Understanding Judicial Review and Judicial Activism

Judicial review provides a mechanism for judicial oversight of administrative actions, focusing on legality rather than merits. Grounds for judicial review include illegality and irrationality. Illegality involves decision-makers acting beyond their authority, while irrationality deals with decisions that are unreasonable or defy logic. These concepts are central to the function of judicial control in administrative law.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

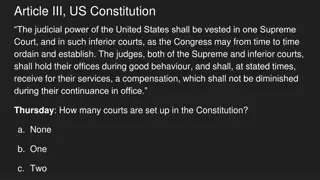

MONSOON INTERNSHIP PROGRAMME BLOG ON JUDICIAL REVIEW AND JUDICIAL ACTIVISM SUBMITTED BY- MANVI (MIP15)

J U D I C I A L R E V I E W DEFINITION: "Judicial review, provides the means by which judicial control of administrative action is exercised. The subject matter of every judicial review is a decision made by some person (or body of persons) whom I will call the "decision-maker" or else a refusal by him to make a decision." Judicial review is different from an appeal. The distinction is that an appeal is concerned with the merits of the decision under appeal while judicial review is concerned only with the legality of the decision or act under review.

GROUNDS FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service [1984] UKHL 9, or the GCHQ case Lord Diplock classified the grounds on which administrative action is subject to judicial control under three heads, namely, 'illegality', 'irrationality', and 'procedural impropriety'. He also said that further grounds may be added as the law developed on a case-by-case basis.

(A)ILLEGALITY Illegality as a ground for judicial review means that the decision-maker must understand correctly the law that regulates his decision-making power and must give effect to it. Whether he has or not is a question to be decided in the event of dispute by judges. This would mean that when a power vested in a decision-maker is exceeded, acts done in excess of the power are invalid as being ultra vires (substantive ultra vires). An example would be where a local council, whose power is derived from statute, acts outside the scope of that authority. See: Bromley Council v Greater London Council (1983). Government Ministers have also sometimes acted outside their authority. See: R v Home Secretary, ex parte Fire Brigades Union (1995).

(B) IRRATIONALITY By irrationality as a ground for judicial review, Lord Diplock in the GCHQ Case (1985) meant what is referred to as Wednesbury unreasonableness. In Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corp (1948) the Court of Appeal held that a court could interfere with a decision that was 'so unreasonable that no reasonable authority could ever have come to it'. Lord Diplock in the GCHQ Case said that this 'applies to a decision which is so outrageous in its defiance of logic or of accepted moral standards that no sensible person who had applied his mind to the question to be decided could have arrived at it. Case examples include: Strictland v Hayes Borough Council (1896) R v Derbyshire County Council, ex parte The Times (1990) This ground has been used to prevent powers from being abused by, for example, exercising a discretion for an improper purpose or without taking into account all relevant considerations.

(C) PROCEDURAL IMPROPRIETY Procedural impropriety as a ground for judicial review covers the failure by the decision-maker to observe procedural rules that are expressly laid down in the legislation by which its jurisdiction is conferred, or a failure to observe basic rules of natural justice, or a failure to act with procedural fairness (procedural ultra vires). An example of procedural rules not being followed is: Aylesbury Mushroom Case (1972).

PROCEDURE FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW The procedure of application for judicial review is contained in the Supreme Court Act 1981 and Order 53 of the Rules of the Supreme Court, and is in two stages. Leave of the High Court is needed for every application for judicial review. Leave is generally a matter decided by a single judge without a hearing, but if necessary the decision may be made after a brief hearing. The application for leave is made ex parte, ie without notice to the other side, by filing a notice of application with an affidavit verifying the facts relied on, in the Crown Office. Where leave is refused without a hearing, the application for leave may be renewed in open court before a single judge or a Divisional Court. It may be further renewed in the Court of Appeal. When leave is obtained the hearing of the application for judicial review takes place before a single judge of the Queen's Bench Division or a full Queen's Bench Divisional Court in cases which involve criminal law. Appeals against a decision can be made to the Court of Appeal and from there to the House of Lords.

Applications for judicial review must be brought within a time limit and the applicant must have LOCUS STANDI: By Order 53, an application for judicial review shall be made promptly, and in any event within three months from when grounds for the application first arose, unless there is good reason for extending the period. At the stage when leave is sought for an application for judicial review, the court must not grant leave 'unless it considers that the applicant has a sufficient interest in the matter to which the application relates' (s31(3) of the Supreme Court Act 1981).

REMEDIES If an application for judicial review is successful the following remedies are available. Firstly, the prerogative orders (mandamus, prohibition and certiorari): Mandamus is an order from the High Court commanding a public authority or official to perform a public duty. Prohibition is an order issued primarily to prevent an inferior court or tribunal from exceeding its jurisdiction, or acting contrary to the rules of natural justice. Certiorari is an order quashing decisions by inferior courts, tribunals and public authorities where there has been an excess of jurisdiction or an ultra vires decision; a breach of natural justice; or an error of law. By setting aside a defective decision, certiorari prepares the way for a fresh decision to be taken.

Judicial Activism Judicial activism is the term used to describe the actions of judges who go beyond their constitutionally prescribed duties of applying law to the facts of individual cases, and "legislate" from the bench. These judges create new constitutional rights, amend existing ones, or create or amend existing legislation to fit their own notions of societal needs.

Judicial Activism Example when a court "finds" a "right of privacy" hidden in the "penumbras" and "emanations" of the Constitution, and later expands this "right of privacy" into the right to abortion; that's judicial activism. Here are some other examples: When a court rules that the First Amendment ("Congress shall make no law ... ") suddenly means that "the states shall make no law" and creates a new constitutional "wall of separation" between church and state; When a court rules that "evolving constitutional standards" mandates a right to same-sex marriage, contravening 200 years of state law and centuries of tradition.

Debates about Judicial Activism Detractors of judicial activism charge that it usurps power of the legislature, thereby diminishing the rule of law and democracy. They argue that an unelected judicial branch has no legitimate grounds to overrule policy choices of duly elected representatives, absent a real conflict with the constitution Defenders of judicial prerogatives say that many cases of "judicial activism" merely exemplify judicial review, and that courts must uphold the constitution and strike down any statute that violates the constitution. They say that it is the duty of courts to protect minority rights and to uphold the law, notwithstanding the political sentiments of the day, and that constitutional democracy is far more than just majority rule.

Areas of judicial activism During the past decade, many instances of judicial activism have gained prominence. The areas in which judiciary has become active are health, child labour, political corruption, environment, education, etc. Through various cases relating to Bandhua Mukti Morcha, Bihar Under trials, Punjab Police, etc he judiciary has shown its firm commitment to participa-tory justice, just standards of procedures, immediate access to justice, and preventing arbitrary state action.