The UK and Western Productivity Puzzle: Exploring Arthur Lewis' Key

The UK and other Western countries have experienced a productivity puzzle post the Great Recession, with a slowdown in labor productivity and TFP growth. This phenomenon is attributed to constrained export demand and variations in labor market institutions across countries. The UK, in particular, has seen fluctuations in labor productivity and employment levels since the recession, presenting a unique economic scenario.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

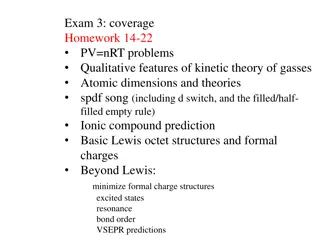

Presentation Transcript

The UK (and Western) Productivity Puzzle: Does Arthur Lewis Hold the Key? Nicholas Oulton Centre for Macroeconomics, LSE, National Institute of Economic and Social Research and Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence Email: n.oulton@lse.ac.uk Fifth World KLEMS Conference, Harvard University, 4th-5thJune, 2018 1

The Western productivity puzzle A prolonged slowdown in the growth of labour productivity and TFP over the 10 years since the Great Recession began at the end of 2007. I propose a macro explanation for the puzzle, in contrast to the current orthodoxy which looks to micro explanations. My explanation suggests two forces are at work, particularly in Europe: 1. Constrained demand for each country s exports 2. Differences in labour market institutions, leading to differences in the growth of labour input across countries. 2

The UK productivity puzzle. Or, the two economies Labour productivity (GDP per hour) fell during the Great Recession. It recovered a bit but 10 years later (2017Q3) is still only 1% above its peak in 2007Q4. BUT Unemployment is now lower than at the peak of the boom. It rose in the Great Recession, reached a peak and has been falling ever since. Employment is now 8% higher than at the peak of the boom. It fell during the Great Recession but then recovered and has continued to grow strongly. 3

GDP per hour, 2008Q1=100 1997Q1-2017Q2, log scale 100 95 90 85 80 97Q1 98Q1 99Q1 00Q1 01Q1 02Q1 03Q1 04Q1 05Q1 06Q1 07Q1 08Q1 09Q1 10Q1 11Q1 12Q1 13Q1 14Q1 15Q1 16Q1 17Q1 Note: red bar marks Great Recession Source: Office for National Statistics Productivity was growing strongly till the recession, than fell, and has only just surpassed its previous peak level in 2007Q4. 4

Unemployment, % 1997Q1-2017Q2 8 7 6 5 4 97Q1 98Q1 99Q1 00Q1 01Q1 02Q1 03Q1 04Q1 05Q1 06Q1 07Q1 08Q1 09Q1 10Q1 11Q1 12Q1 13Q1 14Q1 15Q1 16Q1 17Q1 Note: red bar marks Great Recession Source: Office for National Statistics 5

Employment (millions) 1997Q1-2017Q2, log scale 32 30 28 26 97Q1 98Q1 99Q1 00Q1 01Q1 02Q1 03Q1 04Q1 05Q1 06Q1 07Q1 08Q1 09Q1 10Q1 11Q1 12Q1 13Q1 14Q1 15Q1 16Q1 17Q1 Note: red bar marks Great Recession Source: Office for National Statistics 6

ROADMAP The Solow model and why it doesn t work after 2007 A new explanation: the neo-Lewis model , inspired by Arthur Lewis (1954), combining elements of the Solow model with the original Lewis one Empirical tests of the neo-Lewis model. Explaining the collapse in TFP growth since 2007. The role of increasing returns. 10

The Solow model (2nd year macro refresher course) = 1 : hours worked; : TFP Y AK L L A or = = = : / ; : / y Ak y Y L k K L Long run steady state growth rates (*): A = + * : constant growth rate of Y n n L 1 or A = * y 1 11

Solow model (continued) In the Solow model, the growth rate of labour is exogenous, so the productivity growth rate is independent of the growth rate of labour. In the UK case labour input has been growing at the same rate after 2007 as before. So why didn t capital intensity go on growing at the same rate? Why didn t productivity go on growing? After all, we ve got full employment. Contrast this with the Lewis model 12

