Pandemic Economics Through Game Theory

Exploring the application of game theory in pandemic economics, this chapter delves into the strategic interactions among individuals, policymakers, and the spread of disease. It discusses the impact of cooperation, defection, and policy interventions on social outcomes during a pandemic, shedding light on decision-making dynamics and incentives in such crises.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Game Theory Game Theory PANDEMIC ECONOMICS PANDEMIC ECONOMICS CHAPTER 14 CHAPTER 14 1 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

1. A Game of Survival 2. Game Theory and Pandemic Outcomes 3. Principles of Game Theory 4. Bargaining Game Topics Topics 5. Donor-Recipient Game 6. Public Good Game 7. Game of Risk Perception and Strategic Choice 2 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Learning Objectives Learning Objectives After reading this chapter, you will be able to: After reading this chapter, you will be able to: LO1 Apply the game theory perspective to pandemic applications. LO2 Explain why individual decisions may not lead to optimal social outcomes. LO3 Discuss the principles of both strategic form and extensive form games. LO4 Determine whether sheltering-in-place orders impact the decision to cooperate. LO5 Assess the reasons that individuals may cooperate and slow the spread of disease. LO6 Determine the conditions in which individuals will choose vaccinations. LO7 Address why risk perception and policy interventions influence human behavior. 3 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 10

During a pandemic, we may view individuals as participating in a game of strategic interaction. In the game, members of a target population serve as players and payoffs exist. 1. A Game of 1. A Game of Survival Survival Policymakers attempt to minimize the spread of disease. The disease attempts to maximize infections. Individuals attempt to minimize the risk of infection while maintaining economic opportunity. 4 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Cooperation or Defection Cooperation or Defection Policy interventions may lead to cooperation by slowing the spread of disease but involve costs such as economic losses, isolation, and loneliness. For individuals, defecting from the position of isolation, loneliness, and cooperative behavior brings immediate benefits, including interaction and social connection. But defection worsens the position of the population by increasing infections. 5 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Social Outcomes Social Outcomes An incentive exists for individuals to choose a path that does not produce the optimal social outcome. As a result, the decision to abide by policy interventions exists as a multiplayer version of the game. Individuals may cooperate, experience personal costs, and help society, or defect, reduce personal costs, and impose external costs on the population. 6 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Game Theory Game Theory The point is that, during a pandemic, individuals face a series of strategic decisions in unfamiliar situations, including sheltering-in- place and social distancing. Because game theory, the study of strategic choice, addresses individual decision making and social outcomes, it offers a method to analyze human behavior during a pandemic. 7 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Game theory provides a framework for modelling strategic interaction between decision makers, which may be considered a game with rules, strategies, and payoffs: 2. Game 2. Game Theory and Theory and Pandemic Pandemic Outcomes Outcomes Rules: instructions that dictate choices and outcomes Strategies: options for players in which the outcome depends on both the player s choice and the choices of other participants Payoffs: values assigned to possible outcomes of a game, including monetary, social, and psychological values 8 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Strategic Interaction Strategic Interaction Game theory addresses the outcomes of strategic interaction, focusing on incentives and preferences. Traditional games often assume perfect information and mutual interdependence, the idea that the decisions of one player depend on the decisions of others. But in a pandemic, incomplete information may exist with disease characteristics, transmission, and potential outcomes. 9 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Social Dilemma Social Dilemma In the presence of a social dilemma, game theory serves as a useful tool. A social dilemma exists when non-cooperative payoffs exceed cooperative payoffs. That is, individuals receive higher payoffs when they defect from a decision that leads to greater social benefits, no matter the behavior of others. But if most people do not cooperate, everyone is worse off. In contrast, if full cooperation occurs, everyone is better off. 10 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Equilibrium occurs when individuals cannot increase their payoffs by altering their strategy. 3. Principles 3. Principles of Game of Game Theory Theory A game approximates reality and includes interaction. Actions of cooperation or defection approximate choices that exist in a more complex plane. 11 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Language of Game Theory Language of Game Theory When a choice leads to a higher payoff, a dominant strategyexists. This is a strategic decision that is optimal regardless of the decision of the rival. But the outcome of a game may be a non-cooperative solution, when players do not collaborate, each pursuing their own self-interest. A Nash equilibriumserves as an outcome in which players may not improve their position with different choices. Two common approaches are strategic form gamesand extensive form games. 12 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Strategic Form Games Strategic Form Games Strategic form games occur when players choose strategies without knowing the strategies of other players. This form is common for simultaneous games, when players make their strategic decisions at the same time, as opposed to sequential games, when players make their decisions in turn. 13 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Simultaneous Simultaneous Move Game Move Game 14 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Suppose a player, Yellen, decides whether to make 1 or 2 units of output. At the same time, another player, Powell, faces the same decision. If Yellen decides to make 2 units, Powell maximizes his payoff by making 2 units. If Yellen decides to make 1 unit, Powell maximizes his payoff by making 2 units. How to Play How to Play the the Simultaneous Simultaneous Move Game Move Game Therefore, regardless of the actions of Yellen, Powell s dominant strategy is to make 2 units. Yellen also has a dominant strategy of making 2 units. With this choice, she maximizes her payoff, regardless of the actions of Powell. A cooperative solutionoccurs in the upper left-hand box when each player agrees to produce 1 unit and receive a payoff of $36. A cooperative solution is an outcome that occurs when each player collaborates with the other. But each player has a dominant strategy of producing 2 units. Therefore, a non-cooperative solution serves as the Nash equilibrium. In the lower right-hand box, each player receives a payoff of $32. 15 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Prisoners Prisoner s Dilemma Dilemma 16 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

