Ecology: Interactions and Environments in Biology

Ecology is the study of interactions between living organisms and their environment. It involves levels of research such as animal ecology, plant ecology, and more, while also exploring the biosphere's impact, biogeography, species distribution patterns, and energy sources like sunlight. Ocean upwelling plays a crucial role in nutrient recycling in marine ecosystems.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Ecology of Living Things Biology for Majors

What is Ecology Ecology is the study of the interactions of living organisms with their environment.

Levels of Ecological Research

Ecology can be classified based on: the primary kinds of organism under study (e.g. animal ecology, plant ecology, insect ecology) the biomes principally studied (e.g. forest ecology, grassland ecology, desert ecology, benthic ecology, marine ecology, urban ecology) the geographic or climatic area (e.g. arctic ecology, tropical ecology) the spatial scale under consideration (e.g. macroecology, landscape ecology) the philosophical approach (e.g. systems ecology which adopts a holistic approach) the methods used (e.g. molecular ecology)

The Biosphere The biosphere is all of the parts of Earth inhabited by life. The biosphere extends into the atmosphere and into the depths of the oceans. Many abiotic (non- living) forces influence where life can exist and the types of organisms found in different parts of the biosphere.

Biogeography Biogeography is the study of the geographic distribution of living things and the abiotic factors (such as temperature or rainfall) that affect their distribution.

Species Distribution Ecologists who study biogeography examine patterns of species distribution: An endemic species is one which is naturally found only in a specific geographic area that is usually restricted in size (like the Australian mammals below) Generalists can live in a wide variety of geographic areas.

Energy Sources Energy from the sun is captured by green plants, algae, cyanobacteria, and photosynthetic protists. These organisms convert solar energy into the chemical energy needed by all living things. Light availability can be an important force directly affecting the evolution of adaptations in photosynthesizers, like the plant below.

Ocean Upwelling Ocean upwelling is an important process that recycles nutrients and energy in the ocean.

Spring and Fall Turnover The spring and fall turnovers in freshwater lakes that act to move the nutrients and oxygen at the bottom of deep lakes to the top.

Temperature Temperature limits the distribution of living things because few living things can survive at temperatures below 0 C or above 45 C. Animals faced with temperature fluctuations may respond with adaptations, such as migration or hibernation, in order to survive.

Abiotic Factors that Influence Plant Growth Temperature, moisture, soil nutrients, and light are important influences on plant production (primary productivity) and the amount of organic matter available as food (net primary productivity). Net primary productivity is an estimation of all of the organic matter available as food; it is calculated as the total amount of carbon fixed per year minus the amount that is oxidized during cellular respiration. In terrestrial environments, net primary productivity is estimated by measuring the aboveground biomass per unit area, which is the total mass of living plants, excluding roots.

Other Abiotic Factors Water Oxygen Wind Fire

Biomes Each of the world s major biomes is distinguished by characteristic temperatures and amounts of precipitation.

Tropical Wet Forests Tropical wet forests have high net primary productivity because the annual temperatures and precipitation values in these areas are ideal for plant growth. Therefore, the extensive biomass present in the tropical wet forest leads to plant communities with very high species diversities.

Savannas Savannas are grasslands with scattered trees. Savannas are hot, tropical areas with temperatures averaging from 24 C to 29 C and an annual rainfall of 10 40 cm (3.9 15.7 in). Savannas have an extensive dry season, so forest trees do not grow as well. Plants evolved well-developed root systems that allow them to quickly re-sprout after a fire.

Subtropical Deserts Low and unpredictable precipitation limits the vegetation and animal diversity of this biome. Very dry deserts lack perennial vegetation that lives from one year to the next; instead, many plants grow quickly and reproduce when rainfall does occur, then they die. Other plants are adapted to conserve water, with deep roots, reduced foliage, water-storing stems, or seeds that can be dormant between rains. Desert animals may be nocturnal or burrow.

Chaparral The chaparral, or scrub forest, has annual rainfall that ranges from 65 cm to 75 cm, and the majority of the rain falls in the winter. Summers are very dry and many chaparral plants are dormant during the summertime. The chaparral vegetation is dominated by shrubs and is adapted to periodic fires. The ashes left behind fertilize the soil and promote plant regrowth.