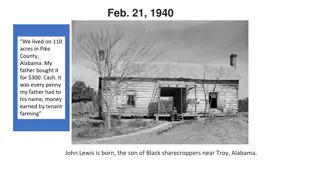

W. Arthur Lewis (1915-1991; Nobel prize 1979) 13

The neo-Lewis model Drawing inspiration from the original Lewis (1954) model, the two main features of the neo-Lewis model are: 1. Labour supply is exogenous (like in Solow) but differs across countries due to different labour market institutions and varying openness to immigrants. 2. The model possesses a good regime, where predictions are the same as Solow s, and a bad regime where foreign demand constrains a country s exports. 14

The neo-Lewis model There is one domestic good. Technology, capital and investment are the same as in the Solow model. Labour supply is exogenous and there is full employment. The economy is small and open. It exports some of its output in exchange for imports of a consumer good (i.e. 2 good model: domestic output and imports). 15

Good regime Just as in the Solow model. Productivity grows at a rate determined by the growth rate of TFP: A = * y , / ; : Y L A TFP y 1 The growth rate of productivity is independent of the growth rate of labour. 16

Bad regime: Intuition (1) By definition, the growth of labour productivity (y) is = y Y L In the bad regime, the growth of aggregate demand (Y) is constrained, so productivity growth varies inversely with the growth of labour supply. 17

Bad regime: Intuition (2) Assume labour grows at same rate before and after an export demand shock. A fall in the demand for exports (X)leads to fall in the demand for imports (M)via the intertemporal budget constraint. At given terms of trade, this leads to a fall in demand for domestically-produced consumer goods (D). If the I/Y ratio stays constant or falls, the growth of GDP slows down: X M D Y 18

The bad regime The growth of labour productivity is determined (positively) by the growth of foreign demand and (negatively) by the growth of the labour supply: : foreign demand for exports (measured by weighted average of total imports of trade partners) = 0 y Z L Z 19

The test The neo-Lewis model is assumed to apply both before (B) and after (A) the crisis but with different intercepts. = + + + B i B i B i B i B i y Z L Z L = + + + A i A i A i A i A i y Z L Z L Subtracting: = + + + A i B i A i B i y ( ) ( ) Z L i Z i L i B i A i , 0, and 0. Z L I.e. the test is based on changes in growth rates, before versus after the crisis. 20

Data Latest release of EU KLEMS: 22 countries (EU plus Australia, Canada and US) Changes in growth rates, 2007-2015 compared to 2000-2007 Proxy for world demand: for i-th country, imports of its trading partners, weighted by i s exports to each or export-weighted imports (EWI). Source: NiGEM (NIESR). 21

Tests of neo-Lewis model Dependent variable: y (1) (2) 1.146** (0.474) -0.369* (0.200) (3) Z 1.270*** (0.395) -0.433*** (0.135) L Constant -1.745*** (0.377) 1.995 (1.231) 1.751 (1.024) Observations R-squared 22 0.168 22 0.285 22 0.513 Source: EU KLEMS, September 2017 release. Z is measured by NiGEM s EWI variable. 22

TFP The neo-Lewis model puts the stress on low rates of capital accumulation after the crisis. But in a growth accounting sense the collapse of TFP growth in the UK and elsewhere accounts for far more of the labour productivity decline than does capital shallowing. It s often argued nowadays that the TFP slowdown began before the crisis. Implication: the crisis had nothing to do with it and we should look to micro explanations (e.g. declining competition). 23

Little evidence of TFP slowdown before 2007 (Oulton, IPM, 2016) Growth of TFP in the market sector (A-K), % p.a. AUS AUT BEL CZE DNK 5.00 0.00 -5.00 ESP FIN FRA GER HUN 5.00 0.00 -5.00 IRL ITA JPN NLD SVN 5.00 0.00 -5.00 1970 1980 1990 20002007 1970 1980 1990 20002007 SWE UK USA 5.00 0.00 -5.00 1970 1980 1990 20002007 1970 1980 1990 20002007 1970 1980 1990 20002007 Actual Trend Mean Source: EU KLEMS. Note: Trend growth rate is that of HP-smoothed TFP level. Dashed lines denote country means of actual TFP growth rate. 24

