Economics Lecture Series on Scarcity, Work, and Choice

Delve into the concepts of trade-offs, opportunity costs, and optimal decision-making under scarcity conditions. Explore the effects of relative price changes, technological advancements, and the determinants of hours worked in different economies. Uncover significant questions regarding the evolution of working hours and the impact of regulations on labor practices across countries.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

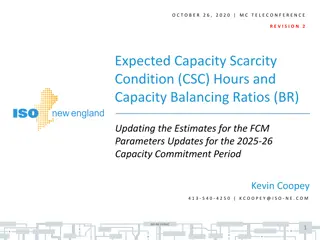

EC107 Economics 1 Scarcity, Work and Choice This series of mini-lectures on Scarcity, Work and Choice follows closely CORE The Economy: Unit 3 vid Intended Learning Outcomes You will have a clear understanding and the capability of explaining: 1. The concepts of trade-offs, opportunity costs and the economic analysis of optimal decision-making under conditions of scarcity 2. The concepts of the Income and Substitution Effects when relative price changes 3. 4. The determinants of hours worked by workers in an economy The impact of technological change on hours worked. Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Scarcity, Work and Choice vid The analysis we will develop in this Unit will enable us to address some hugely important questions, such as: 1. Why has the average number of hours people work each year fallen so much in the last hundred years in developed economies? 2. Why do the number of hours worked vary so much across countries? 3. What is the link between technological change, living standards and hours of work? (Was Keynes right in his predictions about the evolution of working hours into the future?) Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

In different countries at different times, the hours people have worked have varied enormously and rules and regulations concerning hours of work have similarly varied. England: The Factory Act of 1833 (Textiles) Maximum hours per day Children aged <13: Youths aged <18: vid 8 hours 12 hours Mines and Collieries Act 1842: forbade women and girls of any age to work underground and introduced a minimum age of ten years of age for boys employed in underground work. Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

vid The ILO continues to campaign against child labour around the World Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

Annual hours worked and GDP per capita over time and across countries vid Consider the case of the US Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

Annual hours worked and GDP per capita over time and across countries vid Consider the case of the Netherlands Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

Average annual hours of free time and GDP per capita across countries (2013) vid Describe the cross-country relationship between GDP per capita and Free Time per worker. What might explain this relationship? Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Scarcity, Work and Choice: Unit 3 vid Part 2: Production, Preferences, Choices Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Grades and study hours: the production function Production functions show how inputs (e.g. labour) translate into outputs (e.g. goods and services), holding other factors constant (e.g. capital). vid The diagram shows an application in which the input is study hours and the output is the final exam mark. The next slide looks at the effects of changes in inputs Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 What can we learn from production functions? vid Suppose initially the student is studying for 4 hours per day. What will be their final mark? If they studied for one more hour, by how much would their grade change? What is the marginal product of an hour of study time? Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 What can we learn from production functions? Slope of Production Function = Marginal product of study time = [ in mark]/[ in study time] vid For very small changes in study time, the marginal product of study time is given by the slope of the production function. 1 Let s check we understand why this is Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 What can we learn from production functions? Slope of Production Function = Marginal product of study time = [ in mark]/[ in study time] vid b 7 marks a 4 5 Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 What can we learn from production functions? Slope of Production Function = Marginal product of study time = [ in mark]/[ in study time] vid b 7 marks a 4 5 Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 What can we learn from production functions? Slope of Production Function = Marginal product of study time = [ in mark]/[ in study time] vid So, for very small changes in study time, the marginal product of study time is given by the slope of the production function. a 4 Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 What can we learn from production functions? Slope of Production Function = Marginal product of study time = [ in mark]/[ in study time] vid Suppose initially the student is studying for 10 hours per day. 1 What will be their final mark? What is their average product of an hour of study time when they study for 10 hours? Discuss And the marginal product? And the relative size of the two? Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 What can we learn from production functions? Slope of Production Function = Marginal product of study time = [ in mark]/[ in study time] vid We conclude that while the Marginal Product is given by the slope of the tangent of the production function 1 the Average Product of study time is given by the slope of the ray from the origin to the production function. 2 Slope of ray from the origin to the Production Function = Average product of study time = Mark/Study hours Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 What can we learn from production functions? Slope of Production Function = Marginal product of study time = [ in mark]/[ in study time] vid So for any given amount of study time, which is greater: the marginal product or the average product? As study time increases, what happens to the marginal product of study time? DMPL As study time increases, what happens to the average product of study time? DAPL Slope of ray from the origin to the Production Function = Average product of study time = Mark/Study hours Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 We can derive (i.e., plot) the marginal and average returns from the production function vid 20 15 10 5 0 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 Marginal return of study hour Average return of study hour Diminishing marginal product: at the margin, studying becomes less productive, the more you study. Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 An important aim of Unit 3: Scarcity, Work and Choice is to understand how technological change, through raising labour productivity, might affect individuals choices of free time and working hours. vid The production function shows how the individual s choice between hours of study/work and free time impacts on grades. The production function acts as a constraint: you can have more free time, but you have to give up higher grades. In order to understand the individual s choice or decisions concerning how they allocate their time, we need to combine this notion of a constraint with an understanding of the individual s preferences between studying/working and free time. Choices depend on both preferences and constraints. This will be the subject of the next mini-lecture. Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Scarcity, Work and Choice: Unit 3 vid Part 2: Trade-offs, Marginal Rate of Substitution, Marginal Rate of Transformation Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

