Challenges and Approaches in Feminist Critique of Globalization

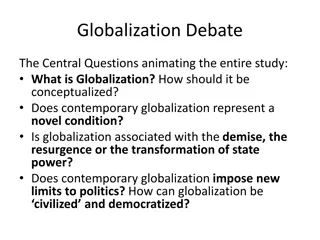

The feminist perspective on globalization highlights the need for a counter-hegemonic global regime that prioritizes democratic political control and equitable development. Different feminist approaches address gender injustices, with an emphasis on specific, concrete issues. Early feminist analyses were criticized for overlooking systematic gendered injustices associated with neoliberalism. Feminist values of opposing women's subordination and using human rights language are essential features of feminist critiques of globalization.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

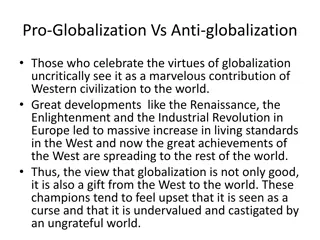

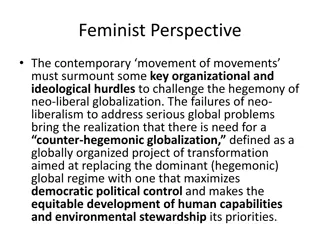

Feminist Perspective The contemporary movement of movements must surmount some key organizational and ideological hurdles to challenge the hegemony of neo-liberal globalization. The failures of neo- liberalism to address serious global problems bring the realization that there is need for a counter-hegemonic globalization, defined as a globally organized project of transformation aimed at replacing the dominant (hegemonic) global regime with one that maximizes democratic political control and makes the equitable development of human capabilities and environmental stewardship its priorities.

Different Feminist Approaches Feminist theoretical approaches to globalization is an umbrella term that refers to a number of specific theoretical approaches that feminists have used to articulate the challenges that globalization poses for women, people of color, and the global poor. These various approaches include those developed by postcolonial feminists, transnational feminists, and feminists who endorse an ethics of care.

Key Features Feminist approaches to globalization seek to provide frameworks for understanding the gender injustices associated with globalization. Rather than developing all-encompassing ideal theories of global justice feminist philosophers tend to adopt the non-ideal theoretical perspectives, which focus on specific, concrete issues. Early feminist analyses focused on issues that were widely believed to be of particular importance to women around the world, such as domestic violence, workplace discrimination, and human rights violations against women. Many feminist philosophers view this approach as too narrow, both in terms of the specific issues it addresses and its methodological approach to these issues.

Limitations of Early Feminists Moreover, by addressing specific global women s issues as independent phenomena, early feminist analyses failed to take into account the systematic and structural gendered injustices associated with neoliberalism. Although gender oppression takes different forms in different social, cultural, and geographical locations, women in every society face systematic disadvantages, such as those resulting from their socially assigned responsibility for domestic work. Because of these structural injustices, women of all nationalities tend to suffer more from the poverty, overwork, deprivation, and political marginalization associated with neoliberal policies. Thus, more recent feminist analyses of globalization tend to understand the outcomes of globalization not as disparate or contingent phenomena, but rather as a result of systematic, structural injustices on a global scale.

Key Features (Contd.) Another key feature of feminist approaches to globalization is a shared commitment to core feminist values, including an opposition to the subordination of women. Many feminists also use the language of human rights to address the challenges of globalization. While they acknowledge that traditional understandings of human rights are implicitly male-biased, they contend that feminist rearticulations of these norms can help to identify the gendered harms involved in sexual slavery, forced domestic labor, and the systematic withholding of education, food, and healthcare from women and girls that follow from severe economic deprivation.

Relational Model However, not all feminist political philosophers agree with this approach. Some believe that new feminist ideals, such as relational understandings of power, collective responsibility, and mutual dependence, are needed to diagnose the gender injustices associated with globalization. For example, Iris Marion Young argues that the traditional ideal theories of justice are unable to account for the unjust background conditions that contribute to the development of sweatshops in the global South. She argues that a new relational model of responsibility, which she calls the social connection model, is needed to articulate the obligations that people in affluent northern countries have to workers in the global South.

Social Connection Model of Iris Marion Young The social connection model holds that individuals bear responsibility for structural injustices, such as those suffered by workers on the global assembly line, because our actions contribute to the institutional processes that produce such injustices. In particular, northern consumers have a responsibility to organize collectively to reform the injustices associated with sweatshop labor.

