Argument from Causation in Existence of God

This argument discusses the existence of God based on the causation of sense ideas being attributed to a higher mind. It delves into the distinction between vivid sensory ideas and faint imaginative thoughts, concluding that God is the source behind sensory perceptions.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

You are allowed to download the files provided on this website for personal or commercial use, subject to the condition that they are used lawfully. All files are the property of their respective owners.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

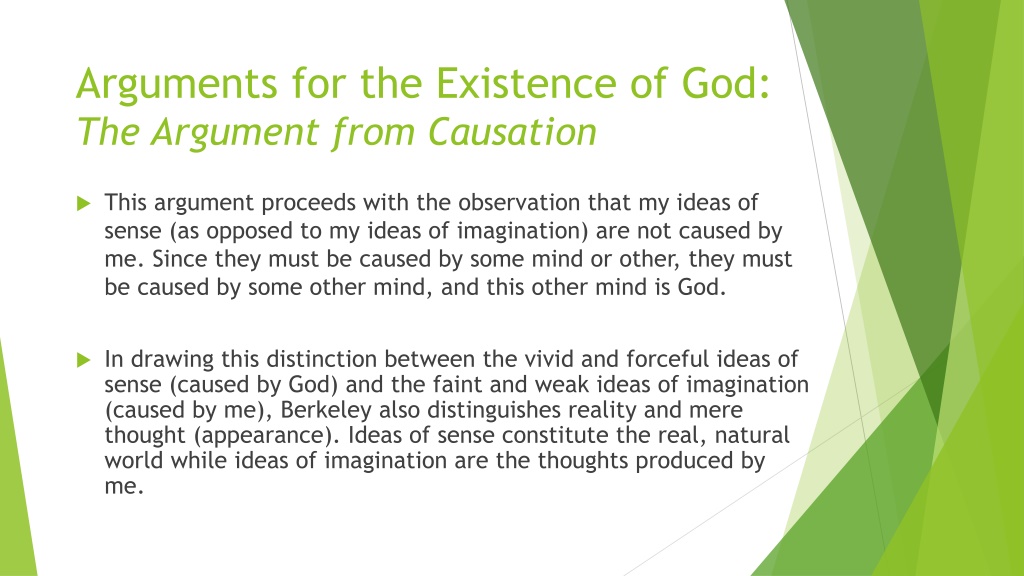

Arguments for the Existence of God: The Argument from Causation This argument proceeds with the observation that my ideas of sense (as opposed to my ideas of imagination) are not caused by me. Since they must be caused by some mind or other, they must be caused by some other mind, and this other mind is God. In drawing this distinction between the vivid and forceful ideas of sense (caused by God) and the faint and weak ideas of imagination (caused by me), Berkeley also distinguishes reality and mere thought (appearance). Ideas of sense constitute the real, natural world while ideas of imagination are the thoughts produced by me.

(1) (2) (3) Sensible ideas must be caused by some spirit I am not the cause of my sensible ideas So: There must be some other spirit which causes my sensible ideas (4) This spirit is God.

The Argument from Perception (1) (2) (3) Sensible things cannot exist unperceived Sensible things exist independently of my perception So: There must be some other spirit which perceives my sensible ideas (4) This spirit is God.

This argument proceeds with the Berkeleyan claim that sensible things cannot ever exist unperceived (i.e. his basic idealism). The second claim is that sensible things exist independently of my own mind (i.e. exist independently of being perceived by me). From this it follows that there is another mind which perceives sensible things (e.g. when I don t perceive them) keeping them in existence. This other mind is God. The first claim in this argument depends upon Philonous arguments in the First Dialogue that sensible things are mind- dependent. Recall that this forced Hylas to become a skeptic (i.e. to deny that reality of sensible things). By contrast, Philonous uses this claim of mind-dependence to help advance this original proof of God s existence. Notice that he spends considerable time saying how beautiful everything is and that men who deny the existence of such sensible things deserved to be laughed at.

It is an interesting question how Berkeley thinks he can defend the second claim (i.e. sensible things exist independently of my own mind). One natural thought is that this is simply an appeal to common sense ( Well of course that tree exists even when I don t perceive it!!!! That s only common sense!!! ). One concern with this is that Berkeley s very own position appears to undermine this common sense view of the world. His subsequent appeal to it would consequently appear ad hoc. That said, more can be said in defense of this move.

If Berkeley is right that sensible things are mind-dependent, then we can agree that one of two things occurs when we leave a room. (1) Everything in the room ceases to exist; or (2) Some mind (God) exists and perceives those objects. So which position is closer to common sense? Surely the last position is more common-sensical (especially if we recognize how many human beings actually do believe in God already). Since the whole game between Hylas and Philonous involves staying closer to common-sense, this commitment can further motivate option (2).

However, there is a deeper reason in favor of the view that the sensible things I perceive are independent of me is that, since they are caused by another mind, then they must exist in that other mind, and can consequently exist in that other mind, independently of me. This suggestion would help connect The Causation Argument and The Perception Argument together.

Berkeley on Abstraction The philosophical problem of abstraction concerns whether or not abstractions are real and what their ontology may be. Berkeley himself outlines abstraction in his Principles of Human Knowledge, which I quote below:

It is agreed on all hands, that the qualities or modes of things do never really exist each of them apart by itself, and separated from all others, but are mixed, as it were, and blended together, several in the same object. But we are told, the mind being able to consider each quality singly, or abstracted from those other qualities with which it is united, does by that means frame to itself abstract ideas. Not that it is possible for colour or motion to exist without extension: but only that the mind can frame to itself by abstraction the idea of colour exclusive of extension, and of motion exclusive of both colour and extension.

Berkeleys critique is three-fold: 1) Berkeley s initial argument is that it is impossible to abstract ideas according to Locke s account. For example, Lockean colours are secondary qualities that exist only in the mind and have no extension. Berkeley contends that Locke s theory would require his intellect to abstract an idea of color that is not determinate. Berkeley skeptically claims that he cannot produce such an idea.

2) Due to the titanic influence of William of Ockham on modern philosophy, one of the hallmarks of any modern discourse is an insistence on parsimony. Berkeley argues that Locke s theory of abstraction is unnecessarily complicated and adds little explanatory value in comparison to his preferred theory of subjective idealism.

3) Berkeleys final and most convincing criticism of Locke is that his theory leads to a contradiction. Berkeley uses the example of a Lockean abstract idea of a triangle. Berkeley argues that this idea must be neither oblique nor rectangle, neither equilateral, equicrural, nor scalenon, but all and none of these at once .

Consequences if Berkeley is right: Independently-existing real properties of perceptible objects are impossible. This means the complex ideas of objects depend on regularities in the relations between the elements of diverse perceptions of perceived objects, not on the instantiation of independently-existing distinguishable properties in real objects.