Evolving Perspectives on Literature and Translation

Explore the intertwined relationship between national literature, comparative literature, and world literature, delving into the evolution of translation studies. Reflect on the shift from national literary histories to world histories of literature, highlighting the significance of world literature in today's globalized world.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

A World of Translation Theo D haen Lund 10 October 2019

Tangled relationship National Literature Comparative Literature World Literature Translation/Translation Studies

15 January 1827, first mention 31 January 1827: national literature has not much meaning nowadays: the epoch of world literature is at hand, and each must work to hasten its coming 21 brief passages on Weltliteratur Weltliteratur

At the same time The Rise of National Literary Histories as Repositories of National Memory seeing Literature as the genius of the nation and as reflecting a people s growth and development, as expressive of national character

The emphasis on national literatures as distinct and unique because expressive of national character also leads to a view of world literature as not one body, as presumably with Goethe, but as a cumulation of separate literatures alongside one another this gives rise to what will become a genre in itself: world histories of literature rather than histories of world literature

Such histories throughout the 19th and 20th centuries give most space to their own national literature, and then to European literature (selectively), and in fact little to the rest of the world

National standpoint of the observer English-speaking peoples

Neues Handbuch der Literaturwissenschaft (New Handbook of Literary Studies; 25 vols., 1972 2008) Istorija vsemirnoj literatury v devjati tomach (A History of World Literature in Nine Volumes; 8 vols., 1983 94) Verdens litteraturhistorie (The Literary History of the World; 7 vols., 1985 93)

commonly, about 80 per cent of the space is taken up by the treatment of literature in European languages (English, French, German, Spanish, Italian, et cetera), while 20 per cent is allotted to other literatures (literature in Chinese, Japanese, Indian languages, Arabic, African languages, and so on)

Closest English equivalent: multi-volume anthologies Norton Anthology of World Literature (1955 2010s) Longman Anthology of World Literature (2004 2010s) gradually more inclusive, though largely suffering same ills as multi-volume histories

Now What does translation have to do with all this?

- National literatures: n/a; until recently often discarded or overlooked - Comparative Literature: emphasizes study in the original - Histories of World literature/World Histories of Literature: theoretically dispensable but - Moretti s (2000) problem in Conjectures on World Literature (2000) - Anthologies: indispensable

Why Morettis problem? Since 1980s/1990s extension of both the canon of world literature and of the number of literatures of the world to be included in world histories of literature beyond anyone s powers of mastery of languages, so distant reading and collaborative work

But also: relying on translation

Albert Gurard; Preface to World Literature (1940) chapter one: Translation: the Indispensable Instrument

Tallies with the very beginnings of Weltliteratur: Goethe inspired by reading of Chinese novel in translation and by translations of his own work (Tasso) Birus (2000): Goethe regards the process of development of world literature as profoundly bound up with the medium of literary translation, over and above our striving for the widest possible direct knowledge of the various literatures, and over and above the lively interaction among Literatoren (that is poets, critics, university teachers, etc.)

Anthologies historically in translation - US undergraduates - responsibility of English Departments - US identity-building as European-descended - US in the world reflecting changes in US domestic demographics and geopolitical realities

This is where we enter the minefield of power relations in translation as explored by translation studies Bassnett 1993: the process of translating texts from one cultural system into another is not a neutral, innocent, transparent activity ... translation is instead a highly charged, transgressive activity

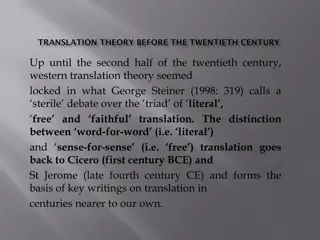

Particularly active on this score has been Lawrence Venuti, with numerous publications and his distinction between domesticating and foreignizing methods of translation

This distinction in fact is not new, though it has been most influential over the past two decades or so but it is already to be found, albeit with a different vocabulary, with Goethe, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940), and even Schleiermacher (1768-1834)

Venuti in Translation, Community, Utopia, the article that concludes his The Translation Studies Reader (2000), gives various examples of the domesticating tradition he sees at work in Anglo-American translation practices I just want to add an even more crass recent example Flemish author Annelies Verbeke meeting some US editor-scouts during a stay at a US writers colony

if we publish something European we obviously have to cut a lot , she said ... or I have to add a lot. Recently we published an Italian bestseller, by a famous movie director, one million copies sold in Italy, but what do you want, there were seven pieces missing, so I had to write those myself

Somebody asked: what do you mean that those pieces were missing ? Apparently the Italians liked it like that? The woman answered that this did not mean that the book was good enough for Americans.

Later another editor remarks to Verbeke that You should know that only one percent of one percent of what is published in Europe is good enough for America the message was clear to Verbeke: You people cannot write, but once in a while we are willing to try and improve such inferior work ....

The worst of it all, Verbeke adds, is that apparently the editors in question were in good faith, and genuinely convinced of helping and furthering the cause of those poor European

In essence, this is also what Gayatri Spivak has accused anthologies la Damrosch of: of domesticating the literatures of the world to turn into extensions of the US in the world rather than, as Damrosch put it in What Is World Literature (2003), a window opened unto the world - world literature in translation as an instrument of nation-building, nation-aggrandizement or nation- projection, even if probably unintentionally so

In truth, Goethe was not innocent of similar ambitions when he started exploring the possibilities of Weltliteratur, when he said that it was his conviction that a universal world literature is in process of formation in which we Germans are to play an honorable part

Specifically, as German literature at the time was not backed by a strong nation state as was the case with French and English literature, it had to seek for itself a mediating role in propagating world literature, especially because of what he saw as the German genius for translation

As Venuti notes, even before Goethe, Schleiermacher, in 1813, had argued that our language can thrive in all its freshness and completely develop its own power only by means of the most many-sided contacts with what is foreign thus seeing translation as a means of strengthening the German language as an agent for German cultural unification Kulturnation - against French dominance, cultural-linguistic and at the time of also political and military

Azucena Blanca, in Translation studies for a world community of literature, in Translation and World Literature (2019), ed. Susan Bassnett, makes a similar case for all those literatures Paulo de Medeiros, in Translation and cosmopolitanism, in the same volume, calls (semi)-peripheral, which is to say almost all literatures in the world except a very few, and in the present situation, where Auerbach s fear from his 1952 Philology and Weltliteratur may seem to be coming true, perhaps all except English-language literature.

