Understanding Audience Reactions to Media Personae

Audience reactions to media personae vary based on factors such as perceived realism, suspension of disbelief, character personality, and viewer affinity. This analysis explores how audience members engage with characters in media, evaluating morality, admiration, and perspective within the portrayed world.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Audience reactions to media personae

Audience members can react in many ways to media personae The reaction/perspective will depend on a variety of factors. A few significant questions include: Does the audience member treat the character as at least somewhat realistic? Does the audience member suspend disbelief in relation to the portrayed environment? To the character? To the actor/anchor/etc.? What impression does the audience member have of the character s personality? Is the viewer/audience member drawn to the character in some way? As a role model? As a friend?

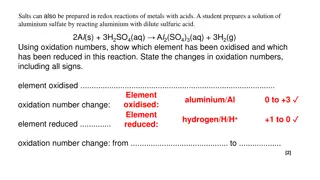

Does the audience member treat the personae as realistic in some way? This does not require that the audience member perceive the persona to exist as a real person when the show ends. The persona must be capable of acting as an appropriate character within the constraints of the program-world and the program-world must be accepted in the sense of suspension of disbelief. Robot

What impression does the audience member have of the character s personality? Viewer/listeners/audience members evaluate the morality of characters, etc. through their words and deeds and, sometimes, their thoughts as revealed by the author/director, etc. Attribution

Audience members tend to affiliate with those they admire, but there are exceptions Large numbers of viewers liked J.R. Ewing the best among characters on Dallas Viewer evaluations vary along a wide contiuum, from adoration (fan clubs) to disgust (chearing at the dismemberment of villains, etc.)

What position does the audience member take in relation to the text and/or the character? Does the audience member maintain the position of external spectator, aware of the fictitious nature of the presentation? Does the audience member take a perspective from inside the portrayed world? Character within the story Internal spectator Does the audience come to inhabit the body of a character, living within the on-screen (or in- story, or on-radio) persona?

Does the viewer/audience member react to the character in some way? The evidence seems to indicate that an audience member may be attracted to, repulsed by, terrified of, or in some other emotional way, affected by the persona portrayed.

What is identification? Identification is where the audience member takes on the role of the persona/character vicarious experience of things that we could not otherwise have any access to [Cohen, 2002] Audience members may try on others identities, etc. Seen as both natural and troubling in teenagers Thought to be especially common in online role- playing

Identification and fictional involvement Identifying with a character: provides a point of view on the plot leads to an understanding of character motives brings about an investment in the outcome of events generates a sense of intimacy and emotional connection with a character [Source: Cohen, 2006]

Identification is fleeting and varies in intensity (Wilson, 1993), a sensation felt intermittently during exposure to a media message. While identifying with a character, an audience member imagines him- or herself being that character and replaces his or her personal identity and role as audience member with the identity and role of the character within the text. While strongly identifying, the audience member ceases to be aware of his or her social role as an audience member and temporarily (but usually repeatedly) adopts the perspective of the character with whom he or she identifies. Cohen, 2006

Wishful identification A second form of identification is more lasting. Audience members have stated that they wish to be like a character/persona. That is, they would like to emulate one or more qualities exhibited by the character.

An important basis for identification is when the audience member understands and then adopts the goals of a character. The audience member then reacts to the attempt to reach those goals within the environment of the story, etc. Cohen, 2006

Directors and writers create characters with whom audiences are meant to interact . . . . Unlike identification with parents, leaders, or nations, identification with media characters is a result of a carefully constructed situation. . . . it is important to note that identification is a response to communication by others that is marked by internalizing a point of view rather than a process of projecting one s own identity onto someone or something else.