Industry-level evidence for increasing returns/externalities A correlation across US manufacturing industries between productivity growth and output growth (Fabricant 1942). Also found for TFP and LP in UK manufacturing industries (Oulton and O Mahony, CUP, 1994). A tendency for TFP growth at the industry level to be higher when the whole economy is expanding faster. Hall, JPE, 1988; Caballero and Lyons, EER, 1990; Bartelsman et al., AER, 1994; Oulton, JIE, 1996 25

Increasing returns hypothesis Faster output growth causes faster TFP growth via increasing returns. Then a slowdown in GDP growth should lead to a slowdown in TFP growth. This can be tested on a panel of countries: 52 countries from the Penn Wold Table (since only 13 available from EU KLEMS). 26

Change in TFP growth versus change in GDP growth: 52 countries, 2007-2014 versus 2000-2007 27 Source: Penn World Table, version 9.0.

Externalities hypothesis vs Solow (52 countries) (a) Change in TFP growth vs change in GDP growth (b) Change in K/L growth vs change in TFP growth Dependent variable: Change in TFP growth Change in K/L growth Independent variables Change in GDP growth Change in capital growth Change in hours growth Change in TFP growth Constant (1) (2) (3) (4) 0.527*** (0.0803) 0.135 (0.151) -0.118 (0.152) 0.283 (0.194) 1.105*** (0.363) -0.281 (0.168) -1.259*** (0.221) -1.412*** (0.218) 52 0.514 52 0.018 52 0.018 52 0.058 N R-squared Source: Penn World Table, version 9.0. 28

Conclusions In Western economies foreign demand for exports has been constrained. This has led to slow growth of GDP. Slow growth of GDP has led to slow growth of TFP. In countries with inflexible labour markets unemployment has risen and remained high. But labour productivity growth, though reduced, has been higher than in the UK since the growth of labour input has been reduced. In countries like the UK with a very flexible labour market and rapid growth of labour input due to immigration, labour productivity growth has been lower than in other EU countries. Anti-austerity in any single country won t solve that country s problem, which is due to deficient export demand. Only coordinated expansion by all countries can work. In the UK case, controlling immigration can be part of the solution. 29

THE END 30

UK prospects as of the peak of the boom (beginning 2008) Inflation was on target, unemployment was low, productivity was growing strongly. Based on data available up to that time, and using a two-sector model (ICT vs everything else), I projected that UK labour productivity in the market sector would grow at 2.6% pa (Oulton, Ec. Mod., 2012 [2010]). Then something happened! 32

The UK puzzle has been much discussed and much reviewed Oulton, N. (2016). Prospects for UK growth in the aftermath of the financial crisis . In The UK Economy in the Long Expansion and its Aftermath (edited by J. Chadha et al., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Haldane, Andrew G. (2017). Productivity puzzles . https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/ speech/2017/productivity-puzzles. Tenreyro, Silvana (2018). The fall in productivity growth: causes and implications . Speech. www.bankofengland.co.uk/speeches. 33

Capital intensity in the UK market sector log scale, 1999=100 150 140 Capital intensity 130 120 110 100 199920002001200220032004200520062007200820092010201120122013 Note: Capital intensity is capital services (hybrid T rnqvist) per hour worked. R&D included. Source: Oulton and Wallis (2016). 34

OECD skills study Literacy: the ability to read and understand the label on a bottle of Aspirin. Numeracy: the ability to read the petrol gauge on a truck and calculate how many gallons remain. Findings 1. More than a quarter of adults aged 16-65 in England (and 10% of university graduates!) have low basic skills: they fail one or both of these tests. [GULP!] 2. Amongst migrants the skill level is lower than amongst the native born. (Migrants: those born abroad at least one of whose parents was also born abroad, 13% of the 16-65 population). Kuczera, Malgorzata, Simon Field and Hendrickje Catriona Windrisch (2016). Building skills for all: a review of England . OECD Skills Studies. Paris: OECD. 36