Feminist Methodologies The third key feature of feminist approaches to globalization is an emphasis on feminist methodologies. In particular, these approaches tend to embody three key methodological commitments. The first is intersectionality, which maintains that systems of oppression interact to produce injustices, and thus, that gender injustices cannot be understood solely in terms of sex or gender. Feminists who theorize about justice on the domestic level argue that women s experiences of gender oppression are shaped by other forms of oppression, such as those based on race, class, disability, and sexual orientation. Feminist theorists of globalization contend that gender oppression interacts with these systems of oppression, along with other forms of systematic disadvantage that arise within the global context.

Methodological Commitments (contd.) Given this broad conception of intersectionality, feminist theorists of globalization insist that gender injustices arise within specific transnational contexts, such as historical relationships among nations and current global economic policies. The second methodological commitment shared by feminist approaches to globalization is a sensitivity to context and concrete specificity. Feminist philosophers strive to accurately reflect the diverse interests, experience, and concerns of women throughout the world, and to take seriously differences in culture, history, and socio-economic and political circumstances.

A View Different from that of the International Feminists This has led some feminist theorists of globalization to distinguish their views from well-known feminists, such as Martha Nussbaum and Susan Okin, whom Ackerly and Attanasi refer to as international feminists by virtue of their methodological commitments. In their view, Nussbaum and Okin do not pay sufficient attention to the ways that justice and injustice are mediated by local conditions in their attempts to identify universal moral ideals. As a result, their theories tend to privilege Western perspectives and undermine their own commitment to reflecting women s lived experience (Ackerly and Attanasi 2009).

Self-reflexive Critiques Finally, feminist theorists of globalization are committed to developing self-reflexive critiques. At the heart of this methodology is a willingness to critically examine feminist claims, with particular attention to the ways in which feminist discourses privilege certain points of view. For instance, Schutte insists that ostensibly universal feminist values and ideas are likely to embody the values of dominant cultures. This helps to explain why the voices of women from developing countries are often taken seriously only if they reflect the norms and values of the West and conform to Western expectations. Thus, Schutte insists that feminists must engage in methodological practices that de-center their habitual standpoints and foreground perspectives that challenge accepted ways of thinking (Schutte 2002).

Rejection of Enlightenment Liberal Values Transnational feminists are urged to reject the problematic variants of Enlightenment liberal values taken to be central to Western feminism, including individualism, autonomy, and gender-role eliminativism (Khader 2019, 3). Such values not only constitute cultural imperialism when imposed on cultural others, as Schutte argues, but also can serve to justify militarism, political domination, economic exploitation, and white supremacy in the name of advancing gender interests (Khader 2019). Ackerly argues that feminist theory can be used not only to critique feminist ideals and values, but also to develop richer ways to evaluate the work done by women s human rights organizations. Feminist theory is able to engage with, shape and be shaped by the work being done on the ground by NGOs and other groups (Ackerly 2009).

Feminist Theories in the 1980s The struggle to develop feminist theories that embody these methodological commitments has been ongoing for feminists. In the 1980s, Chandra Talpade Mohanty observed that Western feminist scholarship tends to adopt an ethnocentric perspective, depicting so-called Third-World women as one-dimensional, non-agentic, and homogenous. Such scholarship tends to suggest that the average Third World woman leads an essentially truncated life based on her feminine gender (read: sexually constrained) and her being Third World (read: ignorant, poor, uneducated, tradition-bound, domestic, family-oriented, victimized, etc.). This, she suggests, is in contrast to the (implicit) self- representation of Western women as educated, as modern, as having control over their own bodies and sexualities and the freedom to make their own decisions (Mohanty 2003, 22).

Feminist Theories in the 1980s (Contd.) Mohanty claims that this perspective leads to a simplistic understanding of what feminists in Western countries can do to help women in developing nations. Many of the recent developments in the feminist literature on globalization can be understood as a response to this theoretical failure. In addition to recognizing the ways in which power influences the production of feminist theories, feminist critics of globalization strive to understand the ways in which Western women share responsibility for gender injustices in developing countries and at home, and to articulate their obligations to eliminate these injustices.

Distinctive Feminist Approaches Despite these common aims and methodological commitments, feminists have analyzed globalization from a number of different theoretical perspectives. It is in the fitness of things to examine here three prominent approaches to globalization, developed by postcolonial and decolonial, transnational, and ethics of care feminists. Although it is not possible to draw sharp boundaries around these theoretical perspectives, some distinctive features of each may be identified for the present analysis.

