Spina Bifida - A Neural Tube Birth Defect

Spina bifida is a neural tube birth defect causing neuromuscular dysfunction, with various types and factors contributing to its occurrence. The condition ranges from less severe anomalies to more complex forms, impacting neural and musculoskeletal functions. Early detection and management play crucial roles in addressing the challenges associated with spina bifida and enhancing quality of life for affected individuals.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Spina Bifida A.Mansoor rahman

Introduction Spina bifida is one type of neural tube birth defect causing neuromuscular dysfunction. The occurrence of spina bifida approached 1 in every 1000 pregnancies, making it the second most common birth defect after Down syndrome. The increased availability of maternal vitamin supplements, more accurate prenatal testing, and pregnancy termination options have greatly reduced the incidence of babies born with this diagnosis

Many factors may contribute to a baby being born with spina bifida. The presence of a genetic predisposition may be enhanced by numerous environmental influences. Low levels of maternal folic acid prior to conception have been implicated in several studies.

Definitions The terms myelomeningocele, meningomyelocele, spina bifida, spina bifida aperta, spina bifida cystica, spinal dysraphism, and myelodysplasia are all synonymous. Spina bifida is a spinal defect usually diagnosed at birth by the presence of an external sac on the infant s back . The sac contains meninges and spinal cord tissue protruding through a dorsal defect in the vertebrae. This defect may occur at any point along the spine, but is most commonly located in the lumbar region. The sac may be covered by a transparent membrane with neural tissue attached to its inner surface, or the sac may be open with the neural tissue exposed. The lateral borders of the sac have bony protrusions formed by the unfused neural arches of the vertebrae. The defect may be large, with many vertebrae involved, or it may be small, involving only one or two segments. The size of the lesion is not by itself predictive of the child s functional deficit.

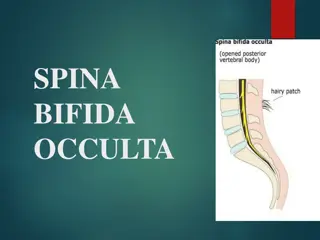

Several other congenital spinal defects are Spina bifida occulta, myelocele, and lipomeningocele are less severe anomalies associated with spina bifida. Spina bifida occulta is a condition involving nonfusion of the halves of the vertebral arches, but without disturbance of the underlying neural tissue. This lesion is most commonly located in the lumbar or sacral spine and is often an incidental finding when imaging is done for unrelated reasons.

Spina bifida occulta may be distinguished externally by a midline tuft of hair, with or without an area of pigmentation on the overlying skin. Between 21% and 26% of parents who have children with spina bifida cystica have been found to have an occulta defect. Otherwise, spina bifida occulta has only a 4.5% to 8% incidence in the general population. Neurologic and muscular dysfunction were previously thought to be absent in individuals with spina bifida occulta. However, a high rate of tethered cord, its associated neurologic problems, and especially urinary tract disorders in these individuals have been found.

A myelocele is a protruding sac containing meninges and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), but the spinal cord and nerve roots remain intact and in their normal positions. There are typically no motor or sensory deficits, hydrocephalus, or other central nervous system (CNS) problems associated with a myelocele. Lipomeningocele is a superficial fatty mass in the low lumbar or sacral region of the spinal cord. Significant neurologic deficits and hydrocephalus are not expected in patients with a lipomeningocele. However, a high incidence of bowel and bladder dysfunction resulting from a tethered spinal cord has been noted in this population as well as subtle changes in distal leg and foot function, which is usually seen later in childhood or early adolescence, especially after a growth spurt.

Embryology Spina bifida cystica, one of several neural tube defects, occurs early in the embryologic development of the CNS. Cells of the neural plate, which forms by day 18 of gestation, differentiate to create the neural tube and neural crest. The neural crest becomes the peripheral nervous system, including the cranial nerves, spinal nerves, autonomic nerves, and ganglia. The neural tube, which becomes the CNS, the brain, and the spinal cord, is open at both the cranial and caudal ends. Over a period of 2 to 4 days, the cranial end begins to close and this process is completed on approximately the 24th day of gestation.14 Failure to close results in anencephaly, a fatal condition. The caudal end of the neural tube closes on approximately day 26 of gestation. Failure of the neural tube to close at any point along the caudal border initiates the defect of spina bifida cystica or myelomeningocele.

