The Development Pattern and Rationale Behind Economic Nationalism in India

Three core elements - economic planning, autarchy, and building socialism - define India's development pattern focused on self-sufficiency and state ownership of industries. The rationale behind this approach is debated between economic theory influences and Marxist perspectives, reflecting a commitment to economic nationalism embodied in the Mahalanobis model.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

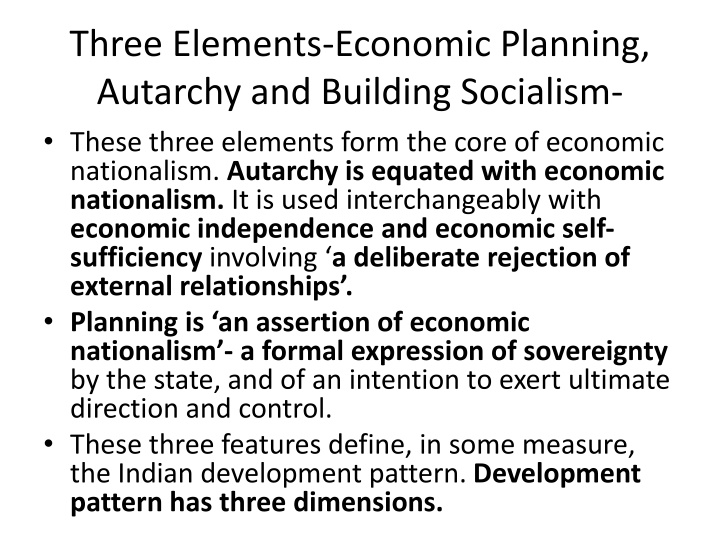

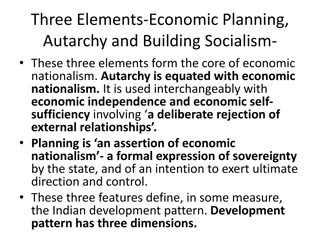

Three Elements-Economic Planning, Autarchy and Building Socialism- These three elements form the core of economic nationalism. Autarchy is equated with economic nationalism. It is used interchangeably with economic independence and economic self- sufficiency involving a deliberate rejection of external relationships . Planning is an assertion of economic nationalism - a formal expression of sovereignty by the state, and of an intention to exert ultimate direction and control. These three features define, in some measure, the Indian development pattern. Development pattern has three dimensions.

Development Pattern in India 1. i. ii. Three dimensions of development pattern: The kind of industries accorded prominence; The orientation of these industries to the world economy (whether they are oriented inward or outward); and The economic agents chosen for development. In the Indian development pattern i) the emphasis was placed on capital goods, heavy, basic, investment goods industries ( metal- making and heavy engineering industries) in Indian planning; ii) These industries were inward oriented and were expected to make the Indian economy self-sufficient as well as self-reliant for future sustained growth; and iii) They were to be both owned and managed by the state. This pattern was executed with full force only between 1956 and 1965 but lasted in its broader dimensions until 1991. iii.

The Rationale Behind This Development Pattern i. There are two major interpretations in the literature: One interpretation focuses on economic theory or economic ideas of the time as being influential in the policy change (theoretical justification or validation). A key proponent of this view- Sukhamoy Chakravarty, a distinguished internationally renowned economist and economic planner. Bimal Jalan, another economist and economic planner was another proponent of this view. The immediate intellectual basis for the economic strategy that led to the Indian development pattern had been the plan-frame for the Second Five Year Plan (1956-61) and the underlying economic model (Mahalanobis model). Both were put forward by the eminent economic planner P.C. Mahalanobis.

The Second Interpretation by Marxist Activists and Scholars This view debunks any claims to building socialism and forthrightly proclaims the intent in the economic strategy as building, instead, capitalism on behalf of the bourgeoisie or capitalist class. E.M.S. Namboodiripad, the eminent communist leader declares that Nehru represented, and acted as the spokesman of a particular class-the Indian bourgeoisie and defended their class interests. Marxist scholar Prof Prabhat Patnaik states that the class-configuration which prevailed, upon which industrial capitalism was to develop, dictated in broad terms a certain course of action, and the Mahalanobis model fitted in with this .

Mahalanobis Model: A Commitment to Economic Nationalism The first of the two interpretations about the affinity between the Mahalanobis model and the then prevailing economic theory serves merely to detract from a deeper analysis into the origins of the model. In a more profound sense, the Mahalanobis model was, indeed, founded on the historical commitment of the freedom movement to economic nationalism. With due regards to the theoretical merits of the Mahalanobis model it needs to be stated that the model simply provided a theoretical scaffolding for an economic architecture already determined on political grounds, without the benefit of or any reference to economic theory. Thus a more appropriate explanation for the strategy is a theory of power instead of the power of theory .