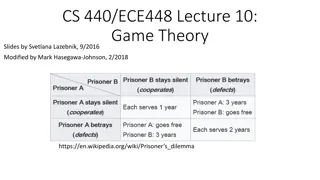

Suppose two suspects, FJ and JJ, are accused of a crime. The police take them to the station for questioning but place them in different rooms. How to Play How to Play the Prisoner s the Prisoner s Dilemma Dilemma Game Game They cannot collaborate. The police have enough evidence to convict them of resisting arrest, a lesser crime, but suspect them of a more serious crime. Each player must decide whether to provide evidence. 17 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Payoffs for Prisoners Dilemma Payoffs for Prisoner s Dilemma The payoffs are established as follows: if a suspect provides evidence but the other does not, the player who provides evidence goes free. The player who does not provide evidence receives a 14-year sentence. If they both provide evidence, they each receive a 7-year sentence (lower right-hand box). If neither provides evidence, they each receive a 1-month sentence for resisting arrest (upper left-hand box). From the perspective of the suspects, what is the best outcome? Clearly, the answer is to provide no evidence. This choice leads to the shortest collective sentencing. But this choice requires collaboration, which the suspects cannot provide. 18 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Dominant Strategy Dominant Strategy Consider the actions of FJ, who decides whether to provide evidence, but has no control over JJ s decision. FJ knows that JJ has two choices. One, if JJ presents no evidence, FJ should provide evidence and go free. Two, if JJ provides evidence, FJ should provide evidence and receive a 7-year sentence rather than a 14-year sentence. A dominant strategy exists: provide evidence. Because this is a symmetric game, JJ has the same dominant strategy. The result is a Nash equilibrium. Both players follow their dominant strategy in a non-cooperative solution (lower right-hand box). Taken together, they would be better off cooperating and withholding evidence. 19 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Extensive Form Games Extensive Form Games Extensive form games describe the setting with a game tree, a diagram of player choices. At the end of each branch, payoffs exist. Because this form characterizes choices at different moments, it involves sequential games. Players know their previous choices and observe the choices of other players. 20 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Sequential Move Games Sequential Move Games In sequential move games, arrows represent player decisions. The initial player makes a choice, and the other player responds. Payoffs occur at the end of the game. Economists use sequential move games to study many topics, including altruism. 21 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Ultimatum Ultimatum 22 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

