Comedy Evolution in Restoration Drama

Explore the evolution of comedy in Restoration drama, from the types of comedy to the major playwrights and their contributions. Learn about the dramatic and theatrical themes, conventions, and trends of the period 1660-1709, including the shift towards humane intrigue comedy and the influence of Spanish and French comedic styles on English playwrights.

Uploaded on Oct 02, 2024 | 1 Views

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

EN352: The Busy Body (1709) by Susannah Centlivre Dr Teresa Grant, February 2019

Learning Outcomes for EN352 Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the set plays in their political, religious and social contexts Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the major dramatic trends of the period 1660-1709 Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of Restoration literary and dramatic criticism in theory and practice

Exam Rubric Comment on the following extract in the context of Restoration drama. Do NOT write a line-by-line commentary but use it to explore the dramatic and theatrical themes and conventions of the Restoration stage, with detailed reference to the play from which it comes and AT LEAST one other play.

Types of Comedy after 1685 1. Humane intrigue comedy 2. Moral comedy, stressing repentance, reform and forgiveness 3. Farces designed as afterpieces Basically, in its outlook and value-system, humane comedy is soft and hence belongs to the new comedy camp. The old hard comedy simply withers away, while some of its plots and devices are subsumed into a new tradition. (Hume, 484)

Ben Jonson The Alchemist The Devil is an Ass Volpone

Types of Comedy Comedy of folly Comedy of intrigue Comedy of manners Comedy of humours Satirical comedy Farce

Comedy of intrigue A form of comedy which depends on an intricate plot full of surprises and tends to subordinate character to plot. This distinguishes it from comedy of manners (q.v.), though the latter may also have complex plots. The form originated in Spain and was largely the work of a group of four famous dramatists: Lope de Vega (1562 1635), Tirso de Molina (1571 1648), Alarc n (1581 1639) and Moreto (1618 69). It has not appealed much to English dramatists, but Mrs Aphra Behn made some distinguished contributions: The Rover (1677 81) and The City Heiress (1682). In France, Beaumarchais s Le Barbier de S ville (1775) deserves special mention.

Comedy of manners This genre has for its main subjects and themes the behaviour and deportment of men and women living under specific social codes. It tends to be preoccupied with the codes of the middle and upper classes and is often marked by elegance, wit and sophistication. In England Restoration comedy (q.v.) provides the outstanding instances. But Shakespeare s comedies Love s Labour s Lost (c. 1595) and Much Ado About Nothing (c. 1598 9) are also comedies of manners.

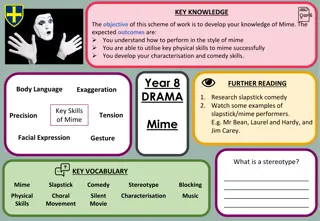

Comedy of humours A form of drama which became fashionable at the very end of the 16th c. and early in the 17th. So called because it presented humorous characters whose actions (in terms of the medieval and Renaissance theory of humours (q.v.)) were ruled by a particular passion, trait, disposition or humour. Basically this was a physiological interpretation of character and personality. Though there were ample precedents for this in allegory (q.v.), Tudor Morality Plays (q.v.), and Interludes (q.v.), Ben Jonson appears to have been the first person to have elaborated the idea on any scale. His two outstanding works in this kind of comedy are Every Man in His Humour (1598) and Every Man Out of His Humour (1599); plus minor works like The Magnetic Lady: or Humours Reconciled (1632). Following the practice of the Moralities and Interludes, Jonson named dramatis personae aptronymically: Kitely, Dame Kitely, Knowell, Brainworm and Justice Clement (in Every Man in His Humour); Fastidious Brisk, Fungoso, Sordido, and Puntarvolo the vainglorious knight, and so forth (in Every Man Out of His Humour). The indication of character in this fashion became a common practice and continued to be much favoured by dramatists and novelists in the 18th and 19th c.

Satirical comedy A form of comedy (q.v.), usually dramatic, whose purpose is to expose, censure and ridicule the follies, vices and shortcomings of society, and of individuals who represent that society. It is often closely akin to burlesque, farce and comedy of manners (qq.v.). Some of the best and earliest examples of satirical comedy are to be found in the plays of Aristophanes, especially his Acharnians, Knights, Clouds, Wasps, Birds, Frogs and Lysistrata. In English literature classic examples of the genre are Ben Jonson s Volpone (1606) and The Alchemist (1610); Sheridan s The School for Scandal (1777); Shaw s The Doctor s Dilemma (1906).

Satire (L satira, later form of satura, medley ) It may be a cooking term in origin or, as Juvenal called it, ollapodrida, mish-mash , farrago . According to Johnson, Swift and Pope, the satirist is a kind of self-appointed guardian of standards, and ideals; of moral as well as aesthetic values. He is a man (women satirists have been very rare) who takes it upon himself to correct and ridicule the follies and vices of society and thus to bring contempt and derision upon aberrations from a desirable and civilized norm. The history of satire begins with the early Greek and Roman literature. The great satirist of Greece was Aristophanes (c. 448 c. 380 bc), who used ridicule and abuse to great effect in several plays. In Rome, Horace wrote tolerant, urbane and amused satire of the human scene, while Juvenal s satires were bitter and misanthropic.

Farce (L farcire, to stuff ) As applied to drama the term derives from the OF farce, stuffing . Farce is a kind of low comedy, and its basic elements are exaggerated physical action (often repeated); exaggeration of character and farce situation; absurd situations and improbable events (even impossible ones and therefore fantastic); and surprises in the form of unexpected appearances and disclosures. In farce, character and dialogue are nearly always subservient to plot and situation. The plot is usually complex and events succeed one another with almost bewildering rapidity.

Marplot Sir Martin Mar-all (1667) by John Dryden: it is the most entire piece of mirth, a complete farce from one end to the other, that certainly was ever writ. I never laughed so in all my life. I laughed until my head ached all the evening and night with the laughing. Pepys Diary (1667). A version of Willmore? What are the differences? Why does Marplot keep getting beaten?

The Busy Body Plot and humours make the substance of the play: there are no serious attitudes or issues beneath the surface. There is no toughness in Centlivre s play, no strong feeling, no anger, no willingness to shock, offend or disturb. (Hume, 484)

Quotations were from J. A. Cuddon, A Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory (5th edition; Wiley Online Library, 2012). R. D. Hume, The Development of English Drama in the Later Seventeenth Century (Oxford, 1976).