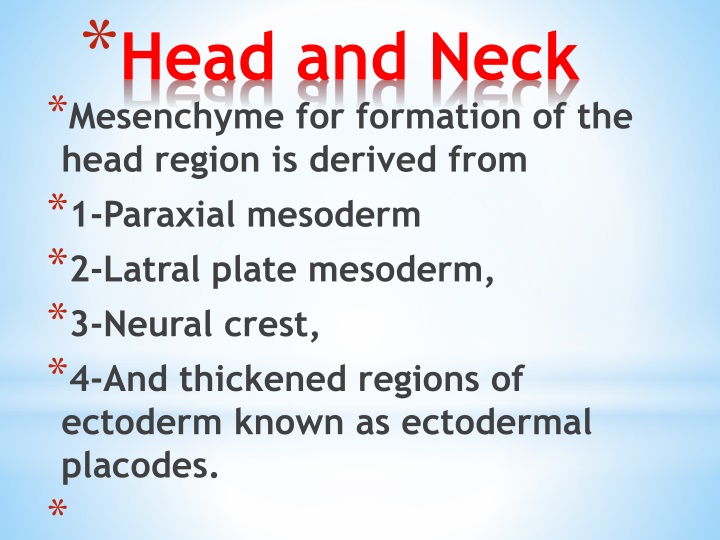

Development of Head and Neck Mesenchyme in Embryonic Formation

The formation of the head and neck region in embryonic development involves mesenchyme derived from paraxial mesoderm, lateral plate mesoderm, neural crest, and ectodermal placodes. Paraxial mesoderm contributes to brain case and muscle formation, while lateral plate mesoderm forms laryngeal cartilages. Neural crest cells originate in the neuroectoderm and contribute to skeletal structures. Pharyngeal arches play a crucial role, forming distinct structures essential for the head and face. Mesenchyme from neural crest, lateral plate mesoderm, and paraxial mesoderm shapes skeletal structures in the head and face. The development of pharyngeal arches involves mesenchymal tissue bars and pouches.

Uploaded on Oct 08, 2024 | 3 Views

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

*Head and Neck *Mesenchyme for formation of the head region is derived from *1-Paraxial mesoderm *2-Latral plate mesoderm, *3-Neural crest, *4-And thickened regions of ectoderm known as ectodermal placodes. *

*Paraxial mesoderm *1-(Somites and Somitomeres) forms the floor of the brain case and a small portion of the occipital region . *2-All voluntary muscles of the craniofacial region *3-Dermis . *4-Connective tissues in the dorsal region of the head . *5- Meninges caudal to the prosencephalon.

*Lateral plate mesoderm: *Forms the laryngeal cartilages (arytenoid and cricoid) and connective tissue in this region. *Neural crest cells originate in the *1-neuroectoderm of forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain regions and migrate ventrally into the pharyngeal arches In these locations, they form midfacial and pharyngeal arch skeletal structures (Fig. 16.1)

*and all other tissues in these regions, including 2-Cartilage, 3-Bone, 4-Dentin, 5-Tendon, 6-Dermis, 7- Pia and arachnoid, 8-Sensory neurons, 9-And glandular stroma..

* . Cells together neurons of the fifth, seventh, ninth, and 10th cranial sensory ganglia. 1975 *The most typical development of the head and neck is formed by the pharyngeal or branchial arches. These arches appear in the fourth and fifth weeks of development and contribute to external appearance (Table 16.1 and Fig. 16.3). from ectodermal neural placodes, crest, with form feature in the characteristic the embryo of

Skeletal structures of the head and face. Mesenchyme for these structures is derived from neural crest (blue), lateral plate mesoderm (yellow), and paraxial mesoderm (somites and somitomeres) (red).

*Pharygeal arch ,Initially, they consist of bars of mesenchymal tissue separated by deep clefts known as pharyngeal clefts . Simultaneously,with development of the arches and clefts, a number of outpocketings, the pharyngeal pouches

*PHARYNGEAL ARCHES *Each pharyngeal arch consists of a core of mesenchymal tissue covered on the outside by surface ectoderm and on the inside by epithelium of endodermal origin (Fig. 16.6). In addition to mesenchyme derived from paraxial and lateral plate mesoderm, the core of each arch receives substantial numbers of neural crest cells, which migrate into the arches to contribute to skeletal components of the face. The original mesoderm of the arches gives rise to the musculature of the face and neck.