Temperate Grasslands Temperate grasslands have pronounced annual fluctuations in temperature with hot summers and cold winters. The annual temperature variation produces specific growing seasons for plants. The vegetation is very dense and the soils are fertile because the subsurface of the soil is packed with the roots and rhizomes (underground stems) of these grasses. Often, the restoration or management of temperate grasslands requires the use of controlled burns to suppress the growth of trees and maintain the grasses.

Temperate Forests The temperature range 30 C and 30 C give temperate forests a growing seasons during the spring, summer, and early fall. Precipitation is relatively constant and ranges 75 cm-150 cm. Deciduous trees are the dominant plant in this biome. Since they lose their leaves in the winter, the net primary productivity of temperate forests is less than that of tropical wet forests. The soils of the temperate forests are rich in inorganic and organic nutrients from decaying leaf litter.

Boreal Forest This biome has cold, dry winters and short, cool, wet summers. The long and cold winters in the boreal forest have led to the predominance of cold-tolerant evergreens. The net primary productivity of boreal forests is lower than that of temperate forests and tropical wet forests. They host less diversity.

Arctic Tundra Plants in the arctic tundra have a very short growing season of approximately 10 12 weeks, but with almost 24 hours of sunlight, growth is rapid. This biome is cold and dry. Plants in the Arctic tundra are generally low to the ground. There is little species diversity, low net primary productivity, and low aboveground biomass. The soils of the Arctic tundra may remain in a perennially frozen state referred to as permafrost.

Characteristics of Aquatic Biomes The ocean is divided into different zones based on water depth and distance from the shoreline. Available light and oxygen affect what can live in each.

Coral Reefs Coral reefs are ocean ridges formed by marine invertebrates living in warm shallow waters within the photic zone of the ocean. It is estimated that more than 4,000 fish species inhabit coral reefs.

Lakes and Ponds Light can penetrate within the photic zone of the lake or pond. Phytoplankton (algae and cyanobacteria) are found here and carry out photosynthesis, providing the base of the food web of lakes and ponds. Zooplankton, such as rotifers and small crustaceans, consume these phytoplankton. At the bottom of lakes and ponds, bacteria in the aphotic zone break down dead organisms that sink to the bottom. Nitrogen and Phosphorous in sewage and storm water runoff pose significant environmental challenges.

Rivers and Streams Rivers and streams are continuously moving bodies of water that carry large amounts of water from the source, or headwater, to a lake or ocean. Abiotic features of rivers and streams vary along the length of the river or stream. Near the headwaters, water is fast-moving and clear. Closer to the lake or ocean it is murkier and slower moving. Different organism are adapted to these parts of the river.

Wetlands Wetlands are environments where the soil is either permanently or periodically saturated with water. Wetlands are different from lakes because wetlands are shallow bodies of water whereas lakes vary in depth. Emergent vegetation consists of wetland plants that are rooted in the soil but have portions of leaves, stems, and flowers extending above the water s surface. There are several types of wetlands including marshes, swamps, bogs, mudflats, and salt marshes (figure above). The three shared characteristics among these types what makes them wetlands are their hydrology, hydrophytic vegetation, and hydric soils.

Estuaries Estuaries are biomes that occur where a source of fresh water, such as a river, meets the ocean. Therefore, both fresh water and salt water are found in the same vicinity; mixing results in a diluted (brackish) saltwater. Estuaries form protected areas where many of the young offspring of crustaceans, mollusks, and fish begin their lives. Salinity is a very important factor that influences the organisms and the adaptations of the organisms found in estuaries.

Population Demography Populations are dynamic entities. Populations consist all of the species living within a specific area, and populations fluctuate based on a number of factors: seasonal and yearly changes in the environment, natural disasters such as forest fires and volcanic eruptions, and competition for resources between and within species. The statistical study of population dynamics, demography, uses a series of mathematical tools to investigate how populations respond to changes in their biotic and abiotic environments.

Population Size and Density Within a particular habitat, a population can be characterized by its population size (N), the total number of individuals, and its population density, the number of individuals within a specific area or volume. Population size and density are the two main characteristics used to describe and understand populations. For example, populations with more individuals may be more stable than smaller populations based on their genetic variability, and thus their potential to adapt to the environment.

Inverse Relationship between Population Density and Body size

Population Research Methods Scientists usually study populations by sampling a representative portion of each habitat and using this data to make inferences about the habitat as a whole.

Quadrat Sampling For immobile organisms such as plants, or for very small and slow-moving organisms, a quadrat may be used. After setting the quadrats (below), researchers then count the number of individuals that lie within their boundaries. Multiple quadrat samples are performed throughout the habitat at several random locations.

