Seminar on Baby Removal Prevention Project: Insights and Solutions

This seminar delves into recent trends and contextual factors affecting removal practices, particularly among Māori communities. It explores strategies to prevent removals of infants at birth or shortly after, emphasizing the importance of addressing societal inequities. With a focus on organizational structures, service design, and policy, the project aims to create systemic change through partnerships with whānau and Māori entities, guided by Te Tiriti/the Treaty. The data presented highlights disparities and the need for radical reform to better support vulnerable families.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Community feedback seminar Baby removal prevention project Nau mai, haere mai Emily Keddell Social and Community Work programme Kerri Cleaver Tiaki Taoka Ng i Tahu Luke Fitzmaurice - PhD candidate RA - Te Aup uri

This seminar covers Ko t nei korero e p ana ki What do recent trends suggest about removal practices? What are the wider contextual factors which lead to inequalities in removal rates, including the overrepresentation of M ori? What do professionals working with wh nau in the community say helps prevent removal? What are wh nau perceptions of what helps avoid removal? What are the overall lessons for organisational structures, service design, policy and practice? 2

What were the aims? He aha ng wh inga? To find out what helps prevent babies being removed at or soon after birth. Why is this important? - Significant effects on babies, mothers, fathers, wh nau, wider family members and society - Refracts social inequities of ethnicity, class, gender and disability - Raises important discussions about the role of the state in family life - Was increasing between 2015 18, stabilized, then dropped sharply 2019 20. - Wanted to move beyond describing problem to finding what might help it. 3

Many interrelated conceptual, ethical, cultural and structural issues Given the vulnerability of infants and their mothers in the immediate post-natal period, issuing care proceedings at or close to birth is fraught with moral, ethical and legal challenges and without effective, timely assessment and support during pregnancy, intervention at birth is likely to be poorly planned and can result in instability for the new baby and huge distress for family members (Broadhurst, Alrouh, & Mason, 2018, p.8, Born into Care report). Radical disruptive change will only be created if systemic change is undertaken. Te Tiriti / the Treaty must be used as a framework partnering with wh nau, hapu , iwi and M ori entities as determined by M ori (Irwin, 2020, p.5, Te Kuku O Te Manawa - Moe arar ! Haumanutia ng moemoe a ng t puna m te oranga ng tamariki). 4

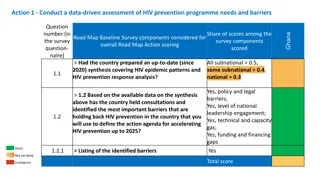

Trends 120 6 100 5 Rate per 10,000 births 80 4 Rate/popn* 60 3 Maori removed/Maoribirths Nmremoved/Nmbirths 40 2 Disparity ratio 20 1 0 0 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Year Figure 1. M ori and non-M ori rates and disparities of babies removed unborn - 3 months old 2015 2020 5

Rates of <12 mth baby removal by mean deprivation and region, 2018 7 180 160 6 Rate per 10,000 births 140 Mean deprivation level 5 120 4 100 80 3 60 2 40 Ave dep 1 20 Rate2018 0 0 Regions *Data from Oranga Tamariki, 2020, Stats NZ regional birth numbers, and NZDep2013, mapped to Oranga Tamariki sites. 65 sites were combined into regions and their mean dep levels averaged. *Auckland region combines three Oranga Tamariki regions to match regional reporting of birth numbers. 6

What did we do? Lived experiences of people on the front-line Qualitative approach with key groups: - Families who have been at risk of removal, but have avoided it, had a baby returned, or placed with an agreed caregiver (interview) - The key professional working most closely with them usually in community organisations (interview) - = case stories/studies - A range of other professionals working in the community with families who have CP system contact (focus groups) - Total = 16 profs in focus groups, plus 7 people from 3 case studies = 23 participants - Drawn from all over the country - Reference group 7

What are the contextual factors underpinning inequalities? 1. Historical: M ori are significantly overrepresented in the child protection system, and the roots of that overrepresentation lie in the legacy of colonisation. Intersections with socioeconomic status exacerbate this. Sociocultural: Cultural differences can influence children s and family s interactions with the child protection system and, consequently, the likelihood of removal. 2. Inequalities: Intersecting inequalities, affect which wh nau come in to contact with the system, how they experience the system, as well as their outcomes in both the short and long term. Gender: The child protection system is gendered mothers often describe a sense of being blamed even though in many cases they themselves were also victims of abuse. 3. 4. Policy: Changes to the child protection system are shaped by broader changes in social policy, such as the adoption of the social investment paradigm of the last five years. 5. 8

