Challenges of the Dirigiste Regime in Financial Globalization

The Dirigiste regime faced contradictions in the context of financial globalization, impacting domestic wealth holders and the effectiveness of state interventions. Internal contradictions and the need for state involvement in infrastructure development and economic regulation further complicated the regime's viability. The state struggled to balance investment expenditure for market growth while facilitating capitalist accumulation. The absence of radical land distribution limited market expansion, pointing to the complex challenges encountered by the Dirigiste regime.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

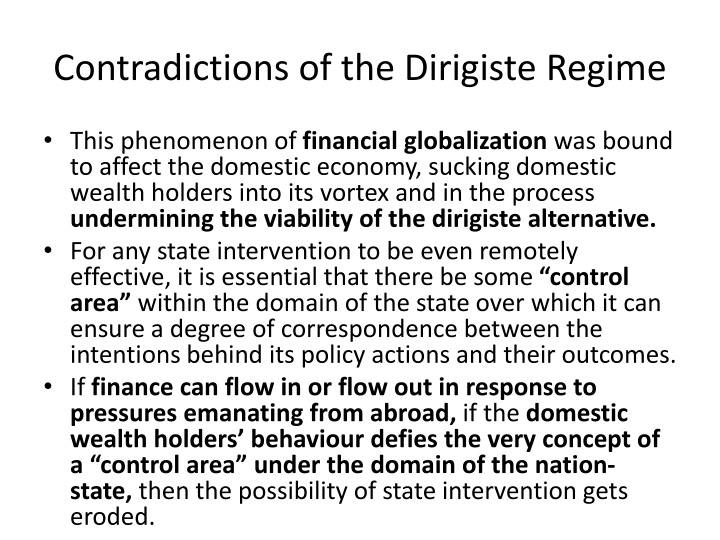

Contradictions of the Dirigiste Regime This phenomenon of financial globalization was bound to affect the domestic economy, sucking domestic wealth holders into its vortex and in the process undermining the viability of the dirigiste alternative. For any state intervention to be even remotely effective, it is essential that there be some control area within the domain of the state over which it can ensure a degree of correspondence between the intentions behind its policy actions and their outcomes. If finance can flow in or flow out in response to pressures emanating from abroad, if the domestic wealth holders behaviour defies the very concept of a control area under the domain of the nation- state, then the possibility of state intervention gets eroded.

Contradictions(contd.) As stated earlier the changed international context was not alone responsible for the eventual transcendence of the dirigiste regime. The regime had serious internal contradictions that contributed to an erosion of its social stability as well as of its economic viability, and propelled it toward a situation where it could not summon the will for any alternative viable responses to the changed context that has already been underscored. The economic policy regime erected in the 1950s had its roots in the freedom struggle itself. The economy had been dominated by metropolitan capital and metropolitan commodities in the pre-independence period.

Contradictions(contd.) Freedom meant freedom from this domination, and this could not be ensured without giving the state in independent India a major role in building up infrastructure, expanding and strengthening the productive base of the economy, setting up new financial institutions, and regulating and coordinating economic activity. This was necessary for building capitalism itself, though Nehru had his ideological conviction and commitment to achieve socialism. Three mutually reinforcing and interrelated contradictions need to be noted. First, the state within the old economic policy regime had to simultaneously fulfill two different roles that were incompatible in the long run. On the one hand it had to maintain growing expenditures, in particular investment expenditure, in order to keep the domestic market expanding. Reasons:

Contradictions(contd.) i. The absence of any radical land distribution had meant that the domestic market, especially for industrial goods, had remained narrowly based socially. It had also meant that the growth of agricultural output, though far greater than in the colonial period, remained well below potential. Under these circumstances, a continuous growth in state spending was essential for the growth of the market. At the same time, however, the state exchequer was the medium through which large- scale transfers were made to the capitalist and proto-capitalist groups. In other words, the state was an instrument for the primary accumulation of capital. ii.

