnesota lawmakers heard last month that a $954 million Vikings stadium would employ 8,000 construction workers another 5,400 people supported by construction-related spending and 3,400 in the new facility. Team vice president Lester Bagley called it a "significant jobs and economic stimulus package." (Associated Press, March 5, 2009)

Ex ante or prospective analysis is difficult. Precise estimates require extensive knowledge on the way different sectors of the economy interact. Despite the best efforts of economists, a model that explains urban economic growth within acceptable margins of error eludes the profession. That reality makes all ex ante analysis somewhat suspect.

Why ex postanalysis is necessary to evaluate the efficacy of commercial sports subsidies?

Economic Impact Estimates Provided by Boosters for Selected Teams, Facilities, and Events Year of Study 1992 1995 1996 Team, Facility, or Event Area Measured Impact ($millions) NBA All Star Game Summer Olympic Games Cincinnati Reds (MLB) Old Stadium* Metro Orlando Metro Atlanta Metro Cincinnati 35a 5,142b 158c 1996 1998 1999 Cincinnati Reds New Stadium* Arizona Diamondbacks Super Bowl Metro Cincinnati Metro Phoenix South Florida (Miami, Dade and Broward Counties) Metro Boston 192c 319c 396d 1999 Boston Red Sox (MLB) Current Stadium* Boston Red Sox New Stadium* San Antonio Spurs (NBA) 120c 1999 1999 Metro Boston Metro San Antonio Metro Dallas MetroHouston Countries of Japan and South Korea 186c 71c 1999 2000 2001 Summer Olympics Dallas Houston Rockets (NBA) World Cup Soccer 4,000e 187c 24,800 (Japan) 8,900 (S. Korea)f

Quality of life and compensating differentials arguments Economists know the price of everything and the value of nothing. ---Oscar Wilde

What do contingent valuation studies tell us?

Compensating differentials Entertainment village in Ottawa, Canada: Project would include offices, restaurants, bars, apartments, hotels for area near Senators arena

Conclusions and policy implications The sum total of the evidence does not suggest that sport subsidies standing alone produce social value in excess of their social costs. As part of a larger redevelopment plan, expenditures on teams, facilities, and sports mega-events may induce an increase in economic activity in the urban core, but that may come at the expense of other parts of the metropolitan or regional economies.

Finally, since the preponderance of evidence does not support the notion that subsidies for sport alone can serve as catalysts for economic development, subsidy debates should focus on the public benefits as they relate to the enhanced quality of life imparted by teams, facilities, and sports mega-events. Future research should focus on techniques for estimating the hedonic component of subsidies for sport, and both the contingent valuation method and estimates for compensating differentials show promise in that regard. Moon Landrieu may have been right: It is the very building of it that is important, not how much it is used or its economics.