Significant Figures in Electronic Instrumentation

Everyday measurements often require significant figures to account for precision and accuracy. Learn about the importance of significant figures in electronic instrumentation, how to interpret them, and why they are crucial for precise measurements in scientific fields such as physics.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Topic Introduction to Electronic Instrumentation and Measurements Presented by Dr. S. D. More Assistant Professor & Head Department of Physics Deogiri College, Aurangabad

B. Sc. First Year (Instrumentation Science) Paper II: Instrumentation - II

1. Introduction to Electronic Instrumentation and Measurements

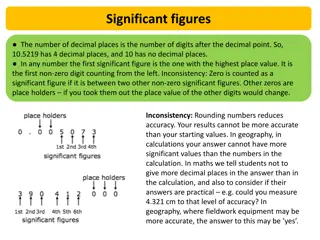

Much of our everyday experience deals with exact numbers of things i. e. 6 stamps, 7.50 dollars and 7 people. These items can be counted and an exact numerical representation provide' all figures are significant in such cases. But in other situations, you may take measurement; that are subject to errors. For example, 1) you might measure the height of a person as 67, 68, or 69 in, depending on how straight the person stands.

2) How many people do you know who own a perfectly accurate watch that never needs to be reset"! None! These flaws are implicitly resolved when we apply the concept of significant measurements. figures to the This concept demands that we impute no more precision or accuracy calculation than the natural physical reality of the situation permits. to a measurement or The counting numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) are always significant.

Zero is significant only if it is used to indicate exactly zero, or a truly null case. Zero is not significant if it is used merely as a place holder to make the numbers look nicer on the printed page. For example, if "0.60" is properly written, then it means exactly 6/10 not "approximately 0.6 . The zero used here in the hundredth place is significant. If the number is written "0.6," then we may assume that it means 6/10 plus or minus some amount of either error or uncertainty.

When we use numbers to indicate a quantity, the concept of significant figures becomes important. For example, "16 gal" has two significant figures but can reasonably be taken to mean that the quantity of liquid is somewhere between 15 and 17 gal. But if our liquid measuring device is better, then we might write "16.0 gal" to indicate precisely 16 gal pIus or minus a very small error. Perhaps the real value is between 15.9 and 16.1 gal.

Consider a pressure gauge that is guaranteed to an accuracy of 5%. A reading of "100 torr" has three figures, meaning that the actual pressure is between [100 - 5%] and [100 + 5%], or 95 to 105 torr (two significant figures). Consider experiment uses a digital voltmeter to measure an electrical potential difference of exactly 15 V. The instrument reads from 00.00 to 19.99 V, with an accuracy of 1%. In addition, digital voltmeters typically have a 1-digit error in the least significant position due to their design;. This problem is called last digit bobble. a practical measurement situation. An

For the digital voltmeter in question, 19.99 Most significant digit Least significant digit The "last digit bobble" problem means that a reading of 15.00 V could represent any value between 15.00 - 00.01 (i.e. 14.99) V and 15.00 + 00.01 (i.re. 15.01) V. In addition, the error of 1% means that the actual voltage could be (15 x 0.01) = 0.15 V. Thus, the actual voltage could be from (15.00 - 0.15) V to (15.00 + 0.15) V, or a range of +14.84 to +15.16 V.

If both errors are minus, Reading: 15.00 V 0.01 V 0.15 V 14.84 V (worst case) or, if both errors are positive, Reading: 15.00 V +0.15 V +0.01 V 5.16 V (worst case)

Significant calculations. figure errors are propagated in A rule to remember is that the number of significant figures is not improved by combining the numbers with other numbers. For example, multiplying a significant digit by a non- significant digit yields a result that has at least one non-significant digit. Often the number of significant figures decreases in calculation. Significant figure rules were perhaps a little easier to understand and use in the days when scientists and engineers calculated on slide rules.

Those tools were limited to two or three digits, so one was less tempted to write down a very long number. But in this age of 10-digit scientific pocket calculators, and the nearly universal distribution of personal computers, the distinction often gets lost. Consider a simple electrical problem as an example. One expression of Ohm's law states that the current I flowing in a circuit is the quotient of the voltage V and the resistance R. Suppose that 10 V is applied to a 3 resistance.

According to pocket scientific calculator, the current is 10 V/3 = 3.333333333 A. Does anyone really think that their ordinary, laboratory ammeter can measure to within 10-9A (i.e., 3.33 nA)? In most cases we would be exaggerating to claim more than 3.33 or 3.333 A (at most) with very high quality meters with recent calibration stickers on them! Indeed, on most lower-quality instruments, "3" or "3.3"would be a more reasonable statement of the current reading.

Being mindful of significant figures is a key factor in making good electronic maintaining the integrity and credibility of the measurement system. measurements and

Scientific Notation Scientific notation is a simple arithmetic shorthand that allows one to deal with very large or very small numbers using only a few digits between 1 and 10 and using powers-of-10 exponents. The form of a number in scientific notation is

For example, if the age of a college physics professor is 47 years, it could be written Prof's age = 4.7 x 101years

Standard values in powers of 10 notation along with respective Prefix