A Mechanical Application of the Marxist Theory The Marxist critique errs in making a mechanical application of the Marxist theory of state power and class agency. It is derived from the single model of industrialization of Britain, to the entirely different situation of India. Consequently it neglects the specificity of India s class structure, power configuration and ideological currents. The importance of the ideological commitment of certain strategically placed political leaders to socialism in the context of a different balance of class forces that essentially excluded the capitalist class from state power.

Mahalanobis Model Mahalanobis model belongs to the general family of economic models encompassed under Harrod-Domar model. Mahalanobis had developed the conceptual foundation of his model independently without any awareness of the Harrod-Domar model, but when it was brought to his attention he graciously acknowledged its temporal priority. The H.D. model is focused on capital accumulation as the engine of economic growth. Its aim was to determine for developed economies the rate of investment necessary to assure such increase in national income so as to provide full employment. Mahalanobis model focused on the operational requirements specifically of the Indian case without any larger claim of contribution to economic theory.

Mahalanobis(contd.) Mahalanobis argued that India needed to increase its annual rate of investment as a proportion of national income from 5 per cent to 10 or 11 per cent if it wished to double its per capita income in 35 years. In this model the entire economy was treated as a single sector. But in 1953, Mahalanobis went on to elaborate the single sector model into a two-sector one, differentiating the two sectors on the basis of whether they produced investment goods or consumer goods, along with making the implicit assumption of a closed economy. With considerations of long-term development as its foremost preference the model gave preference for the investment goods industries sector. In this, the model was similar to the Feldman model developed in the Soviet Union in 1928.

Elaboration of the Two-sector Model For purposes of allocation, the two-sector model was now further elaborated, so that while the basic investment goods industries sector was retained as such, the consumer goods sector was further subdivided into three sectors: i. Factory consumer goods industries; ii. Household industries, including agriculture; and iii. Services. Foreign trade did not figure in either the architecture of the model or its details.

The Rationale Behind Such Export Pessimism One of the main objectives in the thrust for the investment goods industries was not just to assure long-term development but also to cut down, indeed eliminate, dependence on the outside world in the future. This stance of attempted autarchy has been attributed to what has come to be characterized as export pessimism or export fatalism on the part of Indian planners. After favouring two of the three components of development pattern as regards to the third component i.e. ownership, Mahalanobis felt it was a matter of choice for party and government policy. However, Mahalanobis himself endorsed the choice for state ownership of heavy industry.

Perceptions During the Second Plan Regarding Structural Backwardness The perceptions prevalent during the second plan about the underlying main causes of structural backwardness were as follow: i. The extreme shortage of material capital as the basic constraint on development; ii. The low level of savings as a factor retarding capital accumulation; iii. The presence of structural limitations on converting savings into investment even if savings could be raised; and iv. The necessity of industrialization in order to employ underemployed rural labour, since agriculture faced long-term diminishing returns.

A Direct Link Between Perceptions and Planning Chakravarty sees a direct link between the perceptions mentioned above and planning through the medium of economic theory. Chakravarty also emphasizes that there was a wide consensus which was prevalent on these perceptions at that point in time Chakravarty avers that Indian planners operated on the assumption of a low elasticity of export demand accompanied by a system of strict import allocation. Thus they were in reality operating on the assumption of a nearly closed economy. However, he underlines the need to raise the real savings rate that led Indian planners to accord primacy to a faster rate of growth in the capital goods sector.

Origins of Indias Economic Strategy- Bimal Jalan s View In his attempt at understanding the origins of India s economic strategy, Jalan focuses on several aspects: the emphasis on industrialization and the corresponding neglect of agriculture, the inward orientation of the strategy and its relationship to export pessimism, and the activist role of the state as entrepreneur. Jalan explains that the initial choice of the strategy was a response to the prevailing intellectual perception of the initial conditions and the role of the state in development. India s own political and social history also supported the case for an inward-looking strategy of industrialization, with the state in command. Importantly, he underlines that foreign trade had only a small place in Indian planning, because it was believed that the trade regime had a built-in bias against underdeveloped countries and partly because of the intellectual conviction that export prospects were severely limited.

Colonial Experience and the Call for Swadeshi Jalan links Indian perception to economic thinking of the time. He argues that these perceptions were widely shared by political leaders and Indian intellectuals of the time. Jalan, then, refers to several other factors as strengthening India s determination to build a self-reliant industrial base. The colonial experience was sufficient to reinforce the belief that the free-trade regime was biased against India and other developing countries and could not be relied upon to generate growth and improve living standards. The call for swadeshi therefore became an important element in the political struggle against colonial rule. It was inevitable that after independence the building of an indigenous manufacturing base should become an important objective of economic policy. This strategy was also an aspect of the struggle for economic and political independence from the UK and other Western powers.