In Unit 3 Part 2, we derived the MPL and the APL from the production EC107 Economics 1 function. We did so for the case of Study Hours (input) and Exam Marks (output). More generally: vid MPL X APL X=X(L) APL MPL L L Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 For self-study: What would the APL and MPL look like for this alternative case of a production function? vid MPL X APL X=X(L) ? L L Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

What would the APL and MPL EC107 Economics 1 look like for this alternative case of a production function? vid MPL X X=X(L) APL ? L L Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

What would the APL and MPL EC107 Economics 1 look like for this alternative case of a production function? vid MPL X X=X(L) APL ? L L Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

Most generally, what would the APL and MPL EC107 Economics 1 look like for this alternative case of a production function? vid X=X(L) MPL X APL ? L L Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 As we discussed in Unit 3 Part 2: vid Choices depend on both preferences and constraints. The production function represents a constraint. We now focus on preferences, before bringing the two together in our model of choice/decision-making. Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid We represent preferences in a diagram by Indifference Curves, which show all combinations of goods that give the same utility (satisfaction). Let X and Y be two goods you enjoy. Suppose I offer you the combination X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid I am offering you (think of it as a gift) the combination . This bundle or basket contains a relatively large amount of Y and relatively little of X. I then invite you to say whether you would prefer the bundle or various alternative bundles X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Suppose I offer you as an alternative to . You might respond by saying: The additional amount of X does not compensate me for the amount of Y that I would be giving up if I were to take . Hence, I prefer to stick with , thank you. X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid I then reply by offering you the bundle , which has the same amount of Y as does , but has more X than . How might you respond to this? X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Suppose you now respond with: Thank you: that s better than the bundle . In fact, compared to the initial offering of , the additional X is now exactly enough to compensate me for the reduction in the amount of Y. Yes, I am exactly indifferent between the two bundles and . They give exactly the same amount of satisfaction. X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid As you are now exactly indifferent between the two bundles and , we say that they are both points on a locus of points representing equal levels of satisfaction. We call this locus of points an Indifference Curve. IC1 From the positions of and in the diagram, it s clear that the Indifference Curve (IC1) which passes through and must be downward-sloping. X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Suppose I now offered you bundle , which has the same amount of X as does , but has more Y. Which would you prefer: or ? IC1 X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Assuming, as we are, that more of any good yields greater satisfaction (it s why IC1 slopes downwards), you would respond by telling me you prefer over . IC2 Assuming that there is an IC passing through each and every possible bundle, this means that will lie on an IC that lies above IC1. IC1 X Call it IC2 Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid IC3 IC2 So we can show whole families of Indifference Curves representing preferences of individuals. IC1 IC0 X But are they necessary linear? Let s think about other possible shapes Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Self-Study Questions IC1 What would it imply about an individual s preferences over X and Y if their Indifference Curves were all horizontal? X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid IC1 Self-Study Questions What would it imply about an individual s preferences over X and Y if their Indifference Curves were all vertical? X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Self-Study Questions IC1 What would it imply about an individual s preferences over X and Y if their Indifference Curves were all downward-sloping at an angle of 45 degrees? 45o X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Self-Study Questions What would it imply about an individual s preferences over X and Y if their Indifference Curves were all L-shaped with corners along a ray from the origin, with the ray having an angle of 45 degrees? IC1 45o X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Self-Study Questions What would it imply about an individual s preferences over X and Y if their Indifference Curves were all downward-sloping (though at an angle other than 45 degrees)? IC1 X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid See Slide 43 IC1 X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Self-Study Questions What would it imply about an individual s preferences over X and Y if their Indifference Curves were downward-sloping up to a certain level of X and thereafter became upward-sloping? IC1 X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Definition The marginal rate of substitution (MRS) is the slope of the indifference curve, and represents the tradeoffs that an individual is prepared to make between the two goods: i.e., how much Y they will give up to have an extra unit of X. X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Let s interpret the MRS in the diagram The horizontal arrow shows an additional amount of X you are being offered. X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Let s interpret the MRS in the diagram The horizontal arrow shows an additional amount of X that you are being offered. The vertical arrow shows just how much Y you are prepared to forgo (give up) in order to have the additional X and be just as satisfied as initially at . X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid Therefore, the slope of a straight line linking and (see diagram) shows us how much Y you are prepared to give up (dY) to have the additional X (dX). The slope of this line is given by: dY dX dY/dX X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid As the difference between and becomes progressively smaller, the slope of the line between the two points approximates to the slope of the curve itself at any point. Hence, it follows that dY dX X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid The marginal rate of substitution (MRS) is the slope of the indifference curve, and represents the tradeoffs that an individual is prepared to make between the two goods: i.e., how much Y they are willing to give up to have an extra unit of X. dY dX If the indifference curve becomes flatter to the right this indicates that the MRS is diminishing the individual is prepared to trade-off only a small reduction in Y in order to have more X when they anyway have relatively little Y and a lot of X. X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Choices depend on preferences and constraints Y vid In the next mini-lecture, we return to the particular application in which we are considering a student s choice of study hours. In the previous mini-lecture, we considered the production function as the constraint they faced. We are now in a position to analyse optimizing choices through considering the interplay of the student s production function (their constraint) and their indifference curves (their preferences). X Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick

EC107 Economics 1 Scarcity, Work and Choice: Unit 3 vid Part 4: Production Functions and Indifference Curves combined Robin Naylor, Department of Economics, Warwick