The American Revolution: From Conflict to Independence

The American Revolution, spanning from 1775 to 1783, was ignited by events in Boston and escalated with key battles like Lexington and Concord. General Thomas Gage's actions led to the mobilization of rebel forces, culminating in the Battle of Bunker Hill. This period saw the rise of local militias and the struggle for independence against British rule.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

United States History I Module 5: The American Revolution (1775 1783)

Module Learning Outcomes Compare American civilizations before European contact and the events and motivations for European exploration to the Americas 5.1: Analyze the events that set the stage for the American Revolution and describe its beginnings 5.2: Describe the British and American strategies and the key battles during the war 5.3: Describe the resolution and aftermath of the American Revolutionary War 5.4: Sift, question, and interpret complex material: Use the SIFT Method to evaluate sources

Learning Outcomes: The Revolution Begins 5.1: Analyze the events that set the stage for the American Revolution and describe its beginnings 5.1.1 Describe the beginnings of the American Revolution 5.1.2 Analyze the motives of those who argued for and against independence 5.1.3 Explain the activities of the Second Continental Congress leading to the Declaration of Independence

Introduction to The Revolution Begins What you ll learn to do: describe the beginning of the American Revolution

Fighting Begins In an effort to restore law and order in Boston, the British dispatched General Thomas Gage to the New England seaport. He arrived in Boston in May 1774 as the new royal governor of the Province of Massachusetts, accompanied by several regiments of British troops. Both the British and the rebels in New England began to prepare for conflict by turning their attention to supplies of weapons and gunpowder. General Gage stationed 3,500 troops in Boston, and from there he ordered periodic raids on towns where guns and gunpowder were stockpiled, hoping to impose law and order by seizing them. Gage s actions led to the formation of local rebel militias that were able to mobilize in a minute s time. These minutemen, many of whom were veterans of the French and Indian War, played an important role in the war for independence.

Fighting Begins After the battles of Lexington and Concord, New England fully mobilized for war. Thousands of militias from towns throughout New England marched to Boston, and soon the city was besieged by a sea of rebel forces. In June, 1775, General Gage resolved to take Breed s Hill and Bunker Hill, the high ground across the Charles River from Boston, a strategic site that gave the rebel militias an advantage since they could train their cannons on the British. In the Battle of Bunker Hill, on June 17, the British launched three assaults on the hills, gaining control only after the rebels ran out of ammunition. British losses were very high over two hundred were killed and eight hundred wounded and, despite his victory, General Gage was unable to break the colonial forces siege of the city. In August, King George III declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion.

Fighting Begins While Patriots in Massachusetts engaged the British army, the Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia voted to form a Continental Army, naming Virginia delegate George Washington commander in chief on June 15, 1775. The newly-named General Washington used the Fort Ticonderoga cannons to force the evacuation of the British from Boston. On March 17, 1776, the British evacuated their troops to Halifax, Nova Scotia by sea, ending the nearly year-long siege.

Common Sense and the Declaration of Independence Following the events at Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress convened in May 1775 in Philadelphia, and the Congress struggled to organize a response. The Continental Congress struck a compromise, agreeing to adopt the Massachusetts militia and form a Continental Army, naming Virginia delegate George Washington commander in chief. In the opening months of 1776, independence, for the first time, became part of the popular debate. Thomas Paine s Common Sense argued for independence by denouncing monarchy and challenging the logic behind the British Empire.

Common Sense and the Declaration of Independence On May 10, 1776, nearly two months before the issuance of the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress voted on a resolution calling on all colonies that had not already established revolutionary governments to do so and to wrest control from royal officials. The Congress also recommended that the colonies should begin preparing new written constitutions. In many ways, this was the Congress s first declaration of independence. Neither the grievances nor the rhetoric of the preambleof the Declaration of Independence were new. Instead, they were the culmination of both a decade of popular resistance to imperial reform and decades more of long- term developments that saw both sides develop incompatible understandings of the British Empire and the colonies place within it. The Congress approved the document on July 4, 1776.

Practice Question 1 Why did many colonists come to support independence? A. Many colonists believed they were in an intolerable position in the British empire and independence was the only solution. B. Thomas Paines Common Sense argued for an American monarchy and independence from the British monarchy. C. Dunmore s Proclamation declared that slavery would be abolished if American independence were achieved.