What leads to identification? Production features that lead the audience member to adopt the character s perspective An audience member s fondness for a character A realization of similarity of the character to oneself on the part of the audience member These lead to a psychological merging (Oatley, 1999) or attachment, in which the audience member comes to internalize the characters goals within the narrative. Cohen

The audience member then empathizes with the character and adopts the character s identity. As the narrative progresses, the audience member simulates the feelings and thoughts appropriate for the events that occur. Cohen

Four dimensions of identification The first is empathy or sharing the feelings of the character (i.e., being happy; sad; or scared, not for the character, but with the character). The second is a cognitive aspect that is manifest in sharing the perspective of the character. Operationally this can be measured by the degree to which an audience member feels he or she understands the character and the motivations for his or her behavior. The third indicator of identification is motivational, and this addresses the degree to which the audience member internalizes and shares the goals of the character. Finally, the fourth component of identification is absorption or the degree to which self-awareness is lost during exposure to the text. [Cohen, 2002]

Encouraging identification Writing, acting, and directing must be of sufficient quality partly achieved by offering an illusion of reality relevance and resonance of issues and events

Identification may be ended or interrupted when the audience member is made aware of him- or herself through an external stimuli (e.g., the phone rings), a textual stimuli (e.g., a change of camera angle or a direct reference to the reader), or the end of the story. Cohen

Identification may lead to increased liking for or imitation of a character especially a positive character. Identifying with characters who are evil or very violent may evoke some understanding or even sympathy for them during reading or viewing but strongly identifying with such a character is likely to cause dissonance, guilt, or even fear.

Identification Parasocial interaction Liking, similarity, affinity Imitation Emotional and cognitive, alters state of awareness Nature of process Interactional Attitude Behavior Basis Attraction Perception of character and self Modeling Understanding and empathy Positioning of viewer As self As self As learner (self as other) As character Associated phenomena Attachment to character and text, keeping company Fandom, realism Learning, reinforcement Absorption in text, emotional release Positioning of viewer As self As self As learner (self as other) As character

Influence of medium Literature invites identification with hero/protagonist and, to a lesser extent, narrator Film encourages spectator role, but may foster identification with protagonist or camera narrator Television may be too uninvolving to lead to identification at all Domestic, chaotic viewing situation

Antecedents to identification Similarity and homophily Children: Identify with role models who they would like to be more than who they are like Especially children over 8 Attitude homophily positively related to identification Identified with child characters (similar to themselves) Exception: girls often identified with male characters Identified with animals Teens Often chose opposite-sex characters based on romantic or sexual attraction Favored young adult rather than teen characters

Working-class women identified with upper class women on Dynasty more than did middle class women 1/5 of German men chose female favorite TV person compared to 1/3 German women choosing male Aggressive children reported higher homophily and identification with aggressive characters

it seems that whereas similarity in attitudes predicts character choice, simple demographic similarity is not a good predictor. People often identify with characters that represent what they wish to be or to whom they are attracted, rather than what they are. It also seems that psychological similarity is more important than demographic similarity in shaping identification. [Source: Cohen, 2006]

Traits of characters that encourage identification Men: Boys and girls like them for their intelligence, girls like them for sense of humor Women: Boys and girls judged them based on their looks Heroes identified with more often than villains Exception: many preferred J.R. Ewing In general, strength, humor and physical attractiveness are preferred Much like in real life In general, much left to be determined in why people are attracted to characters

Viewer characteristics Findings on gender ambiguous Women higher in parasocial interaction Findings concerning age are ambiguous Young, teens and older adults appear to have stronger parasocial relationships Does not appear to be related to poor interpersonal relations Some indication that those anxiously attached individuals who desire strong relationships but have trouble developing secure and stable relationships have the strongest parasocial relationships [source: Cohen, 2006]

Identification effects Increase enjoyment of fiction Persuasion Memorability Modeling and imitation Learning Reduced critical stance

In sum, identification is an active psychological state, but neither stable nor exclusive. It is one of many ways we respond to characters, and one of many positions from which we experience entertainment. The development and strength of identification depend on multiple factors: the nature of the character, the viewer, and the text (directing, writing, and acting). Finally, identification is part of a a larger set of responses to entertainment, ways in which we become engrossed and delighted by the fortunes and misfortunes of others. [Source: Cohen, 2006]

Parasocial interaction Horton and Wohl used the term in 1956

Parasocial interaction Developing a relationship with a media persona that exhibits some of the characteristics of interpersonal relationships Liking, dislike Talking to the character/yelling at the character Feeling as though the character is addressing her individually Seeing the persona as a friend Caring about the persona Missing the persona when skipping an episode, etc.

Superhero play One researcher observed children's superhero play in a school setting and found that boys created more superhero stories than girls did, and that girls often were excluded from such play. When girls were included they were given stereotypical parts, such as helpers or victims waiting to be saved. Even powerful female X-Men characters were made powerless in the boys' adaptations (Dyson, 1994).