The first player, Alpha, receives $20 and may give some (call it X) to Beta. Beta must then decide whether to accept or reject Alpha s offer. If Beta accepts, Beta keeps X and Alpha keeps the rest (call it Y). How to Play How to Play Ultimatum Ultimatum If Beta rejects, neither keeps any money. An equitable offer, for example, would equal $10. If Beta accepts, X = $10 and Y = $10. Economists have found that in repeated games the Betas normally reject offers below $3, citing unfairness. 23 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Dictator Dictator As an extension to Ultimatum, Dictator simplifies the competing factors of altruism and self-interest. While money is divided between two anonymous players, Alpha makes the only decision. Beta keeps Alpha s offer. The original version of the game provides Alpha with two options: (a) keep $18 and give Beta $2 or (b) keep $10 and give Beta $10. What is the typical result? The results demonstrate that most people, when in the position of Alpha, choose to split the money evenly. 24 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

During sheltering-in-place interventions, individuals isolate in their residences. 4. Bargaining 4. Bargaining What is the relationship between observable worker characteristics and loneliness? Game Game In a labor market setting, what is the relationship between sheltering-in-place orders, loneliness, and cooperative behavior? 25 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Types of Experiments Types of Experiments Experiment Subjects Location Awareness Conventional lab Standard Laboratory Awareness exists Artefactual field Non-standard Laboratory Awareness exists Framed field Non-standard Natural environment Awareness exists Natural field Non-standard Natural environment No awareness 26 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Design Flow Design Flow For the bargaining game, the design flow of Babin et al. (2020) begins with the establishment of online participants. They consent to participate and then proceed to the reporting phase. In the reporting phase, they answer questions on psychometric scales which determine both their degrees of loneliness and willingness to cooperate. They also express whether they are under a sheltering-in-place order. The participants then begin the bargaining phase, in which they play both a stag hunt gameand a prisoner s dilemma, randomized to eliminate potential bias in the results. 27 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Stag Hunt Game Stag Hunt Game In the original version, players decide whether to hunt a stag or a hare. The stag provides a higher payoff than the hare. To succeed in hunting a stag, the players must cooperate. But individual action may lead to the capture of a hare. In this game, the highest value entails mutual cooperation. 28 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Equilibrium Outcomes Equilibrium Outcomes In Babin et al. (2020), actions are framed as group projects. Participants may cooperate or work alone. The stag hunt framework differs slightly from the framework of Prisoner s Dilemma. In the latter, the only pure Nash equilibrium is when both players defect, even though cooperation by both players is efficient. But the stag hunt game has two predictions (Nash equilibria): a bad one, which is sub-optimal yet safer for each player, and a good one, which is Pareto efficient but risky. 29 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Working Alone Working Alone When will participants work alone? Babin et al. (2020) find that, for participants in the stag hunt game, as sheltering-in-place orders extend into subsequent waves, less cooperation exists until the orders are lifted and cooperation rebounds. For participants in the prisoner s dilemma game, cooperation increases as sheltering-in-place orders extend into subsequent waves. Workers under sheltering-in-place orders cooperate less often in the stag hunt bargaining framework when compared to the prisoner s dilemma. 30 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Karlsson and Rowlett (2020) model a population in which individuals evaluate the merits of behavioral adjustments that slow the spread of disease. Individuals face a choice: either mitigate the spread of disease or not. 5. Donor 5. Donor- - Recipient Recipient Game Game When they mitigate the spread of disease, they must change their behavior, leading to a disease dilemma, similar in form to the prisoner s dilemma. They either cooperate with others in the population and minimize the spread of disease or defect and not minimize the spread of disease. This form of the game is called a donor-recipient game when players donate resources to help others. 31 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Decision Decision Matrix and Matrix and Payoffs Payoffs 32 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Playing the Game Playing the Game Suppose two players, Austin and Claudia, choose to either cooperate with others or defect from the group. Cooperating and mitigating the spread of disease takes the form of social distancing, wearing a mask, and/or sheltering-in-place. Defecting and not mitigating the spread of disease means not changing behavior. Four potential outcomes exist: A and C both defect; A cooperates and C defects; A defects and C cooperates; and A and C both cooperate. 33 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

