Understanding Behavioral Finance Puzzles in Normal People's Finance

Behavioral finance puzzles delve into challenges like the dividend puzzle, the disposition puzzle, dollar-cost averaging, and time diversification. These puzzles combine wants for different benefits, cognitive and emotional errors, tools for correction, and implications of various theories for decision-making. The dividend puzzle, for instance, questions the reasons behind corporations paying dividends and investors' focus on them, highlighting conflicting desires between saving and spending.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Finance for Normal People Chapter 7: Behavioral Finance Puzzles: The dividend puzzle, the disposition puzzle, and the puzzles of dollar-cost averaging and time-diversification

Behavioral finance puzzles Four important financial puzzles: The dividend puzzle is about the preference for spending dividends while refraining from selling stocks and spending their proceeds The disposition puzzle is about the disposition to realize gains quickly but procrastinate in the realization of losses The puzzles of dollar-cost averaging and time-diversification are about their popularity among investors despite faults in the standard arguments that underlie them

Behavioral finance puzzles The solution to these puzzles combine: 1. Wants for utilitarian, expressive, and emotional benefits, presented in Chapter 2 2. Cognitive and emotional shortcuts and errors in Chapters 3 and 4 3. Tools for correcting errors in Chapter 5 4. Implications of expected utility and prospect theories for life- evaluation, experienced happiness, and choices in Chapter 6

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle Why do corporations pay dividends? Why do investors pay attention to dividends? ... The harder we look at the dividend picture, the more it seems like a puzzle, with pieces that just don t fit together Fischer Black, Journal of Portfolio Management, 1976

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle Wants for utilitarian, expressive, and emotional benefits Saving provides utilitarian, expressive and emotional benefits and so does spending, but the two wants conflict Distinctions between capital and dividends help us balance our conflicting saving and spending wants and regulate them

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle How normal-ignorant investors frame capital and dividends

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle How rational and normal-knowledgeable investors frame capital and dividends

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle Framing and Mental Accounting What is the difference between $1,000 in homemade dividends from the sale of shares and $1,000 from a cashed company-paid dividend check?

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle Self-control How is self control helped by separate mental accounts for capital and income and a rule of spend income but don t dip into capital ? How do company-paid cash dividends facilitate exercise of self-control? How do stock dividends facilitate exercise of self-control?

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle Hindsight, Regret, and Pride What is the regret potential of company-paid cash dividends and homemade dividends?

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle Framing in prospect and expected-utility theories Choose between: A. $2 today and a 50-50 chance of $50 or $54 tomorrow B. Nothing today and a 50-50 chance of $52 or $56 tomorrow

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle Framing in prospect theory Consider an investor who bought the stock for $40 A. $2 dividend plus a 50-50 chance for a capital gain of either $10 or $14 B. 50-50 chance for a capital gain of $12 or $16

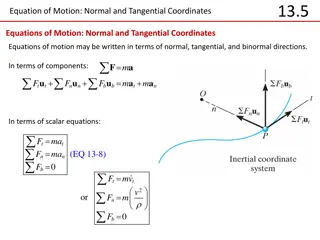

Figure 7 Figure 7- -1a: Comparing prospect theory gain 1a: Comparing prospect theory gain- -loss utility with dividends are paid and not paid paid and not paid The case where the price of the share increased The case where the price of the share increased loss utility with dividends are Units of Gain-Loss Utility 357 287 80 $16 $2 $10 Gains Losses

Behavioral finance puzzles The dividend puzzle Framing in prospect theory Consider an investor who bought the stock for $70 A. $2 dividend plus a 50-50 chance for a capital loss of either $16 or $20 B. 50-50 chance for a capital loss of $14 or $18

Figure 7 Figure 7- -1b: Comparing prospect theory gain 1b: Comparing prospect theory gain- -loss utility with dividends paid and not paid and not paid The case where the price of the share declined The case where the price of the share declined loss utility with dividends paid Units of Gain-Loss Utility 80 -$14 -$20 Losses Gains $2 -546 -599

Behavioral finance puzzles The Disposition Puzzle Rational investors are quick to realize losses and slow to realize gains (why?) Yet many normal investors display a disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long Why do investors display that disposition? This is the disposition puzzle Do you display a disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long ?