What are the contextual factors underpinning inequalities? Practice that focuses on individualised risk factors without an understanding of the wider social and relational contexts risks perpetuating the problems it seeks to solve. Many of the families most affected by child removals sit within the intersection of these overlapping contextual influences. 9

What did we find out? Themes - focus groups practitioner, organizational and wh nau factors both cause and prevent removal, and all the decision points leading up to that (decision-making ecology/continuum) Practitioner factors: prevents 1. Wh nau-centred practice orientation = advocacy, self-determination and expectation of capabilities. For M ori, includes Treaty perspective. Self-defined needs and tailored supports. Keep hold of the narrative . 2. Professional attitudes and values centred on respect and recognition of commitment to children 3. Everybody screws up enabling help-seeking through trust and long-term relationships 4. Professional skills: walking between worlds and emotional literacy (contributes to trusting and engaged relationships) 10

Chimes with wider research Wh nau control/self-determination, flexibility of services, tailored to need: I think it really depends on the wh nau and what they want. Some wh nau I ve worked with recently who have actually been successful in preventing uplift, some of them have home help at home and ACC social workers and an NGO like me and we all work together to support the wh nau because we all have our different roles but that system s not gonna work for another wh nau because they don t require that kind of support. to work around that Focus group 3 participant. Trust and capability building: I think that trust thing. Like you know, I think it is so very important and an understanding that everybody, everybody screws up and you know and celebrating the small things and understanding that sometimes it s a one step forward, two steps back but it s just around scaffolding and mitigating and making people feel ok about coming and saying I need some help Taking that sort of whakam feeling away Focus group 1 participant. data from parents and providers suggested that practices which make parents feel respected, valued, and treated as if they are knowledgeable and capable (p. 327) enhance parents' motivation to participate in services and work actively on the issues confronting their families (Kemp et al., 2014: 29) 11

Emotional literacy It s like a, there's like a bell curve .they're at their most vulnerable and probably behaving in their worst, at their height of survival brain, shall we say. And then we can have another snapshot when they're in their peak form, you know, when they ve had, oh, you know, I m engaging with this worker, and I ve entered into some rehabilitation around my drug use, and, oh my gosh, I m , lights are going on because when you ve got a stroppy social worker banging on your door, saying, hey, I m here, we ve got these concerns about you having , of course, people are going to react Key informant 1. 12

Themes focus groups continued Organisational factors - prevents 1. Flexibility, intensiveness, holistic nature and accessibility of services addresses whole wh nau issues. Poverty-aware and culturally relevant. 2. Professional collaboration for integrated response (contributes to trust and wh nau engagement) 3. Timing of notification and services offered early within a finite pregnancy, by right person Organisational factors causes 1. Racism and lack of recognition of Treaty obligations, impacts of colonisation, values of whakapapa, right to representation ie. who can speak for the child? 2. Previous child protection system contact/family history with Oranga Tamariki 3. Contact with other systems (e.g. health and other social services) 13

Previous system contact the power of the record Oranga Tamariki don t acknowledge those protective factors and those changes that have happened so if a mum has had uplift ten years prior but in that ten years, she s done drug and alcohol programmes and she s got training, in a job and she s really doing well for herself and this new pregnancy s like just a total different chapter in her life, [OT] will still go back to that ten years ago when she was ten years younger and in that different space. FocusGroup 3 participant The concerning thing for me is it doesn t need to be a current thing but it s, you know a past thing that s been there and because that family is then under some sort of radar within the systems, they re jumped up a level or two for people to react. FocusGroup 1 participant Interacts with racism, because M ori have much higher rates of historic contact/surveillance. 14

