Respiratory Diseases in Cattle: Causes, Infections, and Management

Respiratory diseases in cattle primarily stem from infectious agents such as infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and Pasteurella spp. These diseases compromise the defense mechanisms of the body, leading to infections like pneumonia and pleuropneumonia. Viruses, mycoplasmas, and bacteria like Histophilus somni are common culprits, affecting young calves and posing significant economic challenges. Immunity in young cattle is poor, making vaccination regimes limited, and antibiotic therapy costly. Eradication efforts for diseases like contagious bovine pleuropneumonia face organizational hurdles in developing countries.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Respiratory Disease* *COLOR ATLAS OF DISEASES AND DISORDERS OF CATTLE T H I R D E D I T I O N Roger W. Blowey, A. David Weaver, Elsevier 2011 1

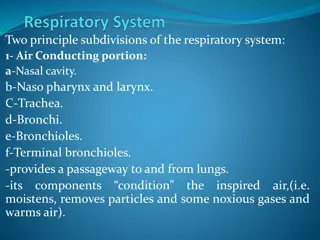

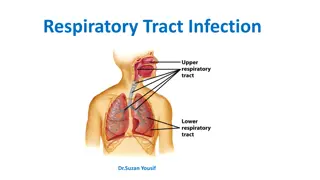

Respiratory disorders Although respiratory diseases have a variety of causes, infectious agents predominate, e.g., infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) is caused by a herpesvirus that can affect several body systems. 2

Respiratory disorders A second group of important respiratory infections is caused by Pasteurella spp., usually following exposure of young cattle to stress (hence the alternative name for pasteurellosis, shipping fever ). Both Mannheimia haemolytica serovar 1 and P. multocida are normal inhabitants of the upper respiratory tract and in particular the tonsillar crypts. 3

Respiratory disorders In order to permit colonization of the lungs, stress or a primary viral infection such as bovine virus diarrhea/mucosal disease (BVD/MD), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), or parainfluenza type 3 (PI-3), must compromise the defense mechanisms of the body. 4

Respiratory disorders A third respiratory infection, termed endemic or enzootic calf pneumonia, affects groups of young calves and is of major economic importance. Both viruses (e.g., PI-3, BVD, IBR, RSV, adeno- and rhinoviruses) and mycoplasmas may be primary agents, but the etiology of many outbreaks remains uncertain, since bacterial colonization by Pasteurella spp. tends rapidly to supervene. Consequently, the primary virus infection may have been cleared by the time of autopsy. The role of Chlamydia is unclear. 5

Respiratory disorders Histophilus somni is of major importance as a cause of suppurative pneumonia (9.29), but, having effects on several organ systems, it is presented as infectious thromboembolic meningoencephalitis. 6

Respiratory disorders Respiratory diseases in young cattle are of great economic importance, since their immunity to many etiological agents is poor and vaccination regimes therefore have severe limitations. Antibiotic therapy can be very costly, and recovering cattle often show poor weight gain. Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP) is a problem in many developing countries, such as parts of Africa, India, and China, where eradication through a slaughter policy and vaccination programs presents major organizational problems. 7

Respiratory disorders Chapter 5 is divided into infectious (viral, bacterial, and other agents) and noninfectious (allergic, iatrogenic, circulatory, and physiological) etiology. Where appropriate, cross-reference is made to other sections for lesions affecting other systems, e.g., both calf diphtheria and laryngeal abscessation are shown in the neonatal chapter, even though they sometimes occur in older animals. 8

Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) Infectious disorders; Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) ( rednose ) Etiology and pathogenesis: IBR is caused by bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1). In addition to respiratory disease, other major syndromes due to BHV-1 include abortion and genital tract infections. BHV-1.1 is the respiratory subtype, BHV-1.2 the genital subtype, and BHV-1.3 the encephalitic subtype. The last-named was recently reclassified as BHV-S, a distinct herpesvirus. 9

Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) Infectious disorders; Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) ( rednose ) Etiology and pathogenesis: Pasteurella spp. are common secondary invaders. BHV-1 can cause severe disease in young calves involving pyrexia, ocular and nasal discharge, respiratory distress, and incoordination, leading to convulsions and death. 10

IBR, Clinical features: The common respiratory form of IBR has major clinical signs involving the nostrils (hence the alternative name of rednose ) and the eyes. Feedlot cattle are at particular risk. Within a group of young cattle, several individuals may be affected simultaneously with epiphora and depression. 11