*Thus, characterized by its own muscular components. The muscular components of each arch have their own cranial nerve, and wherever the muscle cells migrate, they carry component with them (Figs. 16.6 and 16.7). In addition, each arch has its own arterial component . (Derivatives of the pharyngeal arches and their nerve supply are summarized in Table 16.1, p. each pharyngeal arch is their nerve

*First Pharyngeal Arch *The first pharyngeal arch consists of a *1-Dorsal portion, the maxillary process, which extends forward beneath the region of the eye, and a *2-Ventral portion, the mandibular process, which contains Meckel's cartilage (Figs. 16.5 and 16.8A). During further development, Meckel's cartilage disappears except for two small portions at its dorsal end that persist and form the incus and malleus (Figs. 16.8B and 16.9). *Mesenchyme of the maxillary process gives rise to the premaxilla, maxilla, zygomatic bone, and part of the temporal bone through membranous ossification (Fig. 16.8B).

*The mandible is also formed by membranous ossification mesenchymal tissue surrounding Meckel's cartilage. In addition, the first arch contributes to formation of the bones of the middle ear (see Chapter 18 of

*Musculature of the first pharyngeal arch includes the muscles of *1-Mastication (temporalis, masseter, and pterygoids), *2-Anterior belly of the digastric, *3-Mylohyoid, *4-Tensor tympani, and *5-Tensor palatini. The nerve supply to the muscles of the first arch is provided by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (Fig. 16.7). Since mesenchyme from the first arch also contributes to the dermis of the face, sensory supply to the skin of the face is provided by ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve.

*Second Pharyngeal Arch *The cartilage of the second or hyoid arch (Reichert's cartilage) (Fig. 16.8B) gives rise to *1-The stapes, *2-Styloid process of the temporal bone, *3-Stylohyoid ligament, *4-And ventrally, the lesser horn and *5-Upper part of the body of the hyoid bone (Fig. 16.9). Muscles of the hyoid arch are the *1-Stapedius, 2-Stylohyoid, 3-Posterior belly of the digastric, 4-Auricular, and expression. *The facial nerve, the nerve of the second arch, supplies all of these muscles 5-Muscles of facial

*Third Pharyngeal Arch *The cartilage of the third pharyngeal arch produces the *1-lower part of the body and *2-greater horn of the hyoid bone . *The musculature is limited to the stylopharyngeus muscles. *These muscles are innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve, the nerve of the third arch (Fig. 16.7).

*Fourth and Sixth Pharyngeal Arches *Cartilaginous components of the fourth and sixth pharyngeal arches fuse to form the *1-Thyroid, 2-Cricoid, 3-Arytenoid, *4- Corniculate, and 5-Cuneiform cartilages of the larynx (Fig. 16.9). Muscles of the fourth arch (cricothyroid, levator palatini, and constrictors of the pharynx) are innervated by the superior laryngeal branch of the vagus, the nerve of the fourth arch. Intrinsic muscles of the larynx are supplied by the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus, the nerve of the sixth arch.

PHARYNGEAL POUCHES The human embryo has four pairs of pharyngeal pouches; the fifth is rudimentary .Since the epithelial endodermal lining of the pouches gives rise to a number of important organs, the fate of each pouch is discussed separately. Derivatives of the pharyngeal summarized in Table 16.2, p. 273. pouches are

*First Pharyngeal Pouch *The first pharyngeal pouch forms a stalk-like diverticulum, the tubotympanic recess, which comes in contact with the epithelial lining of the first pharyngeal cleft, the future external auditory meatus (Fig. 16.10). The distal portion of the diverticulum widens into a sac-like structure, the primitive tympanic or middle ear P.272 cavity, and the proximal part remains narrow, forming the auditory (eustachian) tube. The lining of the tympanic cavity later aids in formation of the tympanic membrane or eardrum (see Chapter 17).

Second Pharyngeal Pouch The epithelial lining of the second pharyngeal pouch proliferates and forms buds that penetrate into the surrounding mesenchyme. The buds are secondarily invaded by mesodermal tissue, forming the primordium of the palatine tonsils (Fig. 16.10). During the third and fifth months, the tonsil is infiltrated by lymphatic tissue. Part of the pouch remains and is found in the adult as the tonsillar fossa.m

*Third Pharyngeal Pouch *The third and fourth pouches are characterized at their distal extremity by a dorsal and a ventral wing (Fig. 16.10). In the fifth week, epithelium of the *1-dorsal region of the third pouch differentiates into the inferior parathyroid gland, while the *2-ventral region forms the thymus . *Both gland primordia lose their connection with the pharyngeal wall, and the thymus then migrates in a caudal and a medial direction, pulling the inferior parathyroid with it