Mark and Recapture For mobile organisms a technique called mark and recapture is often used.

Mark and Recapture Methodology This method involves marking a sample of captured animals in some way, and then releasing them back into the environment to allow them to mix with the rest of the population; later, a new sample is collected, including some individuals that are marked (recaptures) and some individuals that are unmarked. Using the ratio of marked and unmarked individuals, scientists determine how many individuals are in the sample. ?????? ?????? ????? ???? ????? ?????? ?? ?????? ???? ?????? ?????? ?????? ???? = ?

Species Distribution (continued) Territorial birds such as penguins tend to have uniform distribution. Plants such as dandelions with wind-dispersed seeds tend to be randomly distributed. Animals such as elephants that travel in groups exhibit clumped distribution.

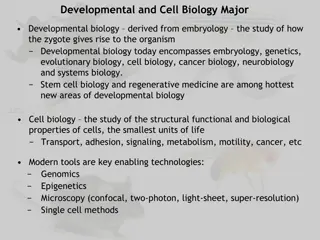

Demography Demography is the statistical study of population changes over time: birth rates, death rates, and life expectancies. Life tables provide important information about the life history of an organism. Life tables divide the population into age groups and often sexes, and show how long a member of that group is likely to live. Life tables may include the probability of individuals dying before their next birthday (i.e., their mortality rate), the percentage of surviving individuals dying at a particular age interval, and their life expectancy at each interval.

Survivorship Curve Survivorship curve, which is a graph of the number of individuals surviving at each age interval plotted versus time (usually with data compiled from a life table). These curves allow us to compare the life histories of different populations.

Life Histories and Natural Selection All species have evolved a pattern of living, called a life history strategy, in which they partition energy for growth, maintenance, and reproduction. These patterns evolve through natural selection; they allow species to adapt to their environment to obtain the resources they need to successfully reproduce. There is an inverse relationship between fecundity and parental care. A species may reproduce early in life to ensure surviving to a reproductive age or reproduce later in life to become larger and healthier and better able to give parental care. A species may reproduce once (semelparity) or many times (iteroparity) in its life.

Semelparity and Iteroparity A species may reproduce once (semelparity) or many times (iteroparity) in its life. The (a) Chinook salmon mates once and dies. The (b) pronghorn antelope mates during specific times of the year during its reproductive life. Primates, such as humans and (c) chimpanzees, may mate on any day, independent of ovulation.

Limits to Population Growth Populations with unlimited resources grow exponentially, with an accelerating growth rate. When resources become limiting, populations follow a logistic growth curve. The population of a species will level off at the carrying capacity of its environment.

Population Dynamics The logistic model of population growth is a simplification of real-world population dynamics. Implicit in the model is that the carrying capacity of the environment does not change, which is not the case. Carrying capacity can vary with season and from year to year. Additionally, populations do not usually exist in isolation. They engage in interspecific competition: that is, they share the environment with other species, competing with them for the same resources.

Regulation Nature regulates population growth in a variety of ways. These are grouped into density-dependent factors, in which the density of the population at a given time affects growth rate and mortality, and density-independent factors, which influence mortality in a population regardless of population density.

Density Dependent Factors Most density-dependent factors are biological in nature (biotic), and include predation, inter- and intraspecific competition, accumulation of waste, and diseases such as those caused by parasites. Usually, the denser a population is, the greater its mortality rate. For example, during intra- and interspecific competition, the reproductive rates of the individuals will usually be lower, reducing their population s rate of growth. In addition, low prey density increases the mortality of its predator because it has more difficulty locating its food source.

Density-Independent Regulation Many factors, typically physical or chemical in nature (abiotic), influence the mortality of a population regardless of its density, including weather, natural disasters, and pollution. In real-life situations, population regulation is very complicated and density- dependent and independent factors can interact. A dense population that is reduced in a density-independent manner by some environmental factor(s) will be able to recover differently than a sparse population.

r-selected Species This strategy is often employed in unpredictable or changing environments.

K-selected Species K-selected species are species selected by stable, predictable environments. Populations of K-selected species tend to exist close to their carrying capacity (hence the term K-selected) where intraspecific competition is high.

Characteristics of K-selected and r-selected species Characteristics of K-selected species Characteristics of r-selected species Mature late Mature early Greater longevity Lower longevity Increased parental care Decreased parental care Increased competition Decreased competition Fewer offspring More offspring Larger offspring Smaller offspring