Learning Outcomes: The War for Independence 5.2: Describe the British and American strategies and the key battles during the war 5.2.1 Explain the British and American strategies of 1776 through 1778 5.2.2 Identify the key battles of the early years of the Revolution 5.2.3 Analyze the relative military strengths and weaknesses of England and the colonies during the war 5.2.4 Outline the British southern strategy and its results 5.2.5 Describe key American victories and the end of the war

Introduction to The War for Independence What you ll learn to do: describe the British and American strategies and the key battles during the war

The Early Years of the Revolution After evacuating Boston in March 1776, British forces sailed to Nova Scotia to regroup. General William Howe, commander in chief of the British forces in America, amassed thirty-two thousand troops on Staten Island in June and July 1776. His brother, Admiral Richard Howe, controlled New York Harbor. On September 16, 1776, George Washington s forces held up against the British at the Battle of Harlem Heights. This important American military achievement occurred as most of Washington s forces retreated to New Jersey. A few weeks later, on October 28, General Howe s forces defeated Washington s at the Battle of White Plains and New York City fell to the British. For the next seven years, the British made the city the headquarters for their military efforts to defeat the rebellion, which included raids on surrounding areas.

The Early Years of the Revolution When the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in May 1775, members approved the creation of a professional Continental Army with Washington as commander in chief. Although sixteen thousand volunteers enlisted, it took several years for the Continental Army to become a truly professional force. in late 1776 and early 1777, Washington broke with conventional eighteenth-century military tactics that called for fighting in the summer months only. Intent on raising revolutionary morale after the British captured New York City, he launched surprise strikes against British forces in their winter quarters.

The Early Years of the Revolution During the winter of 1777 1778, the British occupied the city of Philadelphia, and Washington s army camped at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Washington s winter at Valley Forge was a low point for the American forces. A lack of supplies weakened the men, and disease took a heavy toll. Amid the cold, hunger, and sickness, soldiers deserted in droves. Assistance came to Washington and his soldiers in February 1778 in the form of the Prussian soldier Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben. Baron von Steuben was an experienced military man, and he implemented a thorough training course for Washington s ragtag troops. By drilling a small corps of soldiers and then having them train others, he finally transformed the Continental Army into a force capable of standing up to the professional British and Hessian soldiers.

The Early Years of the Revolution The British plan to isolate New England ended in disaster. The American victory at the Battle of Saratoga was the major turning point in the war. A Treaty of Amity and Commerce was signed on February 6, 1778 between France and the new nation. The treaty effectively turned a colonial rebellion into a global war as fighting between the British and French soon broke out in Europe and India. The war quickly became more difficult for the British, who had to fight the rebels in North America as well as the French in the Caribbean. Following France s lead, Spain joined the war against Great Britain in 1779, though it did not recognize American independence until 1783. The Dutch Republic also began to support the American revolutionaries and signed a treaty of commerce with the United States in 1782.

War in the South By 1778, the war had turned into a stalemate. Although some in Britain, including Prime Minister Lord North, wanted peace, King George III demanded that the colonies be brought to obedience. To break the deadlock, the British revised their strategy and turned their attention to the southern colonies, where they could expect more support from Loyalists. The southern colonies soon became the center of the fighting. The southern strategy brought the British success at first, but thanks to the leadership of George Washington and General Nathanael Greene and the crucial assistance of French forces, the Continental Army defeated the British at Yorktown, effectively ending further large-scale operations during the war.

War in the South When the fighting began in 1775, the notion that the militias of the 13 colonies could defeat the British seemed unimaginable. The British population outnumbered the colonists substantially (7.5 million to 2.5 million). The British had the world s finest army and navy, and maintaining their empire meant their military was experienced. The Americans had neither. Yet, the years of war made clear the relative strengths and weaknesses of both sides.

Practice Question 2 Which of the following best describes the relative strengths and weaknesses of the British and Americans during the Revolutionary War? A. The American colonists outnumbered the British population B. The British Army and Navy were very experienced C. The American colonists lacked strong military leadership

Learning Outcomes: The Impact of the War 5.3: Describe the resolution and aftermath of the American Revolutionary War 5.3.1 Identify the main terms of the Treaty of Paris (1783) 5.3.2 Summarize short- and long-term consequences of the American Revolution 5.3.3 Explain Loyalist and Patriot sentiments and responses to the Revolutionary War 5.3.4 Describe the impact of the American Revolution on enslaved laborers and Native Americans 5.3.5 Describe the impact of the American Revolution on women

Introduction to The Impact of the War What you ll learn to do: describe the resolution and aftermath of the American Revolutionary War

