Rabindranath Tagore's Impact on International Education Discourse

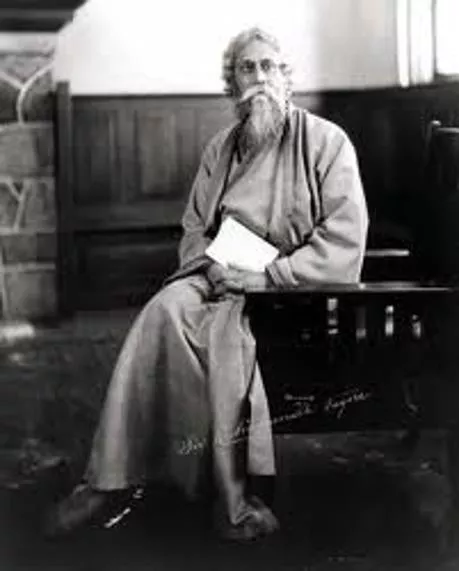

Rabindranath Tagore, a renowned figure from Bengal and the first non-European Nobel Prize recipient, played a significant role in promoting international education and world citizenship. His poetic works, particularly "The Gitanjali," reflected his universal outlook. Tagore's establishment of the International School in Santiniketan in 1901 and his belief in cultivating world citizenship through education showcase his enduring influence on global educational practices.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Rabindranath Tagore's Place in the History of International Education: A Case Study of the Early Discourse* Bob Sylvester Professor of Global Literacies Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, MA 02325 USA *based on forthcoming book, Cultivating Their Humanity: A History of International Education (1851-1950)

First Non-European / Nobel Prize Rabindranath modern day polymath from Bengal was by clearly of the cosmopolitan tendency, a internationalist and a strident anti-nationalist. Tagore, a disposition universal Widely known in the West after 1912 when his works were promoted among the British and continental literati.

The Gitanjali Among the poetic verse that Tagore (1913) was recognized for by the Nobel Committee was The Gitanjali with an Introduction written by W.B. Yeats. Tagore s contained a poetic ecology evocative of Walt Whitman s Leaves of Grass. Stream of Life

Stream of Life The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world and dances in rhythmic measures. It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the earth in numberless blades of grass and breaks into tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers. It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death, in ebb and in flow. I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this world of life. And my pride is from the life-throb of ages dancing in my blood this moment. (Gitanjali 69, p. 86.)

International School Directly developing School grounds school established in 1901 in Santiniketan, West Bengal. involved an (university) of by 1921 International near ashram the and an Extensive correspondence during his long career, much pronounced his creed. international of global which civic

Practice of World Citizenship Rabindranath interest educational practice of world citizenship was not limited to expression in essays, poems or staged productions. Tagore s in supporting an He founded a modest boys school called Shantiniketan, started on a small scale in 1901 with five pupils and five teachers.

International Educations Meaning Tagore believed that international education was the means by which cultures, arising geographical locations, would meet and speak to each other. (Gutek, 1993, pp. 23-4) in different 15 years after opening the Boys School Tagore made concrete plans for his university. In 1916 in southern California Tagore thinking about establishing an international university. international formalized

Sir Michael Sadler He Sadler, Calcutta Commission in 1917. welcomed the Sir Michael of University Head the It was a meeting that gave birth to a direct friendship. and abiding

Where the world meets in one nest His university was to be called Visva- Bharati. Sanskrit word for universe with the name of the Hindu goddess of learning and the ancient traditional name for India. The motto of the university, also from a Sanskrit phrase: Chavatyekanidam or Where the world meets in one nest. Yatra Visvam

James Cousins Next three years spent with fundraising activities the world. around At the outset of the fund-raising period, Tagore was invited to speak to students at a college just north of Bangalore by James Cousins, the Irish poet and friend of Yeats who was serving as its College President.

National Systems of Education In his talk, Tagore painted a portrait of the tension that existed when national systems and philosophies of education are imported, in toto, into other nations: What I object to is the artificial arrangement by which this foreign education tends to occupy all the space of our national mind and thus kills, or hampers, the great opportunity for the creation of new thought by a new combination of truths. It is this which makes me urge that all the elements in our own culture have to be strengthened; not to resist the culture of the West, but to accept and assimilate it. It must become for us nourishment and not a burden. We must gain mastery over it and not live on sufferance as hewers of texts and drawers of book-learning. (Dutta and Robinson, 1995, p. 222)

Meeting the East and the West Tagore acknowledged that he sought, through the university, a meeting of the East and the West. The university would have among its aims, to study the mind of man in its realization of different aspects of truth from adverse points of view To seek to realize in a common fellowship of study the meeting of East and West, and thus ultimately to strengthen the conditions of world peace through the establishment communication of ideas between the two hemispheres. (p.168) fundamental of free

1921 University Established The presence of the university was launched in 1921. viewed his practice as directly tied to a civilization-building process: formal institutional Tagore educational I believe the unity of human civilization can maintained by the linking up in fellowship and cooperation of the different civilizations world. (Periaswamy, 1976, p. 122) be better of the