Behavioral finance puzzles The Disposition Puzzle Wants for avoiding regret Realizing losses imposes the emotional costs of regret whereas realizing gains yields the emotional benefits of pride

Behavioral finance puzzles The Disposition Puzzle Hindsight shortcuts and errors We bought a share for $100 because we saw, in foresight, its price increasing to $140 But now, in hindsight, we remember all the warning signs displayed in plain sight on the day we bought our share

Behavioral finance puzzles The Disposition Puzzle Hindsight, regret, and responsibility We experience disappointment when a broker who bears responsibility for choosing stocks for us makes a choice that sustains losses But we suffer regret when we ourselves bear responsibility for that choice

Behavioral finance puzzles The Disposition Puzzle Methods for overcoming the disposition effect Transfer your assets Harvest your losses Stop-loss orders

Behavioral finance puzzles The disposition puzzle Framing in expected-utility and prospect theories You bought a share of stock yesterday for $100 It is selling at $60 today You face a 50-50 chance that the share s price would increase by $40 tomorrow to $100 or decline by a further $40 to $20 The capital gains tax rate is 20% Would you realize your loss?

Behavioral finance puzzles The disposition puzzle Framing in prospect theory Choose between: A. Sell the share today thereby realizing the $40 loss B. Hold the share for another day, accepting a 50-50 chance of losing a total $80, or getting-even, losing $0

Figure 7 Figure 7- -2a: Gain 2a: Gain- -loss utility associated with options A and B loss utility associated with options A and B Units of Gain-Loss Utility -$40 -$80 Losses Gains -140 -175

Behavioral finance puzzles The disposition puzzle Framing in prospect theory You bought a share of stock yesterday for $60 It is selling at $100 today You face a 50-50 chance that the share s price would increase by $40 tomorrow to $140 or decline by $40 back to $60 The capital gains tax rate is 20% Would you realize your gain?

Behavioral finance puzzles The disposition puzzle Framing in prospect theory Choose between: C. Sell the share today thereby realizing a $40 paper gain. D. Hold the share for another day, accepting a 50-50 chance of gaining a total of $80 or gaining $0

Figure 7 Figure 7- -2b: Gain 2b: Gain- -loss utility associated with options C and D loss utility associated with options C and D Units of Gain-Loss Utility 95 60 $40 $80 Losses Gains

Behavioral finance puzzles The disposition puzzle Countering the disposition effect Rules are a self-control device facilitating the realization of losses

Behavioral finance puzzles The disposition effect Countering the disposition effect Self-control and outside control Magic words such as transfer your assets or harvest your losses The role of December The roles of regret, fear, sadness, and disgust

Behavioral finance puzzles The disposition effect The disposition effect among corporate managers Corporate managers are disposed to throw good money after bad into losing projects Some of the reluctance, but not all, is due to conflicts of interest Project review committees and workout units can counter the disposition effect

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzles of dollar-cost averaging and time-diversification The dollar-cost averaging puzzle centers on the argument that utilitarian benefits make investment by dollar-cost averaging better than investment by lump-sum The time-diversification puzzle centers on the argument that the risk of stocks declines as the investment horizon increases

Behavioral finance puzzles Time-diversification centers on the belief that the risk of stocks declines as the investment horizon increases That belief is shared by amateur and professional investors alike, often accompanied by graphs showing that the probability of stock market gains increases as their holding periods increases

Figure 7-3: Proportion of stock market periods with gains by time horizon (1926-2015) 100 75 Proportion (%) 67 of 90 Periods 76 of 86 Periods 76 of 81 Periods 71 of 71 Periods 76 of 76 Periods 50 25 0 1 5 10 15 20 Investment Horizon (years)

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzles of dollar-cost averaging and time-diversification The solutions to the puzzles combine: 1. Wants for utilitarian, expressive, and emotional benefits 2. Application of expected utility and prospect theories 3. Roles of cognitive and emotional shortcuts and errors 4. Tools for correcting errors

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of dollar-cost averaging Framing and expected-utility and prospect theories in dollar- cost averaging An investor with $2,000 in cash he has chosen to invest in stocks because stocks are likely to yield higher long-term wealth than cash, even though they also impose higher variance of wealth This choice is consistent with expected-utility theory if the investor s variance-aversion is not too high

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of dollar-cost averaging Framing and expected-utility and prospect theories in dollar- cost averaging Loss-aversion, a feature of prospect theory, might deter our investor from buying stocks Dollar-cost averaging overcomes loss-aversion in a frame that highlights gains and obscures losses

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of dollar-cost averaging Average cost of shares held at the end of the two periods: $2000/100 = $20 Average price at which shares were bought during the two periods: (50 + 12.5)/2 = $31.25 Table 7-1: Dollar-Cost Averaging Amount Invested 1 2 $1000 Total $2000 Price per Share Number of Shares Bought Period $1000 50 20 80 100 12.5