*Growth and development of the thymus continue until puberty. In the young child, the thymus occupies considerable space in the thorax and lies behind the sternum and anterior to the pericardium and great vessels. In older persons, it is difficult to recognize, since it is atrophied and replaced by fatty tissue. *The parathyroid tissue of the third pouch finally comes to rest on the dorsal surface of the thyroid gland and forms the inferior parathyroid

*Fourth Pharyngeal Pouch *Epithelium of the *dorsal region of the fourth pharyngeal pouch forms the superior parathyroid gland. When the parathyroid gland loses contact with the wall of the pharynx, it attaches itself to the dorsal surface of the caudally migrating thyroid as the superior parathyroid gland (Fig. 16.11). *The ventral region of the fourth pouch gives rise to the ultimobranchial body, which is later incorporated into the thyroid gland. Cells of the ultimobranchial body give rise to the parafollicular, or C, cells of the thyroid gland. These cells secrete calcitonin, a hormone involved in regulation of the calcium level in the blood

*PHARYNGEAL CLEFTS *The 5-week embryo is characterized by the presence of four pharyngeal clefts (Fig. 16.6), of which only one contributes to the definitive structure of the embryo. The dorsal part of the first cleft penetrates the underlying mesenchyme and gives rise to the external auditory meatus (Figs. 16.10 and 16.11). The epithelial lining at the bottom of the meatus participates in formation of the eardrum (see Chapter 18).

*Active proliferation of mesenchymal tissue in the second arch causes it to overlap the third and fourth arches. Finally, it merges with the epicardial ridge in the lower part of the neck (Fig. 16.10), and the second, third, and fourth clefts lose contact with the outside (Fig. 16.10B). The clefts form a cavity lined with ectodermal epithelium, the cervical sinus, but with further development, this sinus disappears.

*TONGUE *The tongue approximately 4 weeks in the form of two lateral lingual swellings and one medial swelling, the tuberculum impar These three swellings originate from the first pharyngeal arch. A second median swelling, the copula, or hypobranchial eminence, mesoderm of the second, third, and ventral part of the fourth arch. Finally, a third median swelling, formed by the posterior part of the fourth arch, marks development of the epiglottis. appears in embryos of is formed by

*As the lateral lingual swellings increase in size, they overgrow the tuberculum impar and merge, forming the anterior two-thirds, or body, of the tongue m. Since the mucosa covering the body of the tongue originates from the first pharyngeal arch, sensory innervation to this area is by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve. The body of the tongue is separated from the posterior third by a V-shaped groove, the terminal sulcus (Fig. 16.17B

*The posterior part, or root, of the tongue originates from the second, third, and part of the fourth pharyngeal arch. The fact that sensory innervation to this part of the tongue is supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve indicates that tissue of the third arch overgrows that of the second. *The epiglottis and the extreme posterior part of the tongue are innervated by the superior laryngeal nerve, reflecting their development from the fourth arch. Some of the tongue muscles probably differentiate in situ, but most are derived from myoblasts originating in occipital somites. Thus, tongue musculature is innervated by the hypoglossal nerve.

*The general sensory innervation of the tongue is easy to understand. The body is supplied by the trigeminal nerve, the nerve of the first arch; that of the root is supplied by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves, the nerves of the third and fourth arches, respectively. Special sensory innervation (taste) to the anterior two thirds of the tongue is provided by the chorda tympani branch of the facial nerve, while the posterior third is supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve

*THYROID GLAND *The thyroid gland appears as an epithelial proliferation in the floor of the pharynx between the tuberculum impar and the copula at a point later indicated by the foramen cecum (Figs. 16.17 Subsequently, the thyroid descends in front of the pharyngeal gut as a bilobed diverticulum (Fig. 16.18). During this migration, the thyroid remains connected to the tongue by a narrow canal, the thyroglossal duct. This duct later disappears and 16.18A).

*With further development, the thyroid gland descends in front of the hyoid bone and the laryngeal cartilages. It reaches its final position in front of the trachea in the seventh week (Fig. 16.18B). By then, it has acquired a small median isthmus and two lateral lobes. The thyroid begins to function at approximately the end of the third month, at which time the first follicles containing colloid become visible. Follicular cells produce the colloid that serves as a source of thyroxine and triiodothyronine. Parafollicular, or C, cells derived from the ultimobranchial body (Fig. 16.10) serve as a source of calcitonin. *P.279 *