Settler Colonialism and Carcerality: Disrupting Indigenous Relationships and Territories

This study delves into the impact of settler colonialism on Indigenous peoples, focusing on the immobilization and movement imposed on them through carceral spaces. It explores the intersections of official and unofficial carceral spaces, shedding light on the disrupting effects on Indigenous relationships to land and claims to territory. Additionally, the research examines the dimension of time within the context of colonialism, highlighting how settler societies perceive Indigenous people as out of place and time. Overall, it offers a critical analysis of the historical and contemporary implications of settler colonial practices.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Doing Colonial Time Doing Colonial Time Adam J Barker & Emma Battell Lowman- University of Hertfordshire Image: Mohawk Industrial School, Brantford, Ontario

Overview Overview Personal position settlers & decolonization Research expertise Previous work How places become storied & how settlers come to see themselves as belonging in a place The importance of story, language, place, and relationships to understanding settler colonialism Ties between settler identities & material & cultural landscapes (deathscapes)

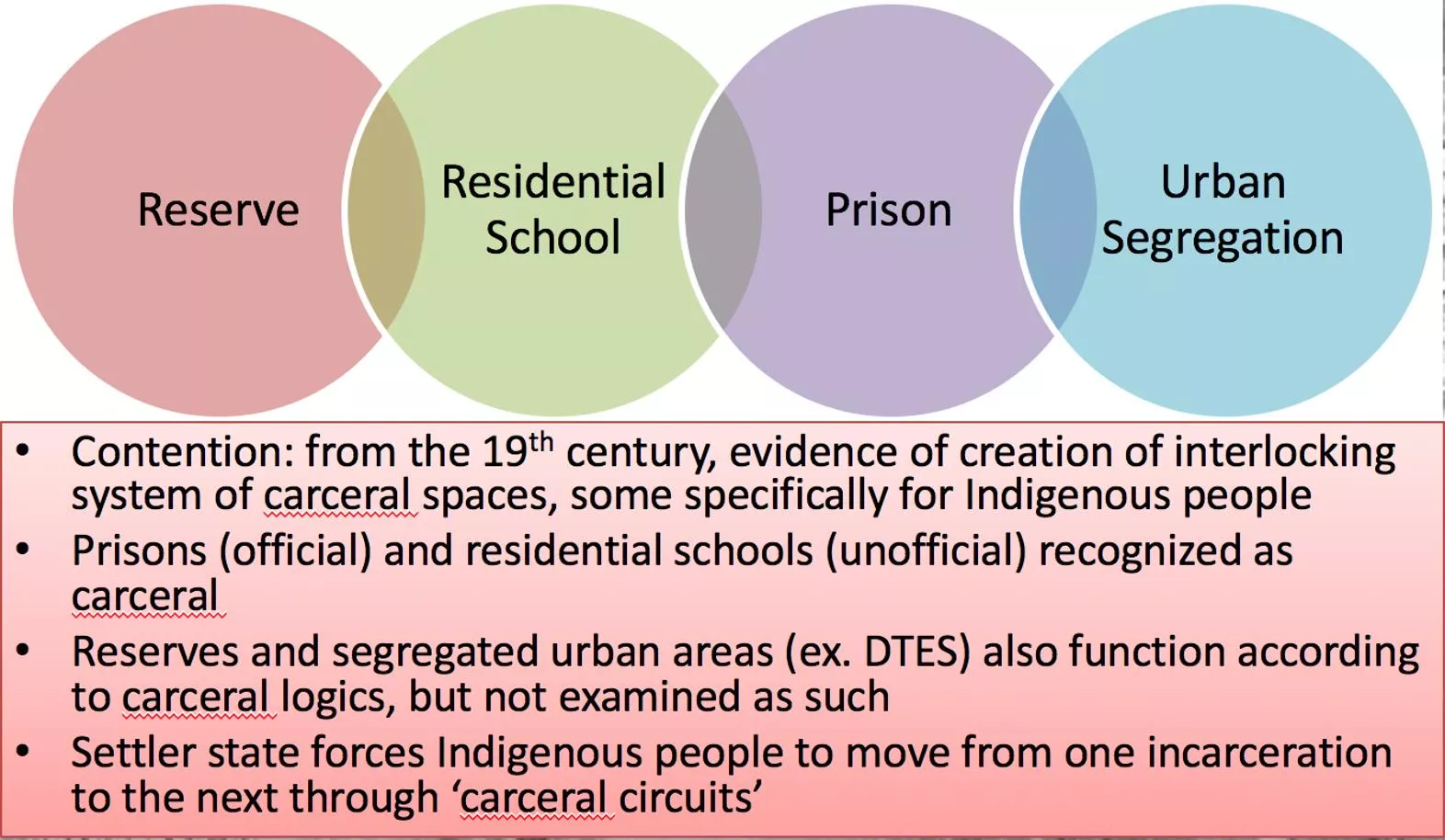

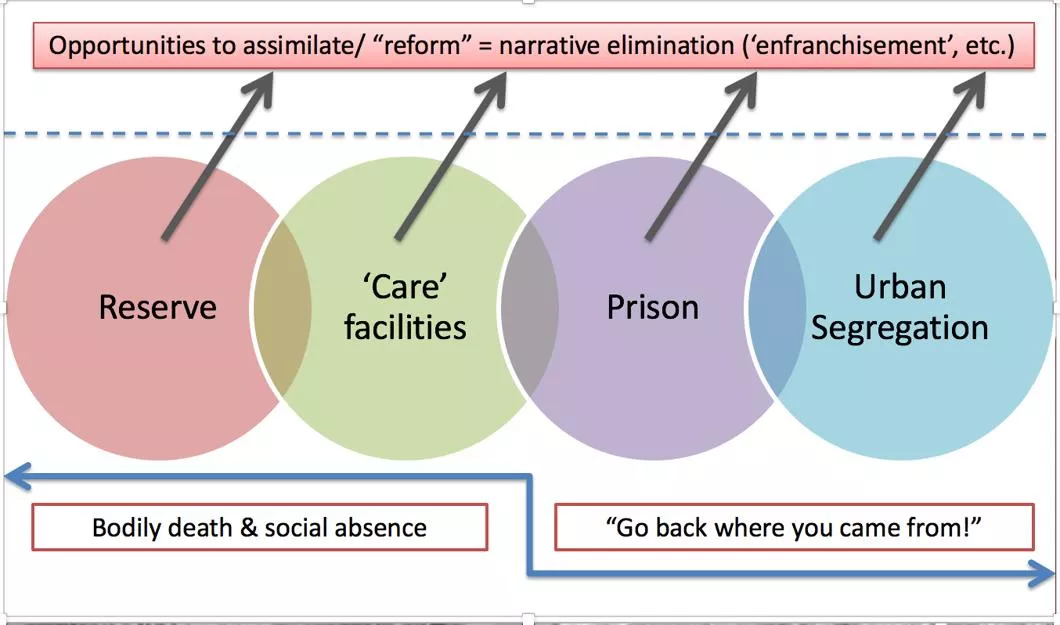

Settler Colonial Settler Colonial Carcerality Carcerality Building on previous work (1st Carceral Geog Conference, AAG 2017) Settler colonial carcerality immobilization of Indigenous peoples as method of disrupting relationships to place & claims to territory Interlocking carceral spcaes official (prisons), unofficial (schools, hospitals), unrecognized (urban segregation, rural invisibility) Carceral churn settler society imposes movement but not mobility; Indigenous bodies repeatedly moved from one carceral space to the next until they self-eliminate (assimilate) or experience bodily death But: what about time?

Time, Colonialism & The Time, Colonialism & The Carceral Carceral Kevin Bruyneel: Settler societies see Indigenous people as both out of place & out of time Circuits of carcerality overlap with circuits of capital Experience of modernity efficiency & regularization Time and the Other (Fabian, 1983) Indian time & temporal racism