League of Nations Handbook University League of Nations (1921) Handbook, promulgated as a supporter of the meeting of East and West: cited in the clearly L Universit Santiniketan essaie de s harmoniser avec l histoire et l espirit de l Inde m me, r unissant cultures de l Asie et y ajoutant la plus haute culture que l Occident ait produit en science, philosophie et dans les arts. (p. 109) internationale les diff rentes litt rature,

Deliberate Internationalism Model was a deliberate form of internationalism, co-educational and ignored all sectarian barriers. Tagore China in 1924 with a view towards interacting with students as much as possible. (Chatravaty, 1961) visited His talks were transcribed by his personal secretary, Elmhirst, the British co-founder of Dartington Hall experiment in rural reconstruction and progressive education. Leonard K. in Devon, an

Predatory Materialist Culture Tagore challenged his Chinese student audience with the prospect of a widespread predatory materialist culture during a dark time for the world: This age to which we belong, does it not still represent night in the human world, a world sleeping while individual races are shut up within their own limits, calling themselves nations, barricading themselves, as these sleeping cottages were barricaded, with closed doors, bolts and bars, and prohibitions of all kinds? Does not all this represent the dark age of civilization, and have we not begun to realize that it is the robbers who are out and awake? The torches which these men hold high are not the lights of civilization, but only pointings to the path of exploitation. (p. 208)

Objects of Education Tagore further outlined his objects for education to the students in China: There are of course natural differences in human races which should be preserved and respected, and the task of our education should be to realize unity in spite of them, to discover truth through the wilderness contradictions. (p. 216) of their

Teachers from around the World Tagore was able to attract teachers from all around the world. In the period of 1921- 1939 educators from over a dozen countries associated with Tagore and the university. became He attracted teachers from Switzerland, USA, Italy, Hungary, England, Persia and China, France, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Scotland, Israel and Burma. Russia, Sweden, Norway,

The Unity of Education (1921) Tagore s (1921) philosophy of international education in essay, The Unity of Education . Mungazi (2001) observed that Tagore s contribution to the prospect of education lay in the Western idea of human relationships in which the West displayed an inability to importance of the existence of other cultures and their potential to contribute to the common good of humanity. (p. 80) international recognize the

Capitalism & Human Relations Tagore also objected to capitalism s mechanical treatment of human relations: The cult of the machine has produced a rift in human relationships within the West itself. The attempt to unite human beings by artificial means, as if they were pieces of paper or wood that could be gummed or screwed together, loosens the natural and creative bonds which alone can spontaneously fuse them in a deep spiritual unity. (p. 241)

Materialisms Challenge Tagore was not alone exploring a spiritual foundation beliefs. Augustus O. Thomas (1921) was soon to lead efforts for a world educational interests and wrote of an aggressive materialism : of civic federation of Even yet the world is in nervous collapse from which it will require years to fully recover. Our material structure is unable to stand alone. The nations are sorely afflicted and realize the materialistic standards are inadequate. The hope of the world today lies in the inculcation of spiritual values. (p. 181)

Religious Yet Not Dogmatic Periaswamy (1976) quoted the American philosopher Robert Ulich (1890- 1977) in validating educational-spiritual cosmos: educational Tagore s We would misinterpret Tagore s hopes for a new science of life if we did not recognize profoundly religious entirely undogmatic element. (p. 196) in them though a

Martha Nussbaum The classicist, Martha Nussbaum (2007) paid tribute to Tagore s educational successes in the context of a modern practice of cosmopolitanism: Tagore was perhaps more focused on this cosmopolitan idea, given his work on developing a universalistic religion of man. His school cultivated this idea by inviting faculty from all over the world to teach about their nation s groups, problems, and traditions and by having students learn about all the major religions even celebrating their holidays. (p. 38)

Cosmopolitan Practice Tagore s cosmopolitan practice was also evident in his poetry. His award-winning poetry (Chakravarty, 1961) shows traces of the fragrance of his universal educational orthodoxy. The lure of nationalist sentiments was acknowledged by the poet, but its influence in his poetic mind was to be sublimated to the needs of the world in the context of its organic whole.

Cosmopolitan Poetry Where the mind is without fear, and the heart is held high Where the world is not broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls, Where the words come out from the depths of truth, Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection; Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habits, Where the mind is led forward by thee into Ever-widening thought and action Into that heaven of freedom, My father, let my country awake. (p.300)

H.G. Wells In Rabindranath H.G. Wells met in early June, 1930 in Geneva. a striking encounter, Tagore and The conversation 1961) reveals a shared interest in human affairs at the level of civilization: transcript of the (Chakravarty,

Tagore and Wells (Tagore) I believe the unity of human civilization can be better maintained by fellowship and cooperation of the different civilizations of the world. Do you think there is a tendency to have one common language for humanity? linking up in (Wells) One common language will probably be mankind whether we like it or not. Previously, a community of fine minds created a new dialect. Now it is necessity that will compel us to adopt a universal language. forced upon