The British defeat at Yorktown made the outcome of the war all but certain. In light of the American victory, the Parliament of Great Britain voted to end further military operations against the rebels and to begin peace negotiations. In April 1782, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay had begun informal peace negotiations in Paris. Officials from Great Britain and the United States finalized the treaty in 1783, signing the Treaty of Paris in September of that year. The treaty recognized the independence of the United States; placed the western, eastern, northern, and southern boundaries of the nation at the Mississippi River, the Atlantic Ocean, Canada, and Florida, respectively; and gave New Englanders fishing rights in the waters off Newfoundland. Under the terms of the treaty, individual states were encouraged to refrain from persecuting Loyalists and to return their confiscated property. The Treaty of Paris

The Impact of Revolution The American Revolution has many short- and long- term consequences. Perhaps the most important immediate consequence of declaring independence was the creation of state constitutions in 1776 and 1777. The Revolution also unleashed powerful political, social, and economic forces that would transform the new nation s politics and society, including increased participation in politics and governance, the legal institutionalization of religious toleration, and the growth and diffusion of the population, particularly westward. The Revolution affected Native Americans by opening up western settlement and creating governments hostile to their territorial claims. Even more broadly, the Revolution ended the mercantilist economy, opening new opportunities in trade and manufacturing.

Identity During the Revolution In the new United States, the Revolution largely reinforced a racial identity based on skin color. Whiteness, now a national identity, denoted freedom and stood as the key to power. Blackness, more than ever before, denoted servile status. Indeed, despite their class and ethnic differences, White revolutionaries stood mostly united in their hostility to both Blacks and Indians. For enslaved laborers willing to run away and join the British, the American Revolution offered a unique occasion to escape bondage. Of the half a million slaves in the American colonies during the Revolution, twenty thousand joined the British cause. Between 10,000-20,000 enslaved laborers gained their freedom because of the Revolution; arguably, the Revolution created the largest slave uprising and the greatest emancipation until the Civil War. After the Revolution, some of these African Loyalists emigrated to Sierra Leone on the west coast of Africa. Others removed to Canada and England.

Identity During the Revolution Powerful Native Americans who had allied themselves with the British, including the Mohawk and the Creek, also remained loyal to the Empire. After their defeat, the British did not keep their promises to help their Native American allies hold on to their territory; in fact, the Treaty of Paris granted the United States huge amounts of supposedly British-owned regions that were actually Native American lands.

Identity During the Revolution The 1783 Treaty of Paris did not address Native Americans at all. All lands held by the British east of the Mississippi and south of the Great Lakes (except Spanish Florida) now belonged to the new American republic. Though the treaty remained silent on the issue, much of the territory now included in the boundaries of the United States remained under the control of native peoples

Identity During the Revolution In colonial America, women shouldered enormous domestic and child-rearing responsibilities. The war for independence only increased their workload and, in some ways, solidified their roles. Rebel leaders required women to produce articles for war everything from clothing to foodstuffs while also keeping their homesteads going. Women were also expected to provide food and lodging for armies and to nurse wounded soldiers. The Revolution opened some new doors for women, however, as they took on public roles usually reserved for men. The Daughters of Liberty, an informal organization formed in the mid-1760s to oppose British revenue-raising measures, worked tirelessly to support the war effort.

Class Discussion How radical was the American Revolution? Was the United States founded as a Christian nation?

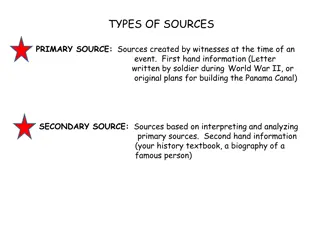

Learning Outcomes: Historical Hack: Thinking Critically About Sources 5.4: Sift, question, and interpret complex material: Use the SIFT Method to evaluate sources 5.4.1 Differentiate between reliable and unreliable and popular and scholarly sources of information 5.4.2 Identify the expertise and agenda of sources of information 5.4.3 Corroborate and trace claims in order to determine the validity of sources

Historical Hack: Thinking Critically About Sources What you ll learn to do: examine how historical accounts are understood and constructed from various perspectives and sources

Class Activity: Dive into the SIFT method activities in small groups and then come together to discuss.

Quick Review Can you analyze the events that set the stage for the American Revolution and describe its beginnings? Can you describe the British and American strategies and the key battles during the war? Can you describe the resolution and aftermath of the American Revolutionary War? Can you use the SIFT Method to evaluate sources?