Leibniz's Metaphysical Unity and Harmony

Leibniz's philosophical works explore the principles of unity, substance, and harmony in the universe. He delves into the relationship between matter, soul, and the existence of God, emphasizing innate knowledge, pre-established harmony, and the principles of sufficient reason. Leibniz's ideas challenge traditional views on the nature of substances, the role of perception, and the interconnectedness of all things.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

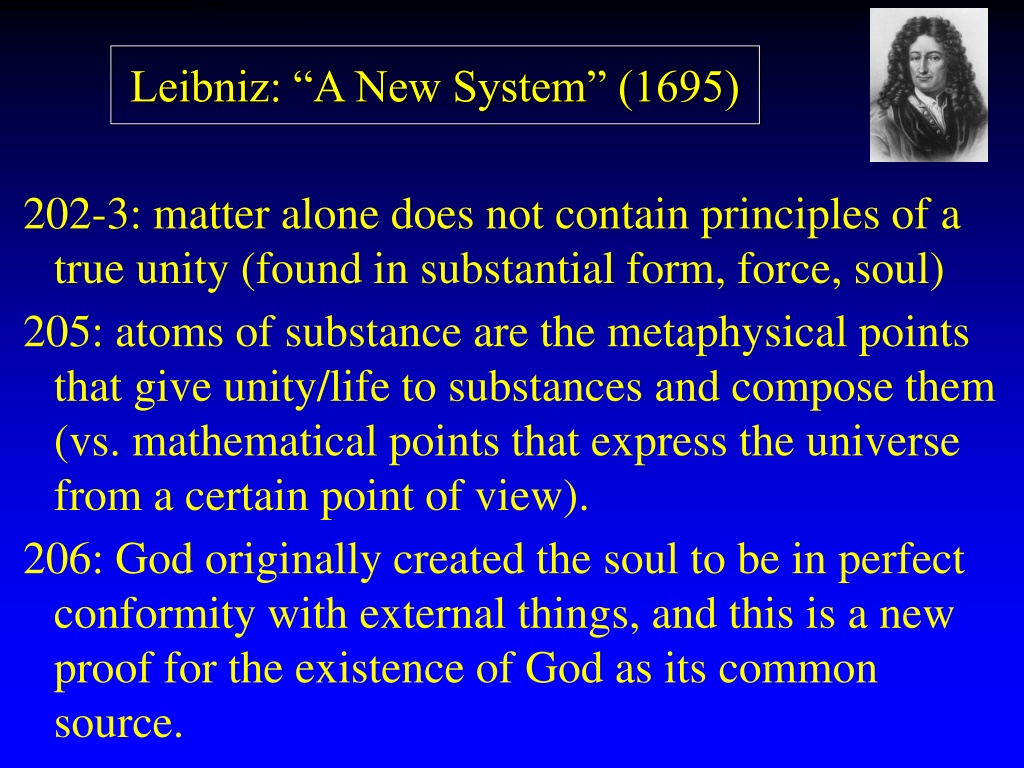

Leibniz: A New System (1695) 202-3: matter alone does not contain principles of a true unity (found in substantial form, force, soul) 205: atoms of substance are the metaphysical points that give unity/life to substances and compose them (vs. mathematical points that express the universe from a certain point of view). 206: God originally created the soul to be in perfect conformity with external things, and this is a new proof for the existence of God as its common source.

Leibniz: Preface to the New Essays concerning Human Understanding (1703-05) 208: we are created already knowing doctrines that are awakened in sense experience. But sense knowledge is only of particular truths, not of universal truths. 209: necessary truths (e.g. mathematics, logic, morality, metaphysics) depend on innate reasoning, not sense perception. Animals have no necessary propositions, nor are they capable of demonstrative knowledge. 210: ideas of being, unity, substance, duration, change, action, perception, pleasure are innate. Unlike Locke, Leibniz and the Cartesians think that a substance is always acting and a body is always moving.

Leibniz: Preface to New Essays 211: Through tiny perceptions, the present is filled with the future and laden with the past. There is a pre-established harmony between the soul and body and among all substances. 212: Nature makes no leaps: everything that happens gradually emerges or goes out of consciousness (law of continuity). 212: Two souls are different in virtue of their points of view of the universe. Their difference is always more than simply numerical. Every soul (or substance 216) is always joined to a body.

Leibniz: Preface to New Essays 214-15: for Locke, God can create material and immaterial substances without activities (e.g. thinking) but Leibniz denies this. 215: it is not natural for matter to sense or think, but (contra the Cartesians) animals do sense. That does not mean that matter can think (unless God were to make it so miraculously).

Leibniz: Letters to Clarke (1715-16) 226: principle of sufficient reason: nothing happens without a reason 227: contra Clarke, matter exists everywhere there is space: there is no void. (230: no extension is empty, for that would be an attribute without a subject.) 228: space (which consists of parts) is not something that belongs to God. It is merely relative, the order of coexistences (like time is the order of successions). 229: God cannot act without reason 230: the attraction of bodies is miraculous since it cannot be explained by the nature of bodies.

Leibniz: Letters to Clarke 230: Principles of sufficient reason and the identity of indiscernibles show how all things have to have a cause. 231: If space is an absolute reality, it will be greater than substances and not even God could modify or destroy it. Space and time are not absolute; they are only orders of things (also 233). 232: Space is simply the place of things, not the place of God s ideas. Because nature depends upon God, it is as perfect as it can be. 233: All things contain a world of all other things and are as perfect as they can be. The existence of the void would violate the necessity of sufficient reason.