Postcolonial and Decolonial Feminisms Postcolonial and decolonial feminisms offer primarily critical theoretical frameworks, which analyze globalization within the context of the history of Western colonialism and imperialism. They begin with the claim that Western colonialism and imperialism have played important roles in shaping the contemporary world, and highlight their enduring effects on global relations and local cultural practices. Although postcolonial and decolonial feminists write from all over the world, they foreground non- Eurocentric epistemic standpoints and criticize North- South power asymmetries from the diverse perspectives of members of Indigenous communities and people in the global South (Herr 2013, Khader 2019, McLaren 2017, Schutte 2002, 2005).

Postcolonial and Decolonial---(Contd.) First, they insist that it is impossible to understand local practices in developing countries without acknowledging the ways in which these practices have been shaped by their economic and historical contexts, particularly their connection to Western colonialism and imperialism. Thus, postcolonial and decolonial feminists insist that any feminist analysis of the harms of globalization must take seriously the history and ongoing cultural, economic, and political effects of colonialism and imperialism and analysis of suffering of women in developing countries in simplistic terms often tends to reproduce a colonial stance toward the global South. For example, as explained earlier, Chandra Mohanty sees elements of imperialism in Western feminist scholarship on women in the global South. Similarly, Uma Narayan criticizes feminists for unwittingly adopting a Eurocentric perspective. Highlighting the role that colonialism has played in shaping local practices enables feminists to avoid adopting a Eurocentric perspective.

Postcolonial and Decolonial Feminists Attack on Neo-colonialism Postcolonial and decolonial feminists further argue that although traditional forms of colonialism have formally ended, many aspects of globalization are best understood as neo-colonial practices. Multinational corporations and global businesses, largely centered in Western nations, bring their own colonizing influence through business models, hegemonic culture, exploitation of workers, and displacement of traditional trades. Old style colonialism often killed or displaced indigenous peoples; the new style of colonialism impoverishes a culture by swamping society with Western values, products or ideals (Sally Scholz, 2010:139).

Attack on Neoliberalism More broadly, postcolonial and decolonial feminists observe that many of the conditions created by colonialism economic inequality and exploitation, racism, cultural marginalization, and the domination of the global South by the global North have been sustained and intensified by neoliberalism. Moreover, they argue, neoliberal policies and institutions systematically favor countries in the global North to the detriment of southern nations. International trade policies serve Western interests even while claiming to be politically neutral and fair. Global economic institutions also privilege Western culture and political norms, presenting them as models for the rest of the world, while ignoring and marginalizing the claims of women s and indigenous movements in the global South as well as settler nations (Weendon 2002).

Attack on Neoliberalism (Contd.) Since appeals to so-called universal concepts, epistemologies, and values, such as freedom, rights, and autonomy, can be used to further imperialist projects, postcolonial and decolonial feminists seek to develop normative positions that criticize neoliberal and neocolonial practices while rejecting problematic ethnocentric ideals that often masquerade as universal (Alcoff 2017, Khader, 2019, McLaren 2017, Pohlhaus Jr. 2017, Weir 2017).

Ethic of Care Feminists This school of feminist theoretical responses to globalization puts care, both caring labor the work of caring for the young, old, sick, and disabled, and the everyday maintenance of households and the moral ideal of care, at the center of its analyses. Proponents of this approach begin by observing that most mainstream analyses of globalization either ignore or devalue care which is problematic for at least three reasons:

Ignoring or Devaluing Care Problematic for Three Reasons i. Care work, which is done almost exclusively by women, has been profoundly influenced by globalization; The values and work associated with care are both undervalued and insufficiently supported, and this contributes to gender, racial, and economic inequality, both within countries and between the global North and the global South; and iii. Any viable alternative to neoliberal globalization must prioritize the moral ideal of care. Thus, ethics of care approaches to globalization have both theoretical and practical dimensions. ii.

Assumptions of Neoliberalism Chellenged In their view, neoliberalism presupposes a problematic notion of the self, which posits individuals as atomistic, independent, and self- interested, and an inaccurate social ontology, which suggests that human relationships are formed by choice rather than necessity or dependency. These assumptions lead neoliberalism to prioritize economic growth, efficiency, and profit making over other values, such as equality, human rights, and care. Ethics of care feminists reject these assumptions. In their view, human beings are fundamentally relational and interdependent; individuals are defined, indeed constituted, by their caring relationships.