Blanca calls for World literature as a pluriversal model of diverse historical world experiences, making it possible to sketch out the horizon of an aesthetics of equality. This equality has to be understood as an aesthetic of equality, that is to say, according to the normative and mimetic nature of the world, political equality is first an aesthetic potentiality of every literature as part of world literature. (p. 56)

This, in fact, sounds very much from the perspective of translation like the world literature Pheng Cheah propagates in What Is a World? On Postcolonial Literature as World Literature (2016), in which he stresses the normative dimension of postcolonial works as furthering the emancipative ambitions of those hitherto oppressed by European colonial powers, or the West in general, and as embodied in the literature emanating from them

This, then is a program for translation not a description of the actuality of the field; and perhaps somewhat akin to Emily Apter s (2008) call for a translational humanities responsive to fluctuations in geopolitics

At the same time, such calls implicitly also always already embody calls for a stronger affirmation of existing nation-formations, as would seem to be the case with De Medeiros, or different identity- formations, be they different nation-formations (including regional ones), as would seem to be the case with Cheah and Blanca, or transnational categories of migrants, colonized, or political refugees whose histories Homi Bhabha(1994) suggested as now being the terrains of world literature

Translation, and translational practices with respect to world literature, then, can be invoked and applied in many different ways, but rarely if ever without ulterior motive, almost invariably related to some form of nation or identity-formation

Venuti, in the article of his mentioned earlier, puts this most succinctly when he claims that (p. 180), translation can support the formation of national identities through both the selection of foreign texts and the development of discursive strategies to translate them

Obvious instances are when works from the canon of world literature, even avant-la- lettre, are selected because they present a case analogous to that of the translating culture and then bent to that culture s national conventions

Virgils Aeneid, the most prestigious instance of the most prestigious genre, the epic, offers the example of an actual (mythical) nation- formation moment, and carries the prestige of its Roman legacy, which warrants its selection for translation in most at least Western European - literatures at some point, but is then nationalized via the meter adopted

and then imitated in such national epics as Ronsard s Franciade (1572), using the twelve-syllable alexandrine that eventually came to stand in as the French substitute for the classic dactylic hexameter and which is also used by Voltaire for his Henriade (1728)

With the advent of Humanism and the rediscovery of Greek literature and particularly Homer s Iliad and Odyssey, the same thing happens, with George Chapman using a iambic pentameter for his Iliad and a iambic heptameter for his Odyssey (both 1616), and Alexander Pope for his 1720 versions also using a iambic pentameter, while both use rhyming couplets.

Or take translations of Ariostos Orlando furioso (1532) or Tasso s Gerusalemme liberata (1581), the most prestigious epic romances of the sixteenth century, written in hendecasyllables, typical for Italian poetry, being turned into decasyllable iambic pentameter in English, and in alexandrines in Diederich von dem Werder s 1626 Gottfried von Bulljon, Oder das erl ste Jerusalem

The reverse can also happen, as with the nineteenth-century Dutch translations of Byron here Venuti s claim comes into play that (p. 186) cultural differences ... can intensify a reader s sense of belonging to a national collective and may even elicit an unconscious desire for a unified nation distinct from the foreign nation that the text is meant to represent

Byrons verse was perceived to be so distant from what the Dutch saw as their national character and from the political realities of their nation in the second quarter of the nineteenth century that translations of his poetry only served to underline that distance and this was emphasized again by an imitation of Byron s Don Juan by De Genestet

The final stanzas of P .A. De Gnestets Fantasio (1848) read: I spoke to every maiden, filling her head with novels and poetry: dearest child, watch out for the Don Juans! Keep shut your eyes and your ear and your heart and your mouth and your window! Don't ever get involved with eloping or dangerous rendez-vous, and give yourself the time to find out about those gentlemen that deem themselves irresistible: otherwise you might be sorry .

You, young man, straighten out your brains, be ardent in your love, if you so wish, but be steady, and if ever you fall in love, draw up a domestic plan, stay calm and serious, behave like a man: my advice to you is to first take a little walk around the block, and never to decide upon these matters in a hurry.

We may see something similar with the nineteenth-century discussion in England of Homer and the dactylic hexameter as instanced in Metrical Translation: Nineteenth-Century Homers and the Hexameter Mania, an article by Yopie Prins in Nation, Language, and the Ethics of Translation, eds. Sandra Bermann and Michael Wood (2005).

Whereas Homer in earlier translations, as I briefly indicated, was nationalized via the meter employed, Matthew Arnold tried to reverse this by enlisting Homer s dactylic hexameter in the service of the formation of a national literary culture unifying and stabilizing what to many had become a chaotic empire.

As Prins (p. 229) puts it: with the rise of the British empire, as England was struggling to accommodate foreignness both within and beyond its national borders, the consolidation of a common language out of heterogeneous elements seemed especially urgent. For Arnold, the hexameter exemplified the civilizing measures of meter and a measured response to modern times. (Prins p. 250)