Aristotle's Virtue Ethics: The Nature and Kinds of Virtues

Aristotle's virtue ethics discusses the nature of virtues as a disposition unique to humans that enables them to function well according to reason. Virtue involves finding the mean between excess and deficiency, not endorsing mediocrity. It emphasizes that virtues are acquired through habitual practice and guided by reason, not innate qualities. Choosing the mean is essential, except for actions that are inherently evil. A virtuous person serves as a role model for moral decision-making.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

Programme: BA Philosophy Course: Ethics TDC 2ndSemester 2019 Unit-II Virtue Ethics Aristotle: Nature and Kinds of Virtues -presentation by Paran Borthakur Associate Professor of Philosophy, Haflong Government College

Aristotle: The Nature and Kinds of Virtue From Aristotle s(384-322 BC) viewpoint virtue is a disposition peculiar to human beings which makes them perform their specific function well. The specific function of man is reason. Thus, virtue consists in appropriate functioning of reason. It constitutes good the ultimate moral ideal. A good life is a life of virtuous activities. Eudaemonia (happiness, wellbeing or flourishing) consists only on that.

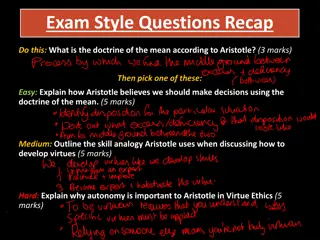

As Aristotle defines Virtue is purposive disposition, lying in a mean that is relative to us and determined by a rational principle, and by that which a prudent man would use to determine it (Nicomechean Ethics). In the spheres of feelings and actions, both the deficiency and excess are vices but the mean is the right course and it is the excellence. The doctrine of mean is a guiding rule which suggests the right course of action but it is not a defining characteristic of virtue because some of the feelings or actions are essentially evil irrespective of their being excess, deficiency or mean.

Doctrine of mean is also not endorsing mediocrity because virtue is excellence in the sphere of activities. Virtues are not innate but acquired by habits. The tendencies for evil course of action should be made weak by resisting them and suppressing the corresponding evil feelings which are either in excess or deficient in any sphere of human activity or feelings. The right course of action has to be strengthened by repeated performance. There may be innate or natural good qualities a person may be endowed with but these are not considered to be virtues since these are not developed through rational faculties such as theoretical and practical wisdom. Without the guidance of reason or intellect, good innate dispositions are blind and cannot qualify for moral virtues.

Virtue consists in choosing the mean. However, this rule is not applicable to all cases because some of actions are essentially evil. For example, such feelings such as malice, shamelessness, envy etc.; and actions such as theft, adultery, murder etc. are evils in themselves and having and doing them in moderation will make no difference to these. A prudent or virtuous man is the exemplar who sets example for the moral agents in choosing or deciding the right course of activity in the right way.

Kinds of Virtues Aristotle classified virtues into two class: 1) Moral Virtues & 2) Intellectual Virtues. He makes a detailed discussion about both of these classes of virtues in Nicomachean Ethics: Intellectual virtue owes both its inception and its growth chiefly to instruction, and for this very reason need time and experience. Moral goodness, on the other hand, is the result of habit. By repeated performance of virtuous actions the moral agent acquire the moral virtues. For example, courage is a virtue which is acquired by perpetual performance of courageous acts. And virtues are exercised in same kind of activities from which they are generated.

The rule of choosing the mean between the two extremes make the account of the virtues more distinct if we apply it to the different feelings and actions. In the domain of Fear and Confidence the mean is Courage while extreme of fearlessness has no name but excess of confidence is Rashness and excessive fear and lack of confidence is called Cowardice. Courage is the mean and is a virtue while Rashness & Cowardice are two vices remaining in the extremes.

In matters of pleasure and pain the mean is Temperance while over indulgence is Licentiousness. Deficiency in seeking pleasure is rare and has no name but can be called Insensibility. In case of giving and taking of money moderation is the virtue called Liberality. Excess is called Prodigality and deficiency is Illiberality. This is about transaction of small amount.

In matters of making larger amount of getting and spending the virtue is Magnificence while excess is Tastelessness and Vulgarity. Deficiency is Pettiness. The following is a table showing the excess, deficiency and the mean in different feelings and action as given by J A K Thomson.

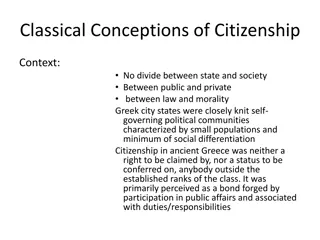

Moral Virtues* Excess Sphere of action & Feeling Mean Deficiency Fear and Confidence Rashness Courage Cowardice Pleasure and Pain Licentiousness Temperance Insensibility Getting and Spending (Minor) Prodigality Liberality Illiberality Getting and Spending (Major) Vulgarity Magnificence Pettiness Honour and Dishonour (Major) Vanity Magnanimity Pusillanimity Honour and Dishonour (Minor) Ambition Proper Ambition Unambitiousness Anger Irascibility Patience Lack of Spirit

Sphere of action & Feeling Excess Mean Deficiency Self-expression Boastfulness Truthfulness Understatement Conversation Buffoonery Wittiness Boorishness Social Conduct Obsequiousness/ Flattery Friendliness Cantankerousness Shame Shyness Modesty Shamelessness Indignation Envy Righteous Indignation Malicious enjoyment

Intellectual Virtues* According to Aristotle, the intellectual virtues are related to the faculties of the soul. The soul has two faculties (1) the scientific faculty (to epistemonokon) by which we contemplate objects that are necessary and admit of no contingency, and (2) the calculative faculty (to logistikon) or the faculty of opinion, which is concerned with objects that are contingent

. The intellectual virtues of the scientific faculty are: (a)Episteme, the disposition by virtue of which we demonstrate and make proofs, (b) Nous or Intuitive Reason, whereby we grasp a universal truth after experience of a certain number of particular instances and then see this truth or principle to be self-evident;

(c) Sophia is Theoretical Wisdom. This is the union of nous and episteme. It is directed to the highest objects probably including not only the objects of metaphysics but also those of Mathematics and Natural Science. Contemplation of these objects belongs to the ideal life for man.

The virtues of the other faculty or part of the soul called logistikon are: (i) Techne or Art which is the disposition by which we produce things with the help of rules that guide how to do things. (ii) Phronesis or Practical Wisdom is a true disposition towards action, by aid of rule, with regard to things good or bad for men. This is crucially related to moral virtues.

Phronesis is subdivided according to the objects it is concerned with: 1. Phronesis in the narrow sense: it is concerned with the individual s good. 2. Economics: phronesis concerned with family and household management. 3. Political Science: Phronesis concerned with the state. This further subdivides into Legislative and Administrative faculties. Administrative faculty again subdivides into Deliberative and Judicial.

According to Aristotle virtue is not only the right or reasonable attitude, but the attitude which leads to right and reasonable choice which is prudence. Prudence, therefore, is necessary for the truly virtuous man since it is the excellence of an essential part of our nature. Theoretical wisdom chooses the right end while practical wisdom makes the right choice regarding the mean.

Aristotle also mentions some more intellectual qualities in Nicomechean Ethics. These are: 1. Cleverness (Deinotes) is another disposition by which a man is enabled to find right means to any particular end. Cleverness sometimes may not be guided by vision of the right end and right choice of the mean. 2. Understanding (Sunesis) which is ability to deliberate on the perplexing things. It makes judgments but unlike prudence its judgments are not imperatives. 3. Judgment (Gnome) by which people make considerate judgment which are equitable.