Russian Formalism: An Overview of Speech Genres and Intertextuality

Russian Formalism, a literary theory movement that emerged in the early 20th century, viewed literature as a distinct form of language. It was characterized by a shift from romantic and symbolist traditions towards a focus on structural analysis and the study of literary systems. Mikhail Bakhtin, a key figure influenced by Formalism, delved into the complexities of speech genres and intertextuality. This overview explores the evolution of Formalism, its theoretical foundations, and the key principles it established for the analysis of literature.

Download Presentation

Please find below an Image/Link to download the presentation.

The content on the website is provided AS IS for your information and personal use only. It may not be sold, licensed, or shared on other websites without obtaining consent from the author. Download presentation by click this link. If you encounter any issues during the download, it is possible that the publisher has removed the file from their server.

E N D

Presentation Transcript

MKHAL BAKHTN RUSS AN FORMAL STS THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES Serkan etinkaya INTERTEXTUALITY

RUSSAN FORMALSTS A BRIEF INTRODUCTION Russian Formalists considered literature to be a special use of language. As such it was amenable to analysis in and of itself. Peter Steiner considers Russian Formalism to fall into three periods: (Everard, 2016) the mechanical view of language; the organic view literature as organism of inter-related parts; and the the systemic view literature as a system, or organising principle.

RUSSAN FORMALSTS A BRIEF INTRODUCTION Formalism began near the beginning of the 20th century, emerging in the OPOYAZ group (Society for Poetic Language) as a break with the late romantic tradition of symbolism in literature and Futurism and a number of related movements in the visual arts. In 1928 Tynyanov, with Roman Jakobson published the Theses on Language. These formed the basis for the development of structuralism.

RUSSAN FORMALSTS A BRIEF INTRODUCTION These were: (Everard, 2016) 1. Literary science had to have a firm theoretical basis and an accurate terminology. 2. The structural laws of a specific field of literature had to be established before it was related to other fields. 3. The evolution of literature must be studied as a system. All evidence, whether literary or non- literary must be analysed functionally. 4. The distinction between synchrony and diachrony was useful for the study of literature as for language, uncovering systems at each separate stage of development. But the history of systems is also a system; each synchronic system has its own past and future as part of its structure. Therefore the distinction should not be preserved beyond its usefulness.

RUSSAN FORMALSTS A BRIEF INTRODUCTION 5. A synchronic system is not a mere agglomerate of contemporaneous phenomena catalogued. Systems means hierarchical organisation. The distinction between langue and parole, taken from linguistics, deserves to be developed for literature in order to reveal the principles underlying the relationship between the individual utterance and a prevailing complex of norms. The analysis of the structural laws of literature should lead to the setting up of a limited number of structural types and evolutionary laws governing those types. The discovery of the immanant laws of a genre allows one to describe an evolutionary step, but not to explain why this step has been taken by literature and not another. Here the literary must be related to the relevant non-literary facts to find further laws, a system of systems . But still the immanent laws of the individual work had to be enunciated first. 6. 7. 8.

MIKHAIL BAKHTIN AND RUSSIAN FORMALISM Mikhail Bakhtin, WAS influenced by if not directly linked with the Russian Formalists. His contributions to the notion of dialogism and the notion of voice in literary discourse emerged contemporaneously with considerations of sound and rhythmic elements in Formalist analyses. In other directions, the Bakhtin School combined elements of Formalism with Marxism. It was formalist insofar as it was concerned with the linguistic structure of literary texts, but was marxist in its comitment to the view that language could not be separated from ideology. At the same time it resisted the purely marxist turn insofar as it resisted the view that language arose as a reflex of a material socio-economic substructure. (Everard, 2016)