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of dollar-cost averaging Pride and regret in dollar-cost averaging Investors anticipate the emotional benefits of pride and emotional costs of regret when they make choices Investors mitigate their anticipated emotional costs of regret when they convert only one part of their cash into shares of stock today

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of dollar-cost averaging Self-control in dollar-cost averaging The strict rules of dollar-cost averaging combat self-control lapses, compelling investors to stick to the stock-buying or stock-selling plan

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of dollar-cost averaging Reverse dollar-cost averaging An investor with stocks who converts her entire amount into cash today bears less variance-risk and loss-risk tomorrow than when she follows reverse dollar-cost averaging, converting only a portion into cash and keeping the other in stocks Risk reduction cannot be the rationale for both dollar-cost averaging and reverse dollar-cost averaging

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of dollar-cost averaging Prospect theory The return on cash is zero $2,000 in stocks will, with equal probabilities, either increase by $600 to $2,600 tomorrow or decrease by $280 to $1,720 The reference point of John is $2,000 in cash He frames the choice as between A and B A. Keep in cash: A sure gain of $0 B. Convert cash into stocks: A 50-50 chance to gain $600 or lose $280

Figure 7-4a: Choice to hold $2,000 in cash or convert it into stocks Units of Gain-Loss Utility 80 -280 600 Losses Gains -124

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of dollar-cost averaging The reference point of Jane is $2,000 in stocks She frames the choice as between C and D C. Convert stocks into cash: A 50-50 chance for an (opportunity) gain of $280 if the price of shares declines or an (opportunity) loss of $600 if the price of shares increases. D. Keep in stocks: A sure (opportunity) gain of $0

Figure 7-4b: Choice to hold $2,000 in stocks or convert it into cash Units of Gain-Loss Utility 47 -600 280 Losses Gains -160

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of time-diversification Framing and expected-utility and prospect theories in time- diversification The time-diversification puzzle is related to the equity premium puzzle $1,000 in Treasury bills at the end of 1925 compounded to a mere $12,720 by the end of 1995, whereas $1,000 in stocks compounded to $842,000 Why are long-term investors reluctant to invest large proportions of their portfolios in stocks when the long-term expected returns from them are so much higher than those of Treasury bills?

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of time-diversification Framing and expected-utility and prospect theories in time- diversification Jeremy Siegel and Richard Thaler offered several possible solutions to the equity premium puzzle but favored the myopic loss-aversion, rooted in prospect theory s loss-aversion The frequency of losses varies by the length of periods over which returns are observed Losses are more frequent over short periods than over long periods Investors who observe returns over short periods might exhibit myopic loss- aversion - misled into the belief that losses are more likely over long periods than they truly are

Figure 7-5a: Distribution of returns of stocks and bonds during 1-Year investment horizons (Bond returns in black and stock returns in white) 80 60 40 Return (%) 20 0 -20 -40 Lowest to Highest Returns (means of 200 simulated returns in each group)

Figure 7-5b: Distribution of returns of stocks and bonds during 30-Year investment horizons (Bond returns in black and stock returns in white) 25 20 Return (%) 15 10 5 0 Lowest to Highest Returns (means of 200 simulated returns in each group)

Behavioral finance puzzles Framing and expected-utility and prospect theories in time-diversification The median allocation to stocks among those who saw the 1-year chart was 40%. The median allocation to stocks among those who saw the 30-year chart was 90% More recent evidence indicates, however, that myopic loss-aversion has little effect on investment choices People invest as much in stocks when they see one-year or long-horizon historical return distributions, but they invest less in stocks when they see no historical return distributions This suggests that lack of knowledge of high historical stock returns rather than myopic loss-aversion makes investors excessively pessimistic about future stock returns

Behavioral finance puzzles The puzzle of time-diversification Framing errors in time-diversification Paul Samuelson argued that the advocacy of time-diversification is built on framing errors that mislead investors into an illusory happy ending, as if the probability of losses over the long-run is zero Consider an investor who invests $1,000 in a portfolio with a 50 50 chance to gain 20% or lose 10% each year The investor has a 50% probability of losing money if her horizon is one year, but she has only a 25% probability of losing money if it is two years

Figure 7-6: Probabilities of losing money and amounts of money that can be lost $1,440 $1,200 $1,080 $1,000 $900 One-Year Horizon (50% chance for a $100 loss) $810 Two-Year Horizon (25% chance for a $190 loss)