Organisational factors causes continued Child protection system interaction factors 1. Relationships between OT and other agencies: poor communication and lack of valuing of NGO knowledge and input Lack of trust towards NGOs from OT leads to lack of reciprocal trust from wh nau to OT . Focus Group 3 participant 2. Relationships between OT and whanau: heavy-handed and unrealistic, changing expectations/timeframes (contributes to isolation and avoidance, damages trust) quite often with the babies that I ve seen and talking with wh nau, that we always see this pattern of I m not working fast enough. You know, baby after baby, I m doing my best but it s not fast enough for Child Protection and all of a sudden this baby, the final beautiful baby they re ever gonna have they are actually saying sorry, timeframe. You haven t done it in the timeframe we ve asked so therefore, that child has bonded with the caregivers, ok, and quite often it s caregivers and not wh nau and so they re out of the wh nau and wh nau is powerless, the bonding has occurred and you re not allowed to interrupt that process Focus group 3 participant 15

Whnau factors Prevents: 1. Relationships of support between wh nau and others (reduced by some OT policies) (reduced by socioeconomic stress) Causes: 1. Poverty stress and access to services (exacerbated by inaccessible services and unrealistic expectations) 2. Impacts on parenting of drug use and related mental health issues 3. Isolation and avoidance (added to by historic trauma/system contact and authoritarian, unrealistic expectations, fragmented service provision and negative expectancies ) 16

Making connections: family support in socioeconomic and historical context saying to wh nau we believe you can do this and we believe that you have the skills in your, not just yourself but your whole wh nau can support you with that and the resources to support families to do that for themselves, it s really tricky, you know, that often they are families that are struggling financially or they are struggling for housing reasons or other social things happening in their family which mean that the wider wh nau are not as available as they would once have been we can become, I guess, part of that extended wh nau of support people for the families Focus group 1 participant So equity, lots more brought in so that the resources are there.. So they don t have to worry as much, you know, wh nau wanna be there but they can t afford to be there. They re exhausted, they have other things they need to do processes should make it easier so they can focus on what s important ... You know, how horrible is it to say I really wanna focus on this but I can t afford to. I don t know how I can t make ends meet already Focus group 1 participant. 17

Informal support in historical context For us, having access to good support services whether that s in an NGO space or whatever is helpful for our wh nau but also their natural supports and they ve got to find those positive ones out in the community but with saying that, if you ve got gang connections, OT won t see that as good supports but we know gang members can be good parents, uncles, aunties and it s not acknowledged by Oranga Tamariki that they can parent well, which is unfortunate an uncle is an uncle, you can t help who your wh nau is and you know, the more people that love a child, the better and we do have, you know, conversations with the wider wh nau to see what they are like Focus group 3 participant just looking at some cases we ve had recently that there are parents coming through now and they ve been CYFS kids themselves so they ve been removed from wh nau and Iwi and hapu and now they re having their own babies and they re still in that OT space and Oranga Tamariki are saying things like where are your natural supports and we re saying well you ve taken them all away cause you removed that child, that parent when she was a child from her natural supports Focus group 3 participant 18

Kelly, Deb and Toni: Dont go down without a fight Case story one - k rero tuatahi https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/prevention/case-studies/ Key themes: Strategic advocacy, rights-based practice regarding disability, accurate assessments, support not surveillance, collaboration between OT and other profs, residential options, multiple meanings of wh nau, be prepared. Toni: There is a huge need for a cultural and policy shift within Oranga Tamariki in terms of how they understand and respond to disability [the] narrow focus really has terribly negative impacts on people who, you know, require support to participate in a meaningful way . serious decisions made that have lifelong effects on parents and children, they are outdated, and unfounded beliefs and attitudes about intellectual disability It s seen as a risk factor full stop, without considering, you know, what are the layered supports or arrangements that might [be needed]? It s the fact that the relationships and the bond can endure. Kelly s message for other parents: Don t give up. Don t go out with, don t leave without picking up a fight. Deb: I just felt that they didn t always treat her like a reasonable human being that has equal rights as you and I do. 19

Tracey and Simone: It was pretty much last warning Case story two k rero tuarua Key themes: Intensive support service, empowerment and focus on own goals, mediators of meaning, relationship, holistic service (anything you need/ stress reduction focus), intrinsic motivations, M ori practitioner for M ori wh nau, changing OT expectations. Simone: We hear it over time and time again with our whanau, that they re not, they re just not transparent enough They say you ve got to do all of this and then they keep moving the goal post all the time. Tracey: Don t focus on CYFS, they re not really that important. Focus on what you know you have to do for your children and for yourself, because only you know what s good for you and your kids just make the changes, be ready to be open to change. The level of comfort that M ori wh nau have when working with a social worker who is also M ori is often different to what they would have with a non- M ori worker, and that relationship can be make or break. Part of this is ensuring that there are enough M ori workers to work with M ori wh nau . 20