Research Framework Research Framework Location: Niagara-Haldimand region Our homelands personal responsibility Six Nations of the Grand River and Haldimand Grant Material landscape Transport & communication infrastructure Settlement patterns & private property Cultural landscape Racism & exclusion Settler colonial memory & forgetting Right: a map of the original Haldimand Grant to the Haudenosaunee (in grey), and present day Six Nations of the Grand River reserve (in orange) - Image courtesy of Six Nations Lands & Resources Development Office

Carcerality Carcerality & Progress & Progress Example 2: Grand River Navigation Company Example: Upper Canada Centennial 1893 speeches celebrate Lord Simcoe, first Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada Mythology: Simcoe s canoe trip choosing the capital, Simcoe travelled around Lake Ontario by canoe because there were no roads Historical reconstruction of Indian trails forgetting in action records of British use of these roads in early 1800s, so where did they/the memory of them go? New roads built over old appropriation of network, erasure of Indigenous labour & presence Indian Department of Upper Canada authorizes creation of canal system for shipping on the Grand River Company (illegally) funded by Six Nations funds held in government trust Company is corrupt, mismanaged, goes bankrupt Six Nations lose their money, do not benefit from canals, but river traffic now changed to meet needs of settler economy

Corduroy Road Corduroy Road Larger project: Scoping research in summer of 2017 & 2018 Identification of corduroy roads as important but temporary feature of settler colonial landscape Investigation into how changes in movement indicate changes in power affecting relative mobility in settler colonial contexts, how particular colonial memories are imposed on the landscape Includes strands on consideration of bodies & death, public history & heritage, memorials & social narrative, and invisible violence & carceral erasure An uncovered corduroy road in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada underneath present day King Street, the main urban artery image via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons

Questions & Comments Questions & Comments