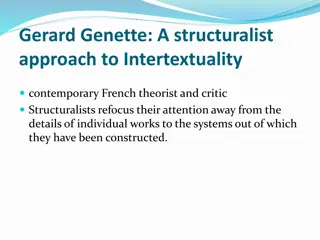

MIKHAIL BAKHTIN AND RUSSIAN FORMALISM It is viable to cite the Russian literary theorist M. M. Bakhtin as the originator, if not of the term intertextuality , then at least of the specific view of language which helped others articulate theories of intertextuality. Bakhtin, as we will see, takes a verydifferent approach to language and is far more concerned than Saussure with the social contexts within which words are exchanged. If the relational nature of the word for Saussure stems from a vision of language seen as a generalized and abstract system, for Bakhtin it stems from the word s existence within specific social sites, specific social registers and specific moments of utterance and reception. Since neither Saussure nor Bakhtin actually employs the term, most people would wish to credit Julia Kristeva with being the inventor of intertextuality . Kristeva, as we shall observe, is influenced by both Bakhtinian and Saussurean models and attempts to combine their insights and major theories. (Allen, 2000: 11)

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 The Saussurean linguistics and language as a living dialogue (translinguistics). In a relatively short space, this essay takes up a topic about which Bakhtin had planned to write a book, making the essay a rather dense and complex read. It is here that Bakhtin distinguishes between literary and everyday language. According to Bakhtin, genres exist not merely in language, but rather in communication. In dealing with genres, Bakhtin indicates that they have been studied only within the realm of rhetoric and literature, but each discipline draws largely on genres that exist outside both rhetoric and literature. These extraliterary genres have remained largely unexplored. Bakhtin makes the distinction between primary genres and secondary genres, whereby primary genres legislate those words, phrases, and expressions that are acceptable in everyday life, and secondary genres are characterized by various types of text such as legal, scientific, etc. (Holquist, 1990: XV) Problem of Speech Genres deals with the difference between

