Overview of Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide Practices and Challenges

This presentation by Dr. Marie Nicolini provides an overview of current practices and challenges related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Covering the definitions, terms, and controversies surrounding these practices, the talk emphasizes the evolving legal landscape and the global relevance of this complex bioethical issue.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

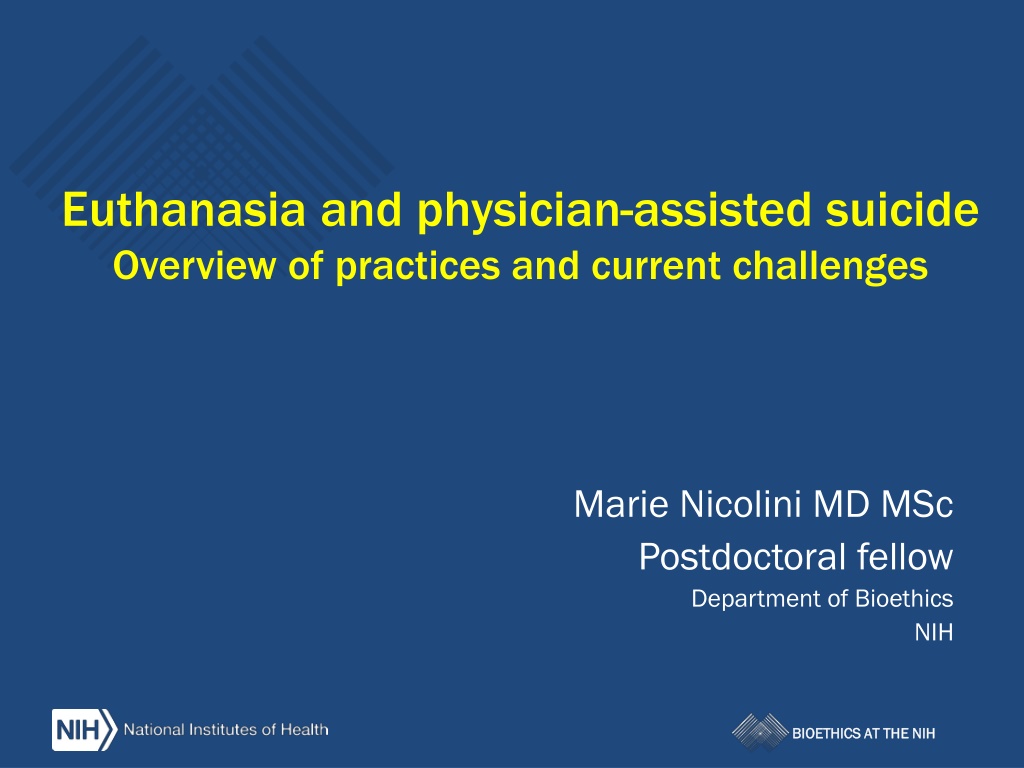

Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide Overview of practices and current challenges Marie Nicolini MD MSc Postdoctoral fellow Department of Bioethics NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Disclaimer The views expressed in this talk are my own. They do not represent the position or policy of the NIH, DHHS, or US government BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

About me 2005-2012: Medical school (KU Leuven, Belgium) BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

2012-2017: Residency in adult psychiatry (KU Leuven) 2012-2014: Erasmus Mundus Master in Bioethics 2015-2016: fMRI research in patients with dementia BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