Growth in Governments Revenue Deficit and Fiscal Deficit The contradiction between these two different roles of the state manifested itself (despite increasing resort to indirect taxation and administered price hikes) through a growth in the government s revenue deficit. A result of course was that the fiscal deficit also went up. This, however, reflected not a step-up in public investment but a decline in public savings. The revenue account of the central government-1950-60- was in surplus; in the 1970s-went into a deficit; this deficit climbed steadily from Rs. 20,370 million in 1980-81 to Rs.105,140 million in 1988-89; Rs. 119, 140 million in 1989-90; and Rs. 185, 610 million in 1990-91.

The Implications of this Growing Fiscal Crisis The implications of this growing fiscal crisis were obvious: the government had either to cut back the tempo of its investment or to maintain this tempo through increased recourse to borrowing. If the borrowing is from abroad, then the building up of pressure for a change in the policy regime is obvious. The state would sooner or later have to cut back its expenditure, especially investment expenditure, which would slow down the economy and eventually arouse capitalists demands for an alternative policy regime. In short, the regime gets progressively engulfed in a crisis.

The Second Contradiction It lay in the inability of the state to impose a minimum measure of discipline and respect for law among the capitalists, without which no capitalist system anywhere can be tenable. Disregard for the laws of the land, especially tax laws, was an important component of the primary accumulation of capital. The third contradiction had its roots in the intellectual ambience of an ex-colonial society like India. The market for industrial goods was from its very inception, as we have seen, a narrowly based one socially. Capitalism in its metropolitan centres, however, is characterized by continuous product innovation, the phenomenon of newer and ever newer goods being thrown into the market, resulting in alterations of lifestyles.

The Third Internal Contradiction In an ex-colonial economy like India, the comparatively narrow social segment having additional purchasing power whose growing consumption provides the main source of the growth in demand for industrial consumer goods, is also anxious to emulate the lifestyles prevailing in the metropolitan centre. It is not satisfied with having more and more of the same goods that are domestically produced, nor is it content merely with expending its additional purchasing power upon such new goods as the domestic economy, on its own, is capable of innovating. Its demand is for the new goods that are being produced and consumed in the metropolitan centers and which, given the constraints upon the innovative capacity of the domestic economy, are incapable of being locally produced purely on the basis of indigenous resources and indigenous technology.

The Third Internal(contd.) An imbalance therefore inevitably arises in such economies between what the economy is capable of locally producing purely on its own steam, and what the relatively affluent sections of society who account for much of the growth of potential demand for consumer goods would like to consume. The result is a powerful buildup of pressure among the more affluent groups in society for a dismantling of controls. The slower expansion of public investment also meant a slower growth in the productive potential of the industrial sector on account of the resulting infrastructural constraints.

Bleak Export Prospects of Indian Capital Given the sluggish growth of the home market, breaking into export markets could have provided a new stimulus to industrial expansion and a new basis for capital accumulation in productive channels. But export markets were dominated by metropolitan capital. Thus, the export prospects of Indian capital consequently remained bleak. Support for Fund-Bank-style liberalization was growing not just among a section of capital. A whole new category of an altogether different kind of businessperson was coming up, who was more in the nature of an upstart, international racketeer, fixer, middleman, often of nonresident Indian origin or having nonresident Indian associations, often linked smuggling and the arms trade.

Growing Support for Fund-Bank-style Liberalization The new businesspeople in any case did not have much of a production base, and their parasitic intermediary status as well as the international value of their operations naturally inclined them toward an open economy. And finally, one should not exclude a section of the top bureaucracy itself, which had close links with the Fund and Bank, either as ex-employees who might return any time to Washington D.C., or as someone engaged in dollar projects of various kinds, or as someone having some other aspirations. The weight of this section in the top bureaucracy had been growing rapidly, and its inclination naturally was in the direction of the Fund-Bank policy regime.

Concluding Observations Thus, quite apart from the growing leverage exercised by the international agencies in their capacity as donors, the internal contradictions of the Nehruvian dirigiste policy regime generated increasing support within the powerful and affluent sections of society for changing the regime in the manner desired by these agencies.