IBR, Clinical features: Severely affected animals, are dull, somnolent, anorexic with a tucked-up belly, and have a mucopurulent nasal discharge, nasal mucosal congestion and lymphadenopathy, and sometimes a harsh cough. 12

IBR, Clinical features: The palpebral conjunctivae may be intensely injected or congested in the acute stage. Characteristic, small, raised, red plaques are visible near the lateral canthus. 13

IBR, Clinical features: Secondary infection may lead to a purulent oculonasal discharge as well as a typical purulent IBR conjunctivitis, without blepharospasm. 14

IBR, Clinical features: Autopsy examination of this animal reveals a severe necrotizing and hemorrhagic laryngotracheitis. 15

IBR, Clinical features: Another severe case is shown in 5.5. 16

IBR, Clinical features: In severe cases the nasal septum sloughs its necrotic mucosa. Epistaxis may follow the rupture of mucosal vessels. 17

IBR, Clinical features: Balanoposthitis can occur with bovine herpesvirus 1 infection. The separated vulval lips reveal the multiple, discrete pustules of infectious pustular vulvovaginitis (IPVV). The similarity of the male and female lesions is obvious 18

IBR, Differential diagnosis: The characteristic signs, pyrexia, and eye lesions especially make diagnosis simple in uncomplicated cases. It is preferable in a field outbreak to attempt virus isolation for confirmation, or demonstration of a rising antibody titer. Bulk milk antibody tests give a simple and inexpensive indication of herd status. 19

IBR, Management: Many cattle only with eye lesions will recover spontaneously, though there is a subsequent risk of poor fertility and an increased abortion rate. Antimicrobial therapy is needed to prevent or treat secondary infections (Pasteurella). Breeding cattle, replacement heifers, and calves may be vaccinated from 2 months old with intramuscular or intranasal administration of modified live vaccines. 20

IBR, Management: Cattle entering a feedlot should be immunized 2 3 weeks before admission, but the immune response is poorer. IBR is being successfully eradicated in some European countries by serological testing and either culling reactors or strict maintenance of a two-herd system. 21

Pasteurellosis ( shipping fever , transit fever ) Definition: pneumonic pasteurellosis is frequently caused by Mannheimia haemolytica serovar 1 biotype A, sometimes by P. multocida or Histophilus somni, which are all normal inhabitants of the upper respiratory tract. Often pasteurellosis is secondary to respiratory viral infections. 22

Pasteurellosis, Etiology and pathogenesis: after stress, e.g., transport and/or viral infection, these organisms proliferate rapidly and extend into the trachea, bronchi, and lungs. A. pyogenes is a frequent secondary invader. 23

Pasteurellosis Clinical features: Severe respiratory signs were evident, with dullness and anorexia, pyrexia, and a moist cough. The cranioventral lung fields reveal wheezing sounds on auscultation. An expiratory grunt is possible. 24

Pasteurellosis severe respiratory distress (5.8), with the head and neck extended, open- mouth breathing, and froth on the lips, is obvious in this calf, which died an hour after the photograph was taken. 25

Pasteurellosis Another tucked-up beef steer (5.9) shows severe dyspnea as open- mouth breathing. 26

Pasteurellosis At autopsy examination of another calf (5.10), in addition to froth in the major bronchi, the apical and cardiac lobes are typically dark red, slightly swollen, firm, contain microabscesses. 27

Pasteurellosis The diaphragmatic lobes are normal. Such lungs may have fibrin deposits on the pleural surface. Lung changes tend to be symmetrical. In 5.11 the pneumonic areas of the apical and cardiac lobes show scattered, pale yellow abscesses. 28

Pasteurellosis Differential diagnosis: diagnosis depends on bacterial culture from material derived from the lower respiratory tract, or from lung tissue at autopsy. Antibiotic sensitivity testing should be done. Serology is unhelpful in diagnosis. 29

Pasteurellosis Management: prompt and aggressive antibiotic therapy should extend well beyond the resolution of clinical signs in affected calves to minimize the development of chronic lung abscessation. 30

Pasteurellosis NSAIDs are important when lung congestion and respiratory signs are severe. Pasteurella toxoid vaccines are very effective for control, but several doses may be needed in young calves where the immune response is poorer. 31