The European Narrative Wells then placed the dominant European narrative in stark relief: The supremacy of the West is only a question of probably the past hundred years. Before the battle of Lepanto the Turks were dominating the West; the voyage of Columbus was undertaken to avoid the Turks. Elizabethan writers and even their successors were struck by the wealth and the high material standards of the East. This history of western ascendancy is very brief indeed. (Chakravarty, 1961, p. 108)

The Colonial Frame Both men then lamented the lost opportunities in education within a colonial frame of reference: (Tagore) And then, the channels of education have become dry river beds, the current of our resources having systematically been diverted along other directions. (Chakravaty, 1961, p. 108.) While H.G. Wells would continue writing about his utopian visions, Tagore would persevere in his attempts to human culture in practical educational terms. develop a new

Professor Gilbert Murray The theme of education developing an international mind was a major preoccupation in the 1920s and 1930s. Rabindranath Tagore praised the concept as a Giant Killer which, though small in size, was very much a real force in the global society. Professor Gilbert Murray, the Oxford University Greek classicist and chair of the Committee on Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations, embraced a cosmic framework for understanding the role of education in building a new world.

An International Mind Murray (1929) plotted out the central features involved in education that would develop such an international mind: And I strongly suspect that the surest way both to a good education and to international citizenship is to have one s studies grouped around some central purpose. Such a central purpose, to be at all satisfactory or enduring, must help or at least be consistent with the good of the whole; above all it enthrones the principle of cosmos above the turmoil of momentary desires and egotisms. (p. 215)

Murray and Tagore Tagore engaged in correspondence with Murray in September 1934, an exchange which reflected the dilemma of education in the Interwar Period: international I find much that is deeply disturbing in modern conditions. conscious of the inescapable moral links which hold together the fabric civilization. I cannot afford to lose my faith in the inner spirit of man, nor in the sureness of human progress. Man, in his essential nature, is spiritual and not entirely materialistic. (Mungazi, 2001, p. 83) I am more inevitable and of human

Murray and Tagore Murray responded in an openly personal manner (Murray and Tagore, 1935) remembering the late Madame Curie who he witnessed involved in the work of the Intellectual Co-operation and who sought to remedy the destructive and narrow impulses of intellectual leaders displayed during WWI. These inspiring thoughts were present in Murray s letter when he wrote: ...there is a higher task to be attempted in healing the discords of the political and material world by the magic of that inward community of spiritual life which even amid our worst failures reveals to us Children of Men our brotherhood and our high destiny. (p. 105)

Fabric of Civilization Tagore then answered with equally personal and lofty sentiments, filled with a sense of anguish over the immensity of the educational work to be done: I am in complete agreement with you again in believing that at no other period of history has mankind as a whole been more alive to the need of human co-operation, more conscious of the inevitable and inescapable moral links which hold together the fabric of human civilization. (p. 106)

Murray at the WFEA A few years earlier at the WFEA World Conference in Geneva, Gilbert Murray (in Ryan 1929a) sought an ultimate educational purpose beyond self-gratification. In speaking of the fundamental flaws of most modern systems of education he observed: In wishing to remove the element of compulsion or authority which was excessive in some older systems, they have come perilously near accepting the individual s momentary desire as the standard by which all values are to be judged. (p. 979)

Coin of the Realm Tagore s legacy as a champion of world citizenship education may through his school efforts. in be viewed international His Murray underlying belief in human unity and world citizenship as the coin of the realm in the building of such a human civilization. correspondence highlights with his

Death in 1941 Rabindranath Tagore, the 1913 Nobel Laureate in Literature and founder of an university in the Calcutta in 1921, died after a prolonged illness in 1941. international outskirts of This showed destructive legacy of the of the British colonial education regime for India was awarded an honorary degree by Oxford University in 1940 for all of his achievements in the arts and humanities. Renaissance a man who the loathing for

Tribute by Montessori Later in his life, Tagore attracted the collaboration and association of the international educator Maria Montessori who visited Shantiniketan in 1939. Upon his death, she wrote (Dutta and Robinson, 2001) to Tagore s son: There are two kinds of tears, one from the common side of life, and those tears everybody can master. But there are other tears which come from God. Such tears are the expression of one s very heart, one s very soul. These are the tears which come with something that uplifts humanity, and these tears are permitted. Such tears I have at this moment. (p. 196)

Tagore as World Citizen Tagore was an exemplar of world citizenship in the 20thcentury. But the political class of India was slow to appreciate Tagore s world standing. He was viewed with greater admiration appreciation around the world rather than in India. and

Indias Internationalist Jawaharlal Nehru, (Periaswamy, 1976) the first prime minister of India, viewed Tagore s legacy within a global lens: He has been India s internationalist par excellence, believing international co-operation, taking India s messages to other countries It was Tagore s immense service to India, as it has been Gandhi s in a different plane, that he forced people in some measure out of their narrow grooves of thought and made them think of broader issues affecting humanity. was the great humanist of India. (p. 206) and working for Tagore