In one retrospective study (French & Pena, 1991), adults between the ages of 17 and 83 provided information about their favorite childhood play themes, their heroes, and the qualities of those heroes. . . . While media was the main source of heroes for kids who grew up with television, the previous generations found their heroes not only from the media, but also from direct experience, friends / siblings, and parents' occupations (French & Pena, 1991).

Childrens heros 179 children, ages 8 to 13, were surveyed from five day camp sites in central and southern California. . . . 24 African Americans, 31 Asian Americans, 74 Latinos, 1 Middle Eastern American, 2 Native Americans, 45 whites, and 2 "other." Ninety-five girls and 84 boys participated.

"We would like to know whom you look up to and admire. These might be people you know, or they might be famous people or characters. You may want to be like them or you might just think they are cool." More respondents described a person they knew (65 percent) rather than a person they did not know, such as a person or character in the media (35 percent).

Similar to the overall sample, 70 percent of the African American and 64 percent of the White children chose people they knew as heroes. In contrast, only 35 percent of the Asian American kids and 49 percent of the Latino kids named people they knew.

While both girls and boys named people they knew as their heroes, 67 percent of the girls did so as compared with only 58 percent of the boys.

One feature of role modeling is that children tend to choose role models whom they find relevant and with whom they can compare themselves (Lockwood & Kunda, 2000). Children who do not "see themselves" in the media may have fewer opportunities to select realistic role models.

African American and white children were more likely to have media heroes of their same ethnicity (67 percent for each). In contrast, Asian American and Latino children chose more white media heroes than other categories (40 percent and 56 percent, respectively). Only 35 percent of the Asian Americans respondents, and 28 percent of the Latino respondents, chose media heroes of their own ethnicity.

Overall, children in this study more often chose a same-gender person as someone they look up to and admire. This pattern is consistent across all four ethnic groups, and stronger for boys than girls. Only 6 percent of the boys chose a girl or woman, while 24 percent of the girls named a boy or man.

while boys tend to emulate same-gender models more than girls do, boys may emulate a woman if she is high in social power. Therefore, boys may be especially likely to have boys and men as role models because they are more likely to be portrayed in positions of power.

It also has been noted that college-age women select men and women role models with the same frequency, whereas college- age men still tend to avoid women role models. . . . (Gibson & Cordova, 1999).

Overall, children most frequently (34 percent) named their parents as role models and heroes. The next highest category (20 percent) was entertainers; in descending order, the other categories were friends (14 percent), professional athletes (11 percent), and acquaintances (8 percent). Authors and historical figures were each chosen by only 1 percent of the children.

African American and white children chose a parent most frequently (30 percent and 33 percent, respectively). In contrast, Asian Americans and Latinos chose entertainers (musicians, actors, and television personalities) most frequently (39 percent for Asian Americans and 47 percent for Latinos), with parents coming in second place.

Asian American and Latina girls most frequently picked entertainers (50 percent of the Asian American girls and 41 percent of the Latinas), while African American and white girls chose parents (33 percent and 29 percent, respectively). Asian American boys most frequently named a professional athlete (36 percent), African American boys most frequently picked a parent (30 percent), Latino boys most frequently chose entertainers (54 percent), and white boys picked parents (38 percent).

When asked why they admired their heroes and role models, the children most commonly replied that the person was nice, helpful, and understanding (38 percent). Parents were appreciated for their generosity, their understanding, and for "being there."

Parents were also praised for the lessons they teach their kids. A 9-- year-old Asian American boy told us, "I like my dad because he is always nice and he teaches me."

The second most admired feature of kids' role models was skill (27 percent). The skills of athletes and entertainers were most often mentioned.

The third most frequently mentioned characteristic was a sense of humor (9 percent), which was most often attributed to entertainers. For instance, a 10-year-old Latino boy picked Will Smith "because he's funny. He makes jokes and he dances funny."

Bibliography Cohen, J. (2006). Audience identification with media characters. In J. Bryant & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Psychology of entertainment (pp. 183-197). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Horton, D., & Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19, 215-229. Klimmt, C., Hartmann, T., & Schramm, H. (2006). Parasocial interactions and relationships. In J. Bryant & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Psychology of entertainment (pp. 291-313). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.