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 Here, Bakhtin begins by noting that human activity is inextricably related to the use of language , the nature and forms of which are just as diverse as are the areas of human activity (Bakhtin, 1986:81), this notwithstanding the national unity of language (Bakhtin, 1986:60). Language is, Bakhtin argues, realised in the form of individual concrete utterances (oral and written) by participants in the various areas of human activity . These specific conditions and goals of each such area not only though their content (thematic) and linguistic style, that is, the selection of the lexical, phraseological, and grammatical resources of the language, but above all through their compositional structure (Bakhtin, 1986:60). utterances reflect the The thematic content, style, and compositional structure are inseparably linked to the whole of the utterance and are determined by the specific nature of the particular sphere of communication . Bakhtin s point is that each sphere in which language is used develops its own relatively stable types if these utterances which he terms speech genres (Bakhtin, 1986:60).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 Bakhtin emphasises the extreme heterogeneity of speech genres (oral and written) (Bakhtin, including short rejoinders of daily dialogue which vary according situation, and participants , the brief standard military command, the elaborate and detailled order, the fairly variegated repertoire of business commentary (in the broad sense of the word: social, political (Bakhtin, 1986:60), and the diverse forms of scientific statements and all literary genres (from multivolume novel) (Bakhtin, 1986:61). to subject, matter, documents, . . . the diverse world of the proverb to the Though [l]iterary genres , rhetorical genres and everyday speech genres (Bakhtin, have all been the focus of study, the general linguistic problem of the utterance and its types have hardly been considered at all (Bakhtin, 1986:61).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 Bakhtin distinguishes between primary (simple) and secondary (complex) speech genres (Bakhtin, 1986:61). The latter includes novels, dramas, all kinds of scientific research, major genres of commentary which arise in more complex and comparatively highly developed and organised cultural communication (primarily written) which, in the process of their formation, . . . absorb and digest various primary (simple) genres which in turn are altered and assume a special character when they enter into complex ones , thereby losing their immediate relation to actual reality and to the real utterances of others (Bakhtin, 1986:62). According to Bakhtin, style is inseparably related to the utterance and to typical forms of utterances, that is, speech genres . Some genres (e.g. those of artistic literature ) are more conducive to reflecting the individuality of the speaker in the language of the utterance, that is, to an individual style than others ( business documents, military commands, verbal signals in industry, and so on ) (Bakhtin, 1986:63).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 To offer a historical explanation of the complex historical dynamics of these styles, one must develop a special history of speech genres . . . that reflects . . . all the changes taking place in social life . Utterances and their types, that is, speech genres, are the drive belts from the history of society to the history of language (Bakhtin, 1986:65). All in all, any utterance is a union of grammar and lexicon (drawn from the language system ) and stylistics (of the individual utterance). Grammar and stylistics converge and diverge in any concrete language phenomenon in which, as a result, they are organically combined (Bakhtin, 1986:66). Bakhtin contends that the study of the utterance as a real unit of speech communication will also make it possible to understand more correctly the nature of language units (as a system): words and sentences (Bakhtin, 1986:67).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 At this point, Bakhtin is of the view that nineteenth century linguistics, epitomised by Wilhelm von Humboldt, downplayed the communicative function of language in order to emphasise thought emerging independently of communication . His successors, such as the Vosslerians, emphasise the expressive function of language which boils down to the expression of the speaker s individual discourse : [l]anguage arises from man s need to express himself, to objectify himself. The essence of any form of language is somehow reduced to the spiritual creativity of the individuum (Bakhtin, 1986:67). From this perspective, language is viewed as if there were only one speaker who does not have any necessary relation to other participants in speech communication. If the role of the other is taken into account at all, it is the role of a listener, who understands the speaker only passively. . . . Language essentially needs only . . . one speaker . . . and an object for his speech (Bakhtin, 1986:67), the communication function of language being secondary. In this schema, the language collective, the plurality of speakers , viewed as a kind of collective personality, the spirit of the people is often extolled but in fact denied any real essential significance (Bakhtin, 1986:68).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 The speaker does not expect passive understanding that . . . only duplicates his own idea in someone else s mind. Rather, he expects response, agreement, sympathy, objection, execution, and so forth . Moreover, each speaker is himself a respondent for he is not, after all, the first speaker, the one disturbs the eternal silence of the universe . He presupposes not only the existence of the language system he is using, but also the existence of preceding utterances his own and others with which his given utterance enters into one kind of relation or another (builds on them, polemicises with them, or simply presumes that they are already known to the listener) (Bakhtin, 1986:69) Bakhtin argues that the boundaries of each concrete utterance as a unit of speech communication are determined by a change of speaking subjects (Bakhtin, 1986:71). Whether a short rejoinder or a novel or a scientific treatise, each utterance has an absolute beginning and an absolute end: its beginning is preceded by the utterances of others, and its end is followed by the responsive utterances of others (Bakhtin, 1986:71), or others active responsive understanding (Bakhtin, 1986:71) or a responsive action based on this understanding (Bakhtin, 1986:71).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 Dialogue is a classic form of speech communication . Each rejoinder has a specific quality of completion that expresses a particular position of the speaker . Bakhtin contends that the relationships by which rejoinders are all linked to each other (take many forms (e.g. relations between question and answer, assertion and objection, assertion and agreement, suggestion and acceptance, order and execution etc.) is different from those among units of language (words and sentences), either in the system of language (in the vertical cross section) or within the utterance (on the horizontal plane) Indeed, the relations between particular rejoinders are only subcategories of specific relations among whole utterances in the process of speech communication (Bakhtin, 1986:72).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 Sometimes a sentence can serve as an utterance if there is a change of speech subjects at the end thereof but generally it is not demarcated on either side by a change of speaking subjects; it has neither direct contact with reality (with an extraverbal situation) nor a direct relationship to others utterances; it does not have a semantic fullness of value; and it has no capacity to determine directly the responsive position of the other speaker (Bakhtin, 1986:74). As a language unit, the sentence is grammatical in nature. It has grammatical boundaries and grammatical completedness and unity (Bakhtin, 1986:74). One exchanges not sentences, words or phrases but utterances constructed out of these language units.

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 This finalised wholeness of the utterance, guaranteeing the possibility of response (or of responsive understanding) is determined by three aspects . . . inseparably linked in the organic whole of the utterance: (Bakhtin, 1986:77) 1. semantic exhaustiveness of the theme; 2. the speaker s plan or speech will; 3. typical compositional and generic forms of finalisation . The first refers to attribution of reference, what the discourse is ostensibly about, the sense had by the listener that the speaker has said everything he can about a particular subject.