Common clinical signs of spina bifida include an absence of motor and sensory function (usually bilateral) below the level of the spinal defect and loss of neural control of bowel and bladder function. Unilateral motor and sensory loss has been seen and the pattern of loss may also be asymmetric, with a higher motor or sensory level on one side compared with the other. The functional deficits may be partial or complete, but they are almost always permanent.

Hydrocephalus abnormalities that are closely associated with spina bifida. Hydrocephalus is an abnormal accumulation of CSF in the cranial vault. and the Arnold Chiari malformation are CNS In individuals without spina bifida, hydrocephalus may be caused by overproduction of CSF, a failure in absorption of CSF fluid, or an obstruction in the normal flow of CSF through the brain structures and spinal cord. Obstruction by the Arnold Chiari malformation is considered to be the primary cause of hydrocephalus in most children with spina bifida. This malformation, also known as the Chiari II malformation, is a deformity of the cerebellum, medulla, and cervical spinal cord. The posterior cerebellum is herniated downward through the foramen magnum, with brainstem structures displaced in a caudal direction. The CSF released from the fourth ventricle is obstructed by these abnormally situated structures, and the flow through the foramen magnum is disrupted.

Sbymptoms Associated with Chiari II malformation Stridor especially with inspiration Apanea when crying, or at night Gastroesophageal reflux Paralysis of vocal cords Swallowing difficulty Bronchial aspiration Tongue fasciculations Facial palsy Poor feeding Ataxia Hypotonia Upper extremity weakness Seizures Abnormal extraocular movements Nystagmus

Physical therapy for the infant with spina bifida Manual Muscle Testing; Manual muscle testing should be performed before back surgery whenever possible. Testing may be repeated approximately 10 days after surgery,then at 6 months, and yearly. Palpation and observation of the muscle during a preoperative assessment of the active movement in the lower extremities. Stimulation of the infant to elicit movement and palpation during manual muscle testing

The principles for muscle testing in the infant population are much the same as those for older patients, of course with the exception that the baby cannot follow directions. Gentle resistance to movement at one part of the leg may help increase the strength of a movement at a distal part of the limb, and allowing movement to occur at only one joint at a time will assist in a more accurate interpretation. For example, holding firmly onto the hip and knee in either partial flexion or extension to prevent movement at those joints will enable the therapist to observe and detect weak ankle motion that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Range-of-motion Assessment Preliminary assessment of range of motion (ROM) of the lower extremities can also be performed prior to back closure. Typical, full-term neonates have flexion contractures of up to 30 degrees at the hips and 10 to 20 degrees at the knees, and ankle dorsiflexion of up to 40 or 50 degrees. There are several common joint limitations seen in the neonate with spina bifida. Extreme tightness of the hip flexors may be evident in the child with a motor level at L-2 to L-3 or L-3 to L-4 owing to the presence of a strong iliopsoas with no opposing force offered from absent hip extensors. Hamstrings, which exert a secondary hip extension force, may also be absent or weak, in which case hyperextension of the knees may also be present along with the hip flexion. Adductor tightness may be seen as a result of innervation of the adductors and absent antagonists, the gluteus medius.

Extreme dorsiflexion at the ankle is another common contracture seen at birth. The child with an L-5 innervation has strong ankle dorsiflexion, provided by the anterior tibialis and toe extensors, but weak or absent toe flexors and lack of plantarflexion from the gastrocnemius/soleus group. Serial taping or splinting of the ankle to bring it down to 90 degrees, and in addition, gentle passive exercise often helps reduce this deformity within a short period of time.

Postoperative Physical Therapy PT should develop a comprehensive and appropriate program for the infant who has undergone back closure and shunt insertion, consideration must be given to both the neurologic and orthopedic findings. Communication with Team Members and Parents All persons working with the infant should know and understand each other s findings so contradiction does not occur. Information should be provided to the family by the appropriate personnel in an open and honest manner, but also in a sensitive manner. PT should be to reflect a positive and caring attitude during treatment sessions. This approach can help to normalize the involvement of family members with their infant. Teaching portions of a home program to the family can begin immediately. This is a constructive way for the therapist to begin building a relationship with the family.

