Graph Theory: Friendship Theorem and Freshman's Dream

Explore the intriguing concepts of the Friendship Theorem and Freshman's Dream in graph theory along with examples and visual illustrations. Learn about common friends, relationships between vertices and edges, and what defines a graph in a concise yet comprehensive manner.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

The Friendship Theorem Dr. John S. Caughman Portland State University

Public Service Announcement Freshman s Dream (a+b)p=ap+bp mod p when a, b are integers and p is prime.

Freshmans Dream Generalizes! (a1+a2+ +an)p=a1p +a2p+ +anp mod p when a, b are integers and p is prime.

Freshmans Dream Generalizes * a1 A = * * 0 a2 * * 0 0 a3 * 0 0 0 a4 (a1+a2+ +an)p = a1p +a2p+ +anp tr(A) p = tr(Ap) (mod p)

Freshmans Dream Generalizes! * * A = * * * * * * * * * * * * * * tr(A) p = tr(Ap) (mod p) tr(A p)= tr((L+U)p) = tr(Lp +Up) = tr(Lp)+tr(Up)=0+tr(U)p = tr(A)p Note:tr(UL)=tr(LU) so cross terms combine , and coefficients =0 mod p.

The Theorem If every pair of people at a party has precisely one common friend, then there must be a person who is everybody's friend.

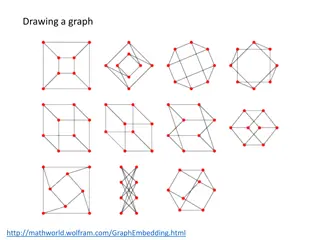

Cheap Example Nancy John Mark

Cheap Example of a Graph Nancy John Mark

What a Graph IS: Nancy John Mark

What a Graph IS: Nancy Vertices! John Mark

What a Graph IS: Nancy Edges! John Mark

What a Graph IS NOT: Nancy John Mark

What a Graph IS NOT: Loops! Nancy John Mark

What a Graph IS NOT: Loops! Nancy John Mark

What a Graph IS NOT: Nancy Directed edges! Mark John

What a Graph IS NOT: Nancy Directed edges! Mark John

What a Graph IS NOT: Nancy Multi-edges! John Mark

What a Graph IS NOT: Nancy Multi-edges! John Mark

Simple Graphs Nancy Finite Undirected No Loops No Multiple Edges John Mark

The Theorem, Restated Let G be a simple graph with n vertices. If every pair of vertices in G has precisely one common neighbor, then G has a vertex with n-1 neighbors.

The Theorem, Restated Generally attributed to Erd s (1966). Easily proved using linear algebra. Combinatorial proofs more elusive.

NOT A TYPICAL THRESHOLD RESULT

Pigeonhole Principle If more than n pigeons are placed into n or fewer holes, then at least one hole will contain more than one pigeon.

Some threshold results If a graph with n vertices has > n2/4 edges, then there must be a set of 3 mutual neighbors. If it has > n(n-2)/2 edges, then there must be a vertex with n-1 neighbors.

Extremal Graph Theory If this were an extremal problem, we would expect graphs with MORE edges than ours to also satisfy the same conclusion

1 2

1 2 3

1 4 2 3

Of the 15 pairs, 3 have four neighbors in common and 12 have two in common. So ALL pairs have at least one in common. But NO vertex has five neighbors!

Summary If every pair of vertices in a graph has at least one neighbor in common, it might not be possible to remove edges and produce a subgraph in which every pair has exactly one common neighbor.

Accolades for Friendship The Friendship Theorem is listed among Abad's 100 Greatest Theorems The proof is immortalized in Aigner and Ziegler's Proofs from THE BOOK.

How to prove it: STEP ONE: If x and y are not neighbors, they have the same # of neighbors. Why: Let Nx = set of neighbors of x Let Ny = set of neighbors of y

How to prove it: y x

How to prove it: y x Nx

How to prove it: y x Ny