Katrina and Sarah: That doesnt make sense, because the children need to go back to their parents, you know? Case story three k rero tuatoru Key themes: Drug rehab, trauma-informed, intensive/holistic service, coaching re professionals, relationship of trust leads to honesty (needs time), concrete help, rebuilding confidence, OT workers over-stretched, accurate assessments (not only on paper), focus on parenting support if children are to stay/return. By M ori, for M ori services. Katrina: They only help the children apparently That doesn t make sense because the children need to go back to their parents, you know? Sarah: Addressing those stresses providing a safe environment can encompass a whole other thing, budgeting, you name it, all sorts of things. You know, it s not just parenting. Katrina: Maybe not always judging the situation by the paper, like maybe being more involved in people s recovery and that too. 21

Addressing direct and decision-making ecology issues Some issues can (but not always) affect parenting capacity in some way: Other issues have nothing to do with parenting capacity, but affect systems responses and decision- making processes within the dm ecology (Fluke etal., 2014): - Drug addiction - History of trauma - Poorly coordinated services - Stress - Authoritarian/superficial practice (recorded history reliance) - Poverty - Lack of inclusion of family perspective or NGO workers - Disability - Intimate partner violence - Lack of resource for intensive provision - Lack of community supports/ isolation - Poor communication = direct issues - Racism/classism/sexism/ableism = need early, integrated, rights-based, intensive/holistic services by right people + - = decision ecology - = need strategic advocacy, critical resistance, reclaim the narrative community development and social protections 22

Structural and contextual Implications Connected systems of responses to needs Consensus between NGO and govt services on assessment and interventions Parent and baby options Intensive support options Available in location Community based Accessible and available intensive, accessible holistic services Te Ao M ori Poverty lens Building Community Provisions Capacity/ capability or devolution Te Tiriti More M ori organisations Obligations to delivery, Article 2. 23

Implications for Practice- internal Wh nau Centred Practice P Harakeke Model- work with the whole wh nau Contracting that allows NGO s to remain involved, long term relationships Intrinsic links inherent in wh nau connections to mokopuna Advocacy walking between worlds Mediation between state and wh nau Wh nau directed Having hope for the wh nau Building confident parents Understanding disempowerment Reasonable timeframes Trust, Respect and Transparency Practitioner Expertise Parental knowlege Practice experience Building wh nau networks Multi-generational effect Wh nau, hapu , iwi 24

Implications for Practice- external relationships Oranga Tamariki/ NGO relationships Working together collaboratively Parellel sharing power (OT NGO Trust community expertise Transparency wh nau mother) Mediation and advocacy Complex multi-system 7AA obligations Relationships Focus on support, preservation and respect Coordinated access to resources Widening contractual obligations Meeting needs Recognition of system racism Blantant versus subversive Worldviews and definitions Supporting wh nau to control their narrative 25

Kia ora m taringa! He p tai? Emily.keddell@otago.ac.nz Kerri.cleaver@tiaki.taoka.nz Luke.Fitzmaurice@otago.ac.nz https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/prevention/

References Broadhurst, K., et al. (2018). Born into Care: newborn babies subject to care proceedings in England. London, The Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. Fluke, J., et al. (2014). Decisions to protect children: A decision-making ecology. In Korbin, J. E. & Krugman, R. (eds). Handbook of Child Maltreatment. Springer. Kemp, S. P., Marcenko, M., Lyons, S., & Kruzich, J. (2014). Strength-based practice and parental engagement in child welfare services: An empirical examination. Children and Youth Services Review 47: 27-35 Masson, J. & Dickens, J. (2015). Protecting unborn and newborn babies. Child Abuse Review 24(2): 107-119. Office of the Children s Commissioner (2020) Te Kuku O Te Manawa - Moe arar ! Haumanutia ng moemoe a ng tu punam te oranga ng tamariki. OCC, Wellington, Aotearoa. 28