Relational Values: The Basis of Just Forms of Globalization All persons experience long periods during which their lives literally depend on the care of others, and everyone needs some degree of care in order flourish. Thus, vulnerability, dependency, and need should be understood not as deficits or limitations, but rather as essential human qualities requiring an adequate political response. Ethics of care feminists contend that relational values, including care, should form the basis of more just forms of globalization. Because a global care ethics begins with a relational ontology, it requires global political leaders to develop social and economic policies that aim to meet human needs and reduce suffering rather than to expand markets and increase economic competition (Hankivsky 2006).

Global Duty to Care Held endorses a similar view. According to her, an ethic of care requires leaders to foster a global economy that is capable of meeting universal human needs (Held 2004, 2007). Similarly, Miller advocates a global duty to care, which requires individuals to take responsibility for their role in contributing to global oppression, and obligates leaders to advocate for institutions that embody the moral value of care (Miller 2006). Concretely, feminist theorists who favor an ethics of care approach highlight the role of care work in the global economy and put forth recommendations for reevaluating it.

The Global Distribution of Care Work Robinson develops a relational moral ontology that sheds lights on the features of globalization that are usually invisible: the global distribution of care work and the corresponding patterns of gender and racial inequality. He highlights on the under-provision of public resources for care work in both developed and developing countries; and the ways in which unpaid or low-paid care work sustains cycles of exploitation and inequality on a global scale (Robinson 2006a, 2006b). Similarly, Held advocates for increased state support of various forms of care work and for policies designed to meet people s needs in caring ways (Held 2004, 2007).

Transnational Feminism In its broadest sense, transnational feminism maintains that globalization has created the conditions for feminist solidarity across national borders. On the one hand, globalization has enabled transnational processes that generate injustices for women in multiple geographical locations, such as the global assembly line. Yet on the other, the technologies associated with globalization have created new political spaces that enable feminist political resistance. Thus, transnational feminists incorporate the critical insights of postcolonial, Third World and ethics of care feminists into a positive vision of transnational feminist solidarity.

Transnational Feminism Vs Global Feminism However, transnational feminism differs from global feminism in at least three significant respects: First, transnational feminism is sensitive to differences among women. Global feminists argue that patriarchy is universal; women across the globe have a common experience of gender oppression. They promote the recognition of a global sisterhood based on these shared experiences, which transcends differences in race, class, sexuality, and national boundaries. This solidarity is thought to provide a unified front against global patriarchy.

Transnational Feminism Vs Global Feminism (Contd.) Transnational feminists also advocate for solidarity across national boundaries. However, their approach emphasizes the methodological commitments discussed above, specifically intersectionality, sensitivity to concrete specificity, and self- reflexivity. Transnational feminists are careful to point out that although globalizing processes affect everyone, they affect different women very differently, based on their geographical and social locations. They are also quick to acknowledge that many aspects of globalization may benefit some women while unduly burdening many others. Second, transnational feminist solidarity is political in nature. Whereas global feminists advocate a form of social solidarity defined on the basis of characteristics shared by all women, such as a common gender identity or experience of patriarchal oppression, transnational feminist solidarity is grounded in the political commitments of individuals, such as the commitment to challenge injustice or oppression.

Transnational Feminist Solidarity Based on Shared Political Commitments Because transnational feminist solidarity is based on shared political commitments rather than a common identity or uniform set of experiences, advantaged individuals, including those who have benefited from injustice, can join in solidarity with those who have experienced injustice or oppression directly (Ferguson 2009, Scholz 2008). The emphasis on shared political commitments also enables feminists to resist oppressive conditions that manifest differently in different geographical locations but are nonetheless prevalent in many countries, such as racialized violence against women (Khader 2019, 44 48). Third, transnational feminists focus on specific globalizing processes, such as the growth of offshore manufacturing, rather than a theorized global patriarchy, and often take existing transnational feminist collectives as a model for their theoretical accounts of solidarity.

Concluding Observations On the whole, globalization presents a number of challenges to feminist political philosophers who seek to develop conceptions of justice and responsibility capable of responding to the lived realities of both men and women. As globalization will most certainly continue, these challenges are likely to increase in the coming decades. As outlined above, feminist political philosophers have already made great strides towards understanding this complex phenomenon. Yet the challenge of how to make globalization fairer remains for feminist philosophers, as well as all others who strive for equality and justice.