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 The second refers to the attribution of intention, that is, how we imagine to ourselves what the speaker wishes to say . This is the subjective aspect of the utterance which combines in an inseparable unity with the objective referentially semantic aspect , limiting the latter by relating it to a concrete (individual) situation of speech communication with all its individual circumstances, its personal participants, and the statement-utterances which preceded it (Bakhtin, 1986:77). Bakhtin then turns his attention to the third and most important aspect: the stable generic forms which necessarily inform each speech act. The speaker s speech will is manifested in the choice of a particular speech genre which is determined by the specific nature of the given sphere of speech communication, semantic (thematic) considerations, the concrete situation of the speech communication, the personal composition of its participants, etc. (Bakhtin, 1986:78).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 We absorb our native language its lexical composition and grammatical structure not from dictionaries and grammars but from concrete utterances that we hear and that we ourselves reproduce in live speech communication with people around us . The forms of language and the typical forms of utterances, that is, speech genres, enter our experience and our consciousness together, and in close connection with each other . To learn to speak means to learn to construct utterances (because we speak in utterances and not in individual sentences, and, of course, not in individual words (Bakhtin, 1986:78) as a result of which speech genres organise our speech in almost the same way as grammatical (syntactical) forms do (Bakhtin, 1986:78-79).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 When we hear others speak, we guess its genre from the very first words; we predict a certain length . . . and a certain compositional structure; we foresee the end; that is, from the very beginning we have a sense of the speech whole (Bakhtin, 1986:79). The sentence as a unit of language, like the word, has no author. . . . [I]t belongs to nobody, and only by functioning as a whole utterance does become an expression of the position of someone speaking individually in a concrete situation of speech communication (Bakhtin, 1986:84). This leads Bakhtin to speculate on the three characteristics which distinguish any utterance.

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 The first aspect of the utterance that determines its compositional and stylistic features is its particular referentially semantic content . In other words, each utterance makes a claim of some kind about reality. The second aspect is the expressive aspect, that is, the speaker s subjective emotional evaluation of the referentially semantic content of his utterance . This emotional component may vary but can never be totally absent for there is no such thing as an absolutely neutral utterance . The third feature of the utterance is its relation to the speaker himself (the author of the utterance) and to the other participants in speech communication (Bakhtin, 1986:84).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 Every utterance must be regarded as a response to preceding utterances of the given sphere. . . . Each utterance refutes, affirms, supplements, and relies on the others, presupposes them to be known, and somehow takes them into account. After all, as regards a given question, in a given matter, and so forth, the utterance occupies a particular definite position in a given sphere of communication. It is impossible to determine its position without correlating it with other positions. Bakhtin stresses that the utterance is related not only to preceding but also to subsequent links in the chain of speech communication (Bakhtin, 1986:94).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 Tradition stylistics focuses on the semantic and thematic content (Bakhtin, 1986:97) and the speaker s expressive attitude (Bakhtin, 1986:97), ignoring the constitutive role of the audience. The question of the addressee is of immense significance in literary history. Each epoch, each literary trend and literary-artistic style, each literary genre within an epoch or trend, is typified by its own special concepts of the addressee of the literary work (Bakhtin, 1986:98).

THE PROBLEM OF SPEECH GENRES / 1986 All in all, addressivity, the quality of turning to someone, is a constitutive feature of the utterance, without it the utterance does not and cannot exist . Language units such as the word or sentence lack this quality for they belong to nobody and are addressed to nobody . Such units acquire addressivity only in the whole of a concrete utterance . By contrast, utterances are imbued with traces of addressivity and the influence of the anticipated response, dialogical echoes form others preceding utterances, faint traces of changes of speech subjects that have furrowed the utterance from within (Bakhtin, 1986:99).

REFERENCES Allen, G. (2000). Intertextuality. London: Routledge. Bakhtin, M., Holquist, M., McGee, V., & Emerson, C. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. Austin: University of Texas Press. Clarke, R. (2016). LITS3304 POST-STRUCTURALISMS AND POST-COLONIALISMS. Rlwclarke.net. Retrieved 25 February 2016, from http://www.rlwclarke.net/courses/LITS3304/2010- 2011/03ABakhtin,TheProblemofSpeechGenres.pdf Everard, J. (2016). Mindsigh Russian Formalism. Lostbiro.com. Retrieved 25 February 2016, from http://lostbiro.com/blog/?page_id=524%3E%3Cmeta%20http-equiv= Holquist, M. (1990). Dialogism. London: Routledge.