Range-of-motion Exercises Daily sessions for lower extremity ROM exercises can begin after back closure and taught to parents as soon as feasible. ROM exercises are performed gently with the therapist s hands placed close to the joint being moved, to use a short lever arm, which prevents stress to soft tissue and joint structures. Several repetitions of each pattern, holding the joint briefly at the end of the range, can maintain and even increase ROM, where there is a mild or moderate limitation. If severe limitations exist, exercise at that joint may require some additional time and repetition. But aggressive stretching should be avoided, regardless of the severity of the contracture.

Positioning and Handling The baby may be limited to prone or side-lying. Handling and carrying strategies can be practiced by the therapist and then recommended to the parents. The therapist or family member can hold the child prone over their lap, rocking or swaying slowly side to side. This position is restful for the parent and provides novel movement for the infant. If the supine and sitting positions are contraindicated, parents may gently cradle the infant prone across one forearm. These few position options will provide a small repertoire of acceptable handling strategies. These positions are also safe for the infant, who needs time to recover and who may not respond well to more aggressive movement and handling.

Sensory Assessment By mapping this sensory information, along with the results of muscle testing, the level of the spinal lesion can be more accurately established. This assessment will also identify the areas of intact sensation on the baby s trunk and legs, so stimulation at those spots will make the baby move. Strokes at the plantar surface of the foot, make the child react. This technique is successful only when the infant has intact sensation at the sacral nerve roots. Infants with spina bifida have a higher level of sensory deficit and need to be stimulated on the thigh or somewhere on the trunk. Using a gentle touch, caress, or tickle, a family member can map out areas of responsiveness. Insensitive areas of the lower extremities will require protection because the child will be unaware of injury to these areas of denervation. For example, families must always test the temperature of bath water prior to immersing the child.

Developmental Issues It is apparent that a significant number of children with spina bifida exhibit CNS deficits, and for some, the effect of these deficits can be more detrimental to the child s function than their lower extremity paralysis. The CNS deficits can have a major impact on the child s acquisition of gross motor, fine motor, perceptual motor, and cognitive skills.

Goals of Neurosurgical Care for Patients with Spina Bifida Coordinate early care prior to back closure. Assess location and size of the back defect. Perform closure of the back defect. Assess extent of lower extremity paralysis. Assess and treat hydrocephalus. Monitor function of ventricular shunt. Monitor patient for acute and chronic CNS abnormalities. Monitor the patient for CNS deterioration, tethered cord, and hydromyelia.. Provide support/collaboration to clinical team.

Goals of Orthopedic Care for Patients with Spina Bifida Provide pertinent information to family: current and projected issues. Prevent fixed joint contractures. Correct musculoskeletal deformities. Prevent skin breakdown from structural malalignment. Provide resources to achieve best mobility. Monitor for scoliosis. Monitor the patient for CNS deterioration, tethered cord .. Provide support/collaboration to clinical team.

Handling strategies for parents The developmental delays that may be seen in some children, especially the possible difficulty in developing control of the head and upper body. Parents should not permit the baby to be held or positioned with the head at severe angles. The presence of hypotonus will influence the acquisition of antigravity head control in all directions, and we must alert caregivers to avoid allowing the overstretching of neck muscles and other soft tissue structures

Goals of Physical Therapy for Patients with Spina Bifida Establish preliminary motor level by manual muscle test. Provide medical team with accurate information regarding lower limb movement. Perform periodic manual muscle testing for comparison purposes. Provide instruction to family for a long-term home program to prevent lower extremity deformity. Provide home program instruction to facilitate motor development as close to chronologic age as is possible. Assist in determining appropriate orthosis. Facilitate mobility program for ambulation and wheelchair use, where indicated. Provide information regarding the patient s neurologic function. Monitor the patient for CNS deterioration, tethered cord, and hydromyelia. Provide support/collaboration to clinical team.

Signs and Symptoms of Shunt Malfunction Infants: Bulging fontanelle Vomiting Change in appetite Sunset sign of eyes Edema, redness along shunt tract Toddlers: Vomiting Irritability Headaches Edema, redness along shunt tract

School-aged Children: Headaches Lethargy Irritability Edema, redness along shunt tract Handwriting changes High-pitched cry Seizures Rapid growth of head circumference Thinning of skin over scalp Nystagmus Eye squint Vomiting Decreased school performance Personality changes Memory change