Mean growth of employment, % pa: up to and after the recession 1997Q1- 2008Q1 2010Q2- 2017Q2 UK-born 0.56 0.61 Foreign-born Total 6.01 1.09 5.73 1.39 After the end of the recession employment has grown faster than before it. Most of the growth in employment comes from the foreign-born, i.e. from immigration 37

Shares of the UK labour force by country of birth, % UK- born Foreign- born of EU Non-EU which: 1997Q1 92.7 7.3 2.4 4.9 2008Q1 87.4 12.6 4.4 8.2 2017Q2 82.2 17.8 7.4 10.3 Source: Office for National Statistics, Labour Force Survey. 38

The Lewis model Dual economy, two sectors: 1. Traditional (subsistence) sector. Low tech, low average productivity. 2. Capitalist sector. High tech, high average productivity. The capitalist sector can expand, as long as it can find a market for its products, by drawing labour from the subsistence sector. Labour is available in perfectly elastic supply from the subsistence sector at a wage equal to subsistence income plus a (small) margin. W Arthur Lewis (1954). Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour Manchester School. Douglas Gollin (2014). The Lewis model: a 60-year retrospective . Journal of Economic Perspectives. 39

The Lewis model (continued) During the Lewis growth process real wages are constant but GDP and profits grow. Eventually, the process comes to an end when surplus labour is exhausted. Thereafter any growth is neoclassical (like in the developed countries) and depends on technical progress. 40

Lewis model (capitalist sector) = 1 Y AK L The real wage is the marginal product of labour: (1 ) w AK L = = (1 ) Ak Migration from the subsistence sector keeps the real wage constant: 0 w A k = + = which implies that k A = A / 0 if 0 41

Lewis model (continued) So capital intensity in the capitalist sector is constant or declining. Consequently, y A k A = + = A = 0 i.e. productivity growth is zero. 42

How fast can GDP grow in the Lewis model? My interpretation: The growth of output and employment in the capitalist sector is determined by foreign demand (think sugar, cocoa, copper, export processing zones) 43

Comparing and reconciling Lewis and Solow Solow: the rising tide raises all boats Lewis: Only capitalists benefit (till surplus labour is exhausted) This is because: Solow: labour input is exogenous. Lewis: endogenous. Solow: no special role for exports Lewis: the growth of the capitalist sector and of GDP is constrained by foreign demand. 44

National income accounting = + + Real GDP(E) C I X pM = + + = = Real GDP(O) D I X Y : consumption of domestic output D 45

Household consumption Consumers maximise utility U which depends on the domestic good (D) and an imported good (M): s.t. the budget constraint D + pM = C. From the FOC = 1 0 1 U D M D M = p 1 whence = + p D M 46

The current account balance = 0 X pM whence = + p X M and (see previous slide) D = X i.e. domestic output of consumer goods and exports must grow at the same rate. 47

Foreign demand and the two regimes 0, 0 : foreign demand for : world income (exports cannot exceed foreign demand) X = d X Z d X Z X d X ( ) a good regime d : X X ( ) b bad re me = d : gi X X 48

Solutions (a) Good regime Same as Solow model: A = = = * * y : g k 1 (b)Bad regime = = D X Z and + by assumption Z g n so = + = y and Y Z g n Z L 49

How does this apply to the UK? We can think of the whole UK economy as the capitalist sector in the Lewis model. The rest of the world is the subsistence sector. The UK is exceptionally open to immigration, not just from the EU but from the rest of the world as well (58% of foreign-born workers are non-EU). It is more open than other EU economies because the UK labour market is very flexible : trade unions are weak, industry wage agreements are rare, and lack of formal qualifications is no barrier to employment in low-skill jobs. 50