With many infectious diseases, the choice to obtain a vaccination impacts disease control A public good game of vaccination provides an important difference: payoffs vary according to age group. In a vaccination game, Chapman et al. (2012) consider the case of influenza, noting that young people are responsible for most of the transmission, while the elderly experience higher levels of morbidity and mortality. From a social perspective, the optimal strategy is for younger people to assume an important role in the process of vaccination to protect older people. This strategy exists despite the fact that younger people receive a lower personal benefit than older people. 6. Public 6. Public Good Game Good Game 34 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Rules and Payoffs Rules and Payoffs To reduce the risk of infection, individuals may choose to receive a vaccination. If they receive the vaccination, they experience a cost. In the laboratory experiment, individuals assume the cost by paying points. In addition, if they become infected, they lose points. For some individuals, the choice of nonvaccination leads to a higher expected payoff. 35 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Equilibrium Outcomes Equilibrium Outcomes In this game, Chapman et al. (2012) analyze two types of equilibria. The Nash equilibrium predicts the outcome if participants act in a self- interested manner. It is defined as the number of participants in the young and elderly groups that choose vaccination to maximize individual payoff, beyond which no incentive exists for further vaccination. A utilitarian equilibrium, in contrast, represents the group-oriented solution. It is defined as the number of participants in the young and elderly age groups that choose vaccination to maximize the group payoff. 36 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

During a pandemic, both the perception of risk and intervention policies influence human behavior. 7. Game of 7. Game of When control measures relax but infections exist, individuals may re-introduce defensive measures. Risk Risk That is, in order to reduce the risk of infection, they may change their behavior. Perception Perception and Strategic and Strategic Choice Choice Depending on the level of infections, an imitation process may spread throughout the community. From the individual perspective, if the perceived risk of infection is large, a choice of fewer contacts will reduce the spread of disease. 37 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Model Framework Model Framework In the Poletti et al. (2012) framework, the link between uncoordinated responses and risk perception serves as an important factor in modeling disease transmission. Changes in risky behavior are a function of risk perception of the disease. From the perspective of human activity, the area of interest is the identification of the factors that determine both risk perception and behavioral changes. From the perspective of the disease, these factors lead to changes in the dynamics of infection. A larger perception or risk and more defensive actions may slow the spread of disease. 38 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Game Theory Approach Game Theory Approach A game theory approach establishes a model of susceptible individuals, focusing on two relationships: (1) behavioral changes that result from the perceived risk of infection and (2) the impact of different levels of infection on risk perception. By taking appropriate defensive measures such as wearing face masks, limiting travel, and avoiding crowded spaces, individuals may reduce the risk of exposure. The model captures the dynamics of defensive behavior. Individual behavior corresponds to strategies with expected payoffs. Behavior is a function of the perceived risk of infection. The framework models this relationship using imitation dynamicswhen each player observes the actions of other players and decides whether or not to imitate their strategy. If the perceived gain is sufficiently large, imitation occurs. If not, imitation does not occur. 39 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

Learning Learning Learning exists as part of the game. Through personal encounters, individuals assess the strategies of others by comparing payoffs. If their payoff increases with the adoption of another strategy, change occurs. The game theory approach therefore captures two processes: dynamics of disease transmission and dynamics of imitation, which differ with respect to a focus on contacts and behavior, respectively. 40 PANDEMIC ECONOMICS 14

undefined

undefined