Building Confidence in Public Speaking: Overcoming Anxiety and Developing Skills

Public speaking anxiety can hinder self-expression and success. Learn how to identify and address different forms of PSA, such as trait anxiety and state anxiety. Discover techniques to build confidence, manage apprehension, and enhance your public speaking skills effectively.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Chapter 2 Building Confidence

Learning Objectives In this chapter, you will learn how to build your own public speaking confidence by ? identifying and dealing with your own brand of public speaking anxiety ? applying cognitive restructuring (CR) techniques to create a more positive frame of reference. ? learning how to create a personal preparation routine to minimize your apprehension and become conversant in your topic.

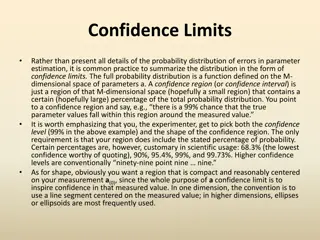

What Is Communication Apprehension? Public speaking anxiety (PSA) is a situation specific social anxiety arising from the real or anticipated enactment of an oral presentation (Bodie 72). Approximately a quarter of all people report having PSA. PSA can prevent you from taking risks to share your ideas, to speak about your work, and to present your solutions to problems that affect many people (Drevitch). Even mild PSA can affect your self-esteem (Adler, 1980), how you are perceived by others (Dwyer & Cruz, 1998), as well as success in school and in landing job interviews (Daly & Leth, 1976).

Dealing with Communication Apprehension Effective public speaking is not simply about learning what to say, but about developing the confidence to say it. To overcome this fear, you must first determine what causes your own unique brand of PSA.

Forms of PSA The fear of public speaking varies from person to person and is rooted in different life experiences. The three primary forms of PSA are Trait-anxiety ? State-anxiety ? Scrutiny fear ?

Trait Anxiety Trait anxiety is aligned with, or a manifestation of, an individual s personality. Example: People who would describe themselves as shy often seek to avoid interaction with others because they are uncertain of how they will be perceived. Eventually this avoidance becomes a pattern of behavior. Those with trait-anxiety are likely to view any chance to express themselves publicly with skepticism and hesitation.

State Anxiety State anxiety is the result of a previous adverse situation. Example: People with state-anxiety might have had a previous embarrassing experience with speaking in public such forgetting a line while performing in a school play or becoming tongue-tied when called on in class. As a result, they now fear any situation where they might be called upon to speak in public.

Scrutiny Fear People with scrutiny fear have a heightened anxiety about situations where they might be watched. Both scrutiny fear and state-anxiety can be addressed through cognitive restructuring (CR).

Cognitive Restructuring Overcoming PSA is as much a matter of changing one s attitude as it is developing one s skills as a speaker. Cognitive restructuring (CR) is an internal process through which individuals deliberately adjust their perceptions of an action or experience. Cognitive Restructuring is a three-step, internal process: Identify objectively what you think Identify any inconsistencies between perception and reality Replace destructive thinking with supportive thinking

Cognitive Restructuring in Action: Fear of Being the Center of Attention If you fear having everyone s eyes on you as you speak, recall a time when you have been an audience member when someone spoke. Did you look at the speaker? If so, why? Was it because in the United States, direct eye contact is the primary way that audience members demonstrate that they are listening to the speaker? Next, reframe how it might feel to speak in front of an audience where everyone is looking at you. They re looking at you as a sign of respect, not in order to watch for any sign of a misstep.

Cognitive Restructuring in Action: Fear of Judgment Do you fear that the audience will judge you harshly if you misspeak, or they don t like the sound of your voice, or don t believe that you know what you re talking about? Recall your own expectations when you listened to someone speak. Did you expect the speaker to be flawless and riveting? Probably not. Next, recall how you reacted after a speaker mispronounced a word or lost her train of thought. Did you feel empathy for the speaker? Did you even remember that the speaker mispronounced a word or lost her train of thought? Finally, reframe how the audience might judge you if you mispronounce a word or lose your train of thought. Chances are that they won t even notice your gaff.

Techniques for Building Confidence Practice, Practice, Practice A speaker s nervousness is linked to her level of preparation. More practice results in less nervousness. While thinking about your presentation can be helpful, that sort of preparation will not give you a sense of what you are actually going to say. Sufficient practice for public speaking recreates those real-life scenarios.

Preparing Well: Visualize Success Just as athletes and performers are coached to visualize what they are trying to do in order to perform correctly, speakers should prepare by visualizing success. As you practice, Visualize yourself presenting with confidence to a receptive audience. See your relaxed facial expressions and hear your confident tone of voice. Imagine yourself moving gracefully, complementing what you say with expressive gestures. the audience nodding appreciatively and giving thoughtful consideration to your points because they really get it. When you can honestly envision yourself performing at this level, you are taking an important step toward achieving that goal.

Preparing Well: Avoid Gimmicks Don t Imagine the audience in their underwear as a way to make them seem less frightening. Concentrating on anything other than what you are doing is distracting and not beneficial at all. Practice in a mirror. Watching yourself perform in a mirror will focus your attention on your appearance first and on what you express second. You want to become more familiar with the how much material you have to present, the order in which you plan to present it, and the phrasing you think would be most effective to express it.

Preparing Well: Breathe and Release Breathe and Release is a relaxation technique to calm nervous tension. How to Breathe and Release Imagine the nervousness within your body and the energy bubbling inside you, like boiling water. Inhale deeply while imagining that your breath is like a vacuum, inhaling all of the bubbling liquid. Release the energy by exhaling slowly while deliberately relaxing your upper body, all the way from your fingertips to your shoulder blades. As you continue to breathe, imagine how keeping any part of your upper extremities tense would result in a kink in value that releases your nervous energy. Complete relaxation is the key to success.

Preparing Well: Minimize what You Memorize Avoid writing an entirely scripted version of the presentation. A speech outline is not a monologue or manuscript; it is a guideline and should be used as a roadmap for your speech. If you are completely focused on the integrity of scripted comments, then you will be unable to read and react to your audience in any meaningful way. A well-prepared speaker is conversant regarding her topic; she knows the basic facts so that she could hold a conversation about it with her audience. Being conversant allows for freer, more fluid communication, with no stress associated with your ability to remember the exact words you wanted to use, and gives the speaker the best chance to recognize and react to audience feedback.

Preparing Well: Practice Out Loud The out-loud dress rehearsal is the single, most important element to your preparation. Practicing out loud from beginning to end allows you to listen to your whole speech and properly gauge the flow of your entire presentation, and accurately estimate the length of your speech. Practice with the goal of becoming conversant in your topic, not fluent with a script. During your initial practice consider these questions: Where, during your presentation, are you most and least conversant? Where, during your presentation, are you most in need of supportive notes? What do your notes need to contain? Prepare by speaking and listening to yourself, rather than by writing, editing, and rewriting.

Preparing Well: Customize Your Practice to Deal with Your PSA Reflect on what triggers your PSA, write down the concerns and put them into a priority order. Next, consider your current method of preparation. Remember that dealing with PSA often involves breaking a mental habit, so it might be a good idea to change what you have done previously.