2017-2018: Visiting scholar, Georgetown University 2018-Present: NIH Postdoctoral fellow, Department of bioethics BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Why this topic? Timely, global issue Remains controversial Rapidly changing laws BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Some terms and definitions Often used terms Euthanasia and/or assisted suicide (EAS Euthanasia and/or assisted suicide (EAS) Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) Physician-assisted death (PAD) Physician aid-in-dying Death with dignity Hastened death Medical assistance/aid-in-dying (MAID) Used in Europe & international literature Used in the US Used in Canada BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Some terms and definitions But all have detractors because Not all places require physicians Suicide has descriptive as well as negative meaning Palliative care can be aid in dying PAD does not distinguish between euthanasia and PAS Etc. etc. BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Overview for today Part 1: Introduction Part 1: Introduction Different end-of-life options EAS around the world Part 2: The practice in the Netherlands Part 2: The practice in the Netherlands EAS for psychiatric disorders EAS for dementia Part 3: Implications for the US Part 3: Implications for the US Debate about EAS in the non-terminally ill Conclusion & future directions BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Overview for today Part 1: Introduction Part 1: Introduction Different end-of-life options EAS around the world Part 2: The practice in the Netherlands Part 2: The practice in the Netherlands EAS for psychiatric disorders EAS for dementia Part 3: Implications for the US Part 3: Implications for the US Debate about EAS in the non-terminally ill Conclusion & future directions BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Different end-of-life options General category Specific category Normal medical practice Refusal of treatment Withholding/withdrawal futile life-sustaining treatment Pain relief with potential life-shortening effect Palliative/terminal sedation Tolerated Voluntarily stopping eating and drinking Termination of life or assisted suicide Physician-assisted suicide Voluntary active euthanasia [Non-voluntary euthanasia] Griffith, 2008 BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Different end-of-life options General category Specific category Normal medical practice Refusal of treatment Withholding/withdrawal futile life-sustaining treatment Pain relief with potential life-shortening effect Palliative/terminal sedation Voluntarily stopping eating and drinking Physician-assisted suicide Tolerated Termination of life or assisted suicide EAS Voluntary active euthanasia [Non-voluntary euthanasia] Griffith, 2008 BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Euthanasia in 96% of Dutch EAS cases RTE,2018 BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Overview for today Part 1: Introduction Part 1: Introduction Different end-of-life options EAS around the world EAS around the world Part 2: The practice in the Netherlands Part 2: The practice in the Netherlands EAS for psychiatric disorders EAS for dementia Part 3: Implications for the US Part 3: Implications for the US D Debate about EAS in the non-terminally ill Conclusion & future directions BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Historical context in the US Vacco Vacco v Quill (1997 v Quill (1997) US Supreme court ruling 1) drew sharp distinction between withdrawal of life- sustaining treatment and PAS 2) no need for PAS, since there is terminal sedation 3) no constitutional right to PAS, hence no constitutional protection Leaving it up to the states to regulate Oregon first US state to legalize PAS in 1997 BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

United States: 9 states + DC 1997 Oregon (Death with Dignity Act) 2009 Montana (PAD lawful by State Supreme Court ruling) 2009 Washington (Washington Death with Dignity Act) 2013 Vermont (Vermont Patient choice and Control at End-of-Life Act) 2016 California (End-of-Life Option Act) 2016 Colorado (Colorado End of Life Options act) 2016 D.C. (Death with Dignity Act) 2018 Hawaii (Our Care, Our Choice Act) 2019 New Jersey (Medical Aid-in-Dying for the Terminally Ill Act) 2020 Maine (Maine Death with Dignity Act) BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

United States: 9 states + DC Legal criteria For terminal illness terminal illness only: 6 months of expected life or less End of life boundary Medical boundary No requirement of assessment of suffering Medically assisted assisted death: prescription for medication Similar in past proposed UK bills BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

0.46% of all deaths in Oregon 90% in hospice Most 65 years or older (79.2%), and most had cancer (62.5%) 97% white, 1.2% Asian 55% with post-high school degree BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Top 3 reasons for request in Oregon (As reported by doctors; DWDA report 2018) 1) Loss of autonomy (91.7%) 2) Decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (90.5%) 3) Loss of dignity (66.7%) Stable over the years, across jurisdictions also. BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

California End of Life Option Act 2017 data, N=374 deaths 90+% over 60 y old Race and ethnicity: 89% white 5.1% Asian 3.9% Hispanic 0% Black 49% with some post high school degree [cf 39% of population] [cf 13%] [cf 39%] [cf 6%] BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Different rationales for PAD/EAS As an end of life issue As an issue of relief of suffering As a matter of right to self-determination BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Why is it important to know about the different rationales? To understand the different laws across jurisdictions why different jurisdictions allow PAD/EAS in different populations the current debates in Europe and Canada the impact these debates may have for the US BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Legalization of PAD/EAS Countries outside the US 2017 Australia (Victoria) 2019 Western Australia 2015 Columbia 1942 Switzerland 2002 The Netherlands Belgium 2016 Canada // 2018 Hawaii 2020 Maine 2016 California Colorado D.C 2013 Vermont 2009 Montana Washington 1997 Oregon 2019 New Jersey United States BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Countries outside the US Columbia Canada Australia Switzerland The Netherlands & Belgium BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Columbia (2015) In response to 2 court rulings in 2015 Euthanasia only Terminal illness Terminal illness required Prospective permission required from review board BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Canada (2016) Voluntary request without external pressure Grievous and irremediable Grievous and irremediable medical condition a. having a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability; and, b. being in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability; and, c. experiencing enduring physical or psychological suffering person and cannot be relieved cannot be relieved in a manner that they consider acceptable d. where the person s natural death has become reasonably foreseeable natural death has become reasonably foreseeable suffering [ ] that is intolerable they consider acceptable; and, intolerable to the BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Victoria, Australia (2017) Law allows both PAS and euthanasia Terminal illness Terminal illness (6months) with exception of neurodegenerative disorder (12mo prognosis) Suffering Suffering that cannot be relieved cannot be relieved in a manner tolerable to person tolerable BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Switzerland (1942) Assisted suicide decriminalized in Penal Code Requirements Person has a consistent wish to die Person has decisional capacity Assistance is not selfishly motivated not selfishly motivated No unbearable suffering unbearable suffering requirement BUT Guidelines specify there should be unbearable suffering BUT in practice yes BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

The Netherlands & Belgium (2002) Both countries have very similar key legal criteria - Voluntary, well-considered request - Unbearable suffering Unbearable suffering - Medically futile Medically futile/no reasonable alternative Suffering Suffering- -based based jurisdictions BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Eligibility Criteria for EAS: Variability Across Jurisdictions Country/Jurisdiction Country/Jurisdiction Proximity to Death required Proximity to Death required Unbearable suffering without hope Unbearable suffering without hope Psychiatric Psychiatric EAS? EAS? No of improvement of improvement none United States (9 states+DC) Terminal illness Colombia Australia (Victoria 2019) Quebec Canada Terminal illness Terminal illness End of life* Reasonably foreseeable natural death none none none none No No No* (No) Unrelievable suffering Unbearable, irremediable suffering Unbearable, irremediable suffering Benelux countries Benelux countries Switzerland Unbearable/hopeless suffering Unbearable/hopeless suffering [in practice guideline of organizations] ? Yes Yes Yes Germany none (Yes) *Deemed unconstitutional by Quebec Superior Court in September, 2019 BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

The Netherlands & Belgium EAS are similar But have different legal history and justification Dutch EAS law derived from case law over 25y Along with professional organizations, advisory bodies Belgian EAS law consequence of a political process Was primarily intended to modify physicians behavior BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

The Netherlands & Belgium (2002) Both make no distinction between type of medical condition Hence, allow for EAS for nonterminal illness, e.g. EAS on the sole basis of a psychiatric disorder sole basis of a psychiatric disorder (psychiatric euthanasia) EAS on the sole sole basis of dementia basis of dementia But these two applications remain controversial controversial BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

2019-2020: First legal prosecutions First prosecutions since law was enacted in 2002 relate to psychiatric and dementia EAS psychiatric and dementia EAS Netherlands: advance directive case (dementia EAS) 85y old woman: current Dutch criminal court trial (August, 2019) Belgium: 2 psychiatric EAS cases G. De Troyer (64) currently investigated by European Court for Human Rights Tine Nys (38): currently investigated by Belgian criminal court (2020) BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Godelieve De Troyer (64) BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Tine Nys (38) BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Overview for today Part 1: Introduction Part 1: Introduction Different end-of-life options EAS around the world Part 2: The practice in the Netherlands Part 2: The practice in the Netherlands EAS for psychiatric disorders EAS for dementia Part 3: Implications for the US Part 3: Implications for the US Debate about EAS in the non-terminally ill Conclusion & future directions BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

A closer lookEAS in the Netherlands Why focus on the Netherlands? Long history history: prior to the EAS law in 2002, the practice was decriminalized in 1987 Law based on relevant series of cases More transparent transparent oversight system which allow for empirical research series of cases BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Legal criteria under the Dutch EAS Law of 2002 Voluntary and well-considered request Unbearable suffering with no prospect of improvement Informing the patient about prospects No reasonable alternative Physician consulted at least one independent physician Physician provided assistance with due medical care BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Legal precedents in the Netherlands 1984 1984 Schoonheim Schoonheim case ruling Principle of necessity can justify physician-assisted suicide case ruling 1994 Chabot case ruling 1994 Chabot case ruling The source of patient suffering is not relevant Psychiatric patients can make a competent request Case lead to EAS on the sole basis of a psychiatric disorder to become effectively legal in 1997 BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Legal precedents in the Netherlands 2002 2002 Brongersma Brongersma case ruling Principle of necessity does not apply to tired of life case Suffering must be based on a medical condition case ruling BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

EAS for non-terminal disorders Lots of debate.. but little empirical evidence EAS for psychiatric disorders ( psychiatric EAS ) EAS for dementia Specific challenges in relation to eligibility criteria Interpreting irremediability Interpreting unbearable suffering BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Documentary 24 & ready to die | The Economist (2015) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWWkUzkfJ4M BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Psychiatric EAS: Overview General background General background Patient characteristics Main issues in psychiatric EAS evaluations The challenge of personality disorders BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

About 1% of all EAS cases in the NL Note: About 2.4% in Belgium (2018) RTE, 2018 BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

2012 Dutch End of life Clinic Psychiatric EAS timeline 2018 Council of Canadian Academies Report 2002 2016 Canada legalized MAID# Dutch and Belgian EAS Laws 2010 First cases published by RTE* 1994 Chabot case 2015-2016 First empirical papers Belgium& the Netherlands * RTE: Dutch Euthanasia Review Committees # Medical Assistance in Dying BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Some background on the Dutch system Regional Euthanasia Review Committees Founded in 1999 All cases must be reported reported to the RTE Publish a selection of cases selection of cases on website since 2010 5 RTEs with the goal of providing uniform guidance Cases important for the development of standards and provide transparency and auditability Published a first Code of Practice Code of Practice in 2015 Review Committees (RTE) BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Some background on the Dutch system End of Life Clinic End of Life Clinic Organization founded in 2012 Provides EAS evaluation for persons whose physician refuses to perform EAS Most patients who receive EAS at the End of Life clinic are non-terminally ill Sept 2019 renamed ExpertiseCenter Euthanasia BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Estimated numbers of Dutch psychiatric EAS cases 1995 1995 2008 2008 2016 2016 Psychiatric EAS requests requests 320 500 1100 Psychiatric EAS performed performed 2-5 30 60 About 50% of psychiatrists ever received explicit requests. Majority (60-75%) of psychiatric EAS cases are performed at the End of Life Clinic End of Life Clinic (Onwuteaka et al 2017; RTE, 2016) BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Annual Reported Dutch EAS cases 2016-2018 Medical Condition Medical Condition 2016 cases 2016 cases (N=6091) (N=6091) 4137 465 411 2017 cases 2017 cases (N=6585) (N=6585) 4236 782 374 2018 cases 2018 cases (N= 6126) (N= 6126) 4013 738 382 Cancer Combination of disorders Disorders of the nervous system Other disorders Multiple geriatric diseases CV Lung Dementia Psychiatric Psychiatric 104 244 147 293 155 205 315 214 141 275 226 169 231 189 146 60 (1.0%) 60 (1.0%) 83 (1.3%) 83 (1.3%) 67 (1.1%) 67 (1.1%) NB: Occasional cases until 2010, with steady rise since 2011. NB: Occasional cases until 2010, with steady rise since 2011. RTE, 2018 BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH

Reported Psychiatric EAS cases in Belgium 2014-2018 2014 2014 2015 45 2015 43 2016 2016 27 2017 2017 26 2018 57 Number of Psychiatric EAS Total Number of EAS 1928 2022 2028 2309 2357 % of total 2.3% 2.1% 1.3% 1.1% 2.4% 2.4% FCEC, Belgium BIOETHICS AT THE